Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution, also known as the First Agricultural Revolution, was the wide-scale transition of many human cultures during the Neolithic period in Afro-Eurasia from a lifestyle of hunting and gathering to one of agriculture and settlement, making an increasingly large population possible.[1] These settled communities permitted humans to observe and experiment with plants, learning how they grew and developed.[2] This new knowledge led to the domestication of plants into crops.[2][3]

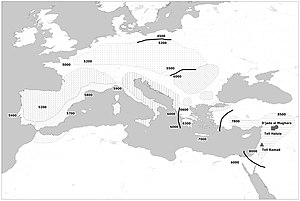

Archaeological data indicates that the domestication of various types of plants and animals happened in separate locations worldwide, starting in the geological epoch of the Holocene 11,700 years ago, after the end of the last Ice Age.[4] It was the world's first historically verifiable transition to agriculture. The Neolithic Revolution greatly narrowed the diversity of foods available, resulting in a decrease in the quality of human nutrition compared with that obtained previously from foraging,[5][6][7] but because food production became more efficient, it released humans to invest their efforts in other activities and was thus "ultimately necessary to the rise of modern civilization by creating the foundation for the later process of industrialization and sustained economic growth".[8]

The Neolithic Revolution involved much more than the adoption of a limited set of food-producing techniques. During the next millennia, it transformed the small and mobile groups of hunter-gatherers that had hitherto dominated human pre-history into sedentary (non-nomadic) societies based in built-up villages and towns. These societies radically modified their natural environment by means of specialized food-crop cultivation, with activities such as irrigation and deforestation which allowed the production of surplus food. Other developments that are found very widely during this era are the domestication of animals, pottery, polished stone tools, and rectangular houses. In many regions, the adoption of agriculture by prehistoric societies caused episodes of rapid population growth, a phenomenon known as the Neolithic demographic transition.

These developments, sometimes called the Neolithic package,[9] provided the basis for centralized administrations and political structures, hierarchical ideologies,[10] depersonalized systems of knowledge (e.g. writing), densely populated settlements, specialization and division of labour, more trade, the development of non-portable art and architecture, and greater property ownership.[11] The earliest known civilization developed in Sumer in southern Mesopotamia (c. 6,500 BP); its emergence also heralded the beginning of the Bronze Age.[12]

The relationship of the aforementioned Neolithic characteristics to the onset of agriculture, their sequence of emergence, and their empirical relation to each other at various Neolithic sites remains the subject of academic debate. It is usually understood to vary from place to place, rather than being the outcome of universal laws of social evolution.[13][14]

Background[edit]

Hunter-gatherers had different subsistence requirements and lifestyles from agriculturalists. Hunter-gatherers were often highly mobile and migratory, living in temporary shelters and in small tribal groups, and having limited contact with outsiders. Their diet was well-balanced though heavily dependent on what the environment could provide each season. In contrast, because the surplus and plannable supply of food provided by agriculture made it possible to support larger population groups, agriculturalists lived in more permanent dwellings in more densely populated settlements than what could be supported by a hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The agricultural communities' seasonal need to plan and coordinate resource and manpower encouraged division of labour, which gradually led to specialization of labourers and complex societies. The subsequent development of trading networks to exchange surplus commodities and services brought agriculturalists into contact with outside groups, which promoted cultural exchanges that led to the rise of civilizations and technological evolutions.[15]

However, population increase and food abundance did not necessarily correlate with improved health. Reliance on a very limited variety of staple crops can adversely affect health even while making it possible to feed more people. Maize is deficient in certain essential amino acids (lysine and tryptophan) and is a poor source of iron. The phytic acid it contains may inhibit nutrient absorption. Other factors that likely affected the health of early agriculturalists and their domesticated livestock would have been increased numbers of parasites and disease-bearing pests associated with human waste and contaminated food and water supplies. Fertilizers and irrigation may have increased crop yields but also would have promoted proliferation of insects and bacteria in the local environment while grain storage attracted additional insects and rodents.[15]

The term 'neolithic revolution' was invented by V. Gordon Childe in his book Man Makes Himself (1936).[18][19] Childe introduced it as the first in a series of agricultural revolutions in Middle Eastern history,[20] calling it a "revolution" to denote its significance, the degree of change to communities adopting and refining agricultural practices.[21]

The beginning of this process in different regions has been dated from 10,000 to 8,000 BCE in the Fertile Crescent,[22][23] and perhaps 8000 BCE in the Kuk Early Agricultural Site of Papua New Guinea in Melanesia.[24][25] Everywhere, this transition is associated with a change from a largely nomadic hunter-gatherer way of life to a more settled, agrarian one, with the domestication of various plant and animal species – depending on the species locally available, and influenced by local culture. Recent archaeological research suggests that in some regions, such as the Southeast Asian peninsula, the transition from hunter-gatherer to agriculturalist was not linear, but region-specific.[26]

The most prominent of several theories (not mutually exclusive) as to factors that caused populations to develop agriculture include: