World population

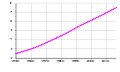

In world demographics, the world population is the total number of humans currently living. It was estimated by the United Nations to have exceeded eight billion in mid-November 2022. It took around 300,000 years of human prehistory and history for the human population to reach a billion and only 218 years more to reach 8 billion.

The human population has experienced continuous growth following the Great Famine of 1315–1317 and the end of the Black Death in 1350, when it was nearly 370,000,000.[2] The highest global population growth rates, with increases of over 1.8% per year, occurred between 1955 and 1975, peaking at 2.1% between 1965 and 1970.[3] The growth rate declined to 1.1% between 2015 and 2020 and is projected to decline further in the 21st century.[4] The global population is still increasing, but there is significant uncertainty about its long-term trajectory due to changing fertility and mortality rates.[5] The UN Department of Economics and Social Affairs projects between 9 and 10 billion people by 2050 and gives an 80% confidence interval of 10–12 billion by the end of the 21st century,[1] with a growth rate by then of zero. Other demographers predict that the human population will begin to decline in the second half of the 21st century.[6]

The total number of births globally is currently (2015–2020) 140 million/year, which is projected to peak during the period 2040–2045 at 141 million/year and then decline slowly to 126 million/year by 2100.[7] The total number of deaths is currently 57 million/year and is projected to grow steadily to 121 million/year by 2100.[8]

The median age of human beings as of 2020 is 31 years.[9]

Human population as a function of food availability

Individuals from a wide range of academic fields and political backgrounds have proposed that, like all other animal populations, any human population (and, by extension, the world population) predictably grows and shrinks according to available food supply, growing during an abundance of food and shrinking in times of scarcity.[153] This idea may run counter to the popular thinking that, as population grows, food supply must also be increased to support the growing population; instead, the claim here is that growing population is the result of a growing food supply. Notable proponents of this notion include: agronomist and insect ecologist David Pimentel,[154] behavioral scientist Russell Hopfenberg (the former two publishing a study on the topic in 2001),[155] anthropologist and activist Virginia Abernethy,[156] ecologist Garrett Hardin,[157] science writer and anthropologist Peter Farb, journalist Richard Manning,[158] environmental biologist Alan D. Thornhill,[159] cultural critic and writer Daniel Quinn,[160] and anarcho-primitivist John Zerzan.[161]

Scientists generally acknowledge that at least one significant factor contributing to population growth (or overpopulation) is that as agriculture advances in creating more food, the population consequently increases—the Neolithic Revolution and Green Revolution often specifically provided as examples of such agricultural breakthroughs.[162][163][164][165][166][167] Furthermore, certain scientific studies do lend evidence to food availability in particular being the dominant factor within a more recent timeframe.[168][169][154] Other studies take it as a basic model from which to make broad population conjectures.[162] The idea became taboo following the United Nations' 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, where framing human population growth as negatively impacting the natural environment became regarded as "anti-human".[170]

Most human populations throughout history validate this theory, as does the overall current global population. Populations of hunter-gatherers fluctuate in accordance with the amount of available food. The world human population began consistently and sharply to rise, and continues to do so, after sedentary agricultural lifestyles became common due to the Neolithic Revolution and its increased food supply.[171][164][167] This was, subsequent to the Green Revolution starting in the 1940s, followed by even more severely accelerated population growth. Often, wealthier countries send their surplus food resources to the aid of starving communities; however, some proponents of this theory argue that this seemingly beneficial strategy only results in further harm to those communities in the long run. Anthropologist Peter Farb, for example, has commented on the paradox that "intensification of production to feed an increased population leads to a still greater increase in population."[172] Environmental writer Daniel Quinn has also focused on this phenomenon, which he calls the "food race", coining a term he felt was comparable, in terms of both escalation and potential catastrophe, to the nuclear arms race.

Criticism of this theory can come from multiple angles, for example by demonstrating that human population is not solely an effect of food availability, but that the situation is more complex. For instance, other relevant factors that can increase or limit human population include fresh water availability, arable land availability, energy consumed per person, heat removal, forest products, and various nonrenewable resources like fertilizers.[173] Another criticism is that, in the modern era, birth rates are lowest in the developed nations, which also have the highest access to food. In fact, some developed countries have both a diminishing population and an abundant food supply. The United Nations projects that the population of 51 countries or areas, including Germany, Italy, Japan, and most of the states of the former Soviet Union, is expected to be lower in 2050 than in 2005.[174] This shows that, limited to the scope of the population living within a single given political boundary, particular human populations do not always grow to match the available food supply. However, the global population as a whole still grows in accordance with the total food supply and many of these wealthier countries are major exporters of food to poorer populations, so that, according to Hopfenberg and Pimentel's 2001 research, "it is through exports from food-rich to food-poor areas... that the population growth in these food-poor areas is further fueled.[154] Their study thus suggests that human population growth is an exacerbating feedback loop in which food availability creates a growing population, which then causes the misimpression that food production must be consequently expanded even further.[175]

Regardless of criticisms against the theory that population is a function of food availability, the human population is, on the global scale, undeniably increasing,[176] as is the net quantity of human food produced—a pattern that has been true for roughly 10,000 years, since the human development of agriculture. The fact that some affluent countries demonstrate negative population growth fails to discredit the theory as a whole, since the world has become a globalized system with food moving across national borders from areas of abundance to areas of scarcity. Hopfenberg and Pimentel's 2001 findings support both this[154] and Daniel Quinn's direct accusation, in the early 2010s, that "First World farmers are fueling the Third World population explosion".[177]

Organizations

Statistics and maps

Population clocks