Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (Russian: Иван IV Васильевич;[d] 25 August 1530 – 28 March [O.S. 18 March] 1584), commonly known as Ivan the Terrible,[note 1] was Grand Prince of Moscow and all Russia from 1533 to 1547, and the first Tsar and Grand Prince of all Russia from 1547 until his death in 1584.[4]

"Ivan IV" and "Ivan Grozny" redirect here. For the grand prince of Ryazan, see Ivan IV of Ryazan. For the volcano, see Grozny Group. For other uses, see Ivan the Terrible (disambiguation).

Ivan IV

Иван IV

26 January 1547 – 28 March 1584[a]

26 January 1547[b]

Himself as Grand Prince of all Russia

13 December 1533 – 26 January 1547[c]

Himself as Tsar of all Russia

Elena Glinskaya (1533–1538)

25 August [O.S. 15 August] 1530

Kolomenskoye

Ivan IV was the eldest son of Vasili III by his second wife Elena Glinskaya, and a grandson of Ivan III and Sophia Palaiologina. He succeeded his father after his death, when he was three years old. A group of reformers united around the young Ivan, crowning him as tsar in 1547 at the age of 16. Ivan's reign was characterised by Russia's transformation from a medieval state to an empire under a tsar, but at an immense cost to its people and long-term economy.

In the early years of his reign, Ivan ruled with the group of reformers known as the Chosen Council and established the Zemsky Sobor, a new assembly convened by the tsar. He also revised the legal code and introduced reforms, including elements of local self-government, as well as establishing the first Russian standing army, the streltsy. Ivan conquered the khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan, and significantly expanded the territory of Russia.

After he had consolidated his power, Ivan rid himself of the advisers from the Chosen Council and triggered the Livonian War, which ravaged Russia and resulted in failure to take control over Livonia and the loss of Ingria, but allowed him to establish greater autocratic control over the Russian nobility, which he violently purged using Russia's first political police, the oprichniki. The later years of Ivan's reign were marked by the massacre of Novgorod and the burning of Moscow by the Tatars.

Ivan pursued cultural improvements, such as importing the first printing press to Russia. He also began several processes that would continue for centuries, including deepening connections with other European states, particularly England, fighting wars against the Ottoman Empire, and the gradual conquest of Siberia.

Contemporary sources present disparate accounts of Ivan's complex personality. He was described as intelligent and devout, but also prone to paranoia, rage, and episodic outbreaks of mental instability that worsened with age.[5][6][7] Historians generally believe that in a fit of anger, he murdered his eldest son and heir, Ivan Ivanovich;[8] he might also have caused the miscarriage of the latter's unborn child. This left his younger son, the politically ineffectual Feodor Ivanovich, to inherit the throne, a man whose rule and subsequent childless death led directly to the end of the Rurik dynasty and the beginning of the Time of Troubles.

Nickname[edit]

The English word terrible is usually used to translate the Russian word грозный (grozny) in Ivan's epithet, but this is a somewhat archaic translation. The Russian word грозный reflects the older English usage of terrible as in "inspiring fear or terror; dangerous; powerful" (i.e., similar to modern English terrifying). It does not convey the more modern connotations of English terrible such as "defective" or "evil".[9] According to Edward L. Keenan, Ivan the Terrible's image in popular culture as a tyrant came from politicised Western travel literature of the Renaissance era.[10] Anti-Russian propaganda during the Livonian War portrayed Ivan as a sadistic and oriental despot.[4] Vladimir Dal defines grozny specifically in archaic usage and as an epithet for tsars: "courageous, magnificent, magisterial and keeping enemies in fear, but people in obedience".[11] Other translations have also been suggested by modern scholars, including formidable,[12][13][14] as well as awe-inspiring.[4]

Ivan's notorious outbursts and autocratic whims helped characterise the position of tsar as one accountable to no earthly authority but only to God.[28] Tsarist absolutism faced few serious challenges until the 19th century. The earliest and most influential account of his reign prior to 1917 was by the historian N.M. Karamzin, who described Ivan as a 'tormentor' of his people, particularly from 1560, though even after that date Karamzin believed there was a mix of 'good' and 'evil' in his character. In 1922, the historian Robert Wipper - who later returned to his native Latvia to avoid living under communist rule - wrote a biography that reassessed Ivan as a monarch "who loved the ordinary people" and praised his agrarian reforms.[101]

In the 1920s, Mikhail Pokrovsky, who dominated the study of history in the Soviet Union, attributed the success of the oprichnina to their being on the side of the small state owners and townsfolk in a decades-long class struggle against the large landowners, and downgraded Ivan's role to that of the instrument of the emerging Russian bourgeoisie. But in February 1941, the poet Boris Pasternak observantly remarked in a letter to his cousin that "the new cult, openly proselytized, is Ivan the Terrible, the Oprichnina, the brutality."[102] Joseph Stalin, who had read Wipper's biography had decided that Soviet historians should praise the role of strong leaders, such as Ivan, Alexander Nevsky and Peter the Great, who had strengthened and expanded Russia.[103] In post-Soviet Russia, a campaign has been run to seek the granting of sainthood to Ivan IV,[104] but the Russian Orthodox Church opposed the idea.[105]

A consequence was that the writer Alexei Tolstoy began work on a stage version of Ivan's life, and Sergei Eisenstein began what was to be a three part film tribute to Ivan. Both projects were personally supervised by Stalin, at a time when the Soviet Union was engaged in a war with Nazi Germany. He read the scripts of Tolstoy's play and the first of Eisenstein's films in tandem after the Battle of Kursk in 1943, praised Eisenstein's version but rejected Tolstoy's. It took Tolstoy until 1944 to write a version that satisfied the dictator.[106] Eisenstein's success with Ivan the Terrible Part 1 was not repeated with the follow-up, The Boyar's Revolt, which angered Stalin because it portrayed a man suffering pangs of conscience. Stalin told Eisenstein: "Ivan the Terrible was very cruel. You can show that he was cruel, but you have to show why it was essential to be cruel. One of Ivan the Terrible's mistakes was that he didn't finish off the five major families."[107] The film was suppressed until 1958.

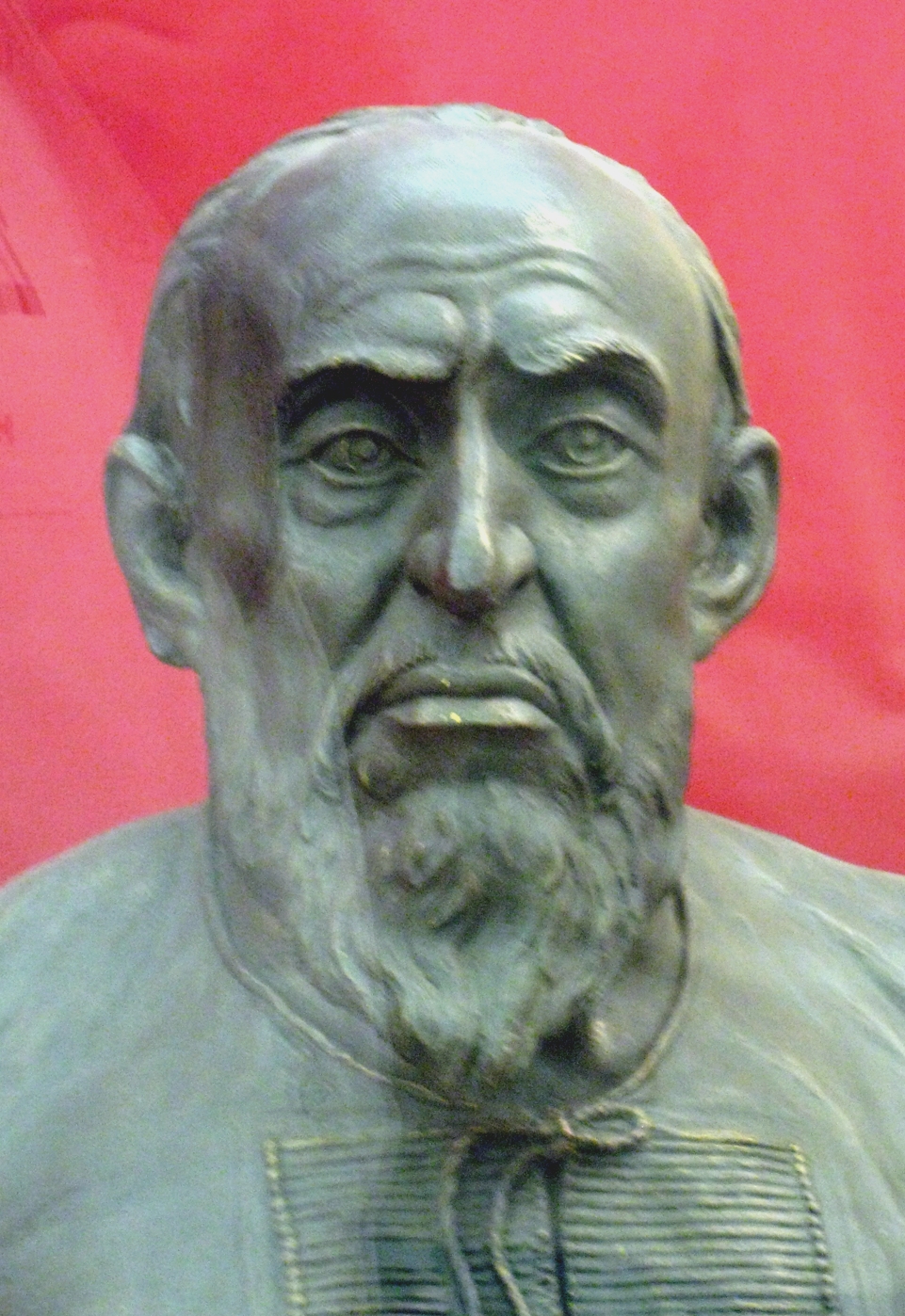

The first statue of Ivan the Terrible was officially open in Oryol, Russia, in 2016. Formally, the statue was unveiled in honor of the 450th anniversary of the founding of Oryol, a Russian city of about 310,000 that was established as a fortress to defend Moscow's southern borders. Informally, there was a big political subtext. The opposition thinks that Ivan the Terrible's rehabilitation echoes of Stalin's era. The erection of the statue was vastly covered in international media like The Guardian,[108] The Washington Post,[109] Politico,[110] and others. The Russian Orthodox Church officially supported the erection of the monument.[111]