Japanese war crimes

During its imperial era, the Empire of Japan committed numerous war crimes and crimes against humanity across various Asian-Pacific nations, notably during the Second Sino-Japanese and Pacific Wars. These incidents have been referred to as "the Asian Holocaust",[3][4] and as "Japan's Holocaust".[5] The crimes occurred during the early part of the Shōwa era, under Hirohito's reign.

Japanese war crimes

In and around East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific

1927–1945[1]

war crimes, mass murder, and other crimes against humanity

c. 30,000,000[2]

Tokyo Trial, and others

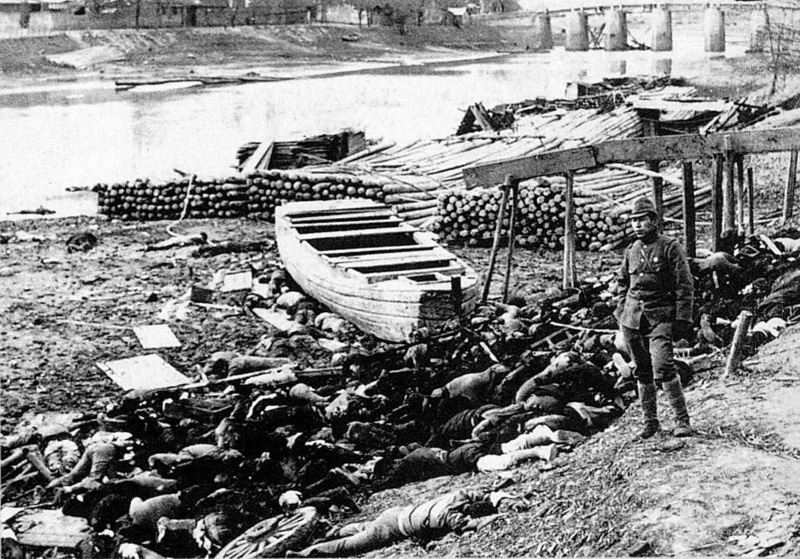

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) were responsible for a multitude of war crimes leading to millions of deaths. War crimes ranged from sexual slavery and massacres to human experimentation, starvation, and forced labor, all either directly committed or condoned by the Japanese military and government.[6][7][8][9][10] Evidence of these crimes, including oral testimonies and written records such as diaries and war journals, has been provided by Japanese veterans.[11]

The Japanese political and military leadership knew of its military's crimes, yet continued to allow it and even support it, with the majority of Japanese troops stationed in Asia either taking part in or supporting the killings.[12]

The Imperial Japanese Army Air Service participated in chemical and biological attacks on civilians during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II, violating international agreements that Japan had previously signed, including the Hague Conventions, which prohibited the use of "poison or poisoned weapons" in warfare.[13][14]

Since the 1950s, numerous apologies for the war crimes have been issued by senior Japanese government officials. Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs has acknowledged the country's role in causing "tremendous damage and suffering" during World War II, particularly the massacre and rape of civilians in Nanjing by the IJA.[15] However, the issue remains controversial, with some members of the Japanese government, including former prime ministers Junichiro Koizumi and Shinzō Abe, having paid respects at the Yasukuni Shrine, which honors all Japanese war dead, including convicted Class A war criminals. Furthermore, some Japanese history textbooks provide only brief references to the war crimes,[16] and certain members of the Liberal Democratic Party have denied some of the atrocities, such as the government's involvement in abducting women to serve as "comfort women", a euphemism for sex slaves.[17][18]

Post-war events and reactions[edit]

The parole-for-war-criminals movement[edit]

In 1950, after most Allied war crimes trials had ended, thousands of convicted war criminals sat in prisons across Asia and across Europe, detained in the countries where they were convicted. Some executions were still outstanding as many Allied courts agreed to reexamine their verdicts, reducing sentences in some cases and instituting a system of parole, but without relinquishing control over the fate of the imprisoned (even after Japan had regained its status as a sovereign country).

An intense and broadly supported campaign for amnesty for all imprisoned war criminals ensued (more aggressively in Germany than in Japan at first), as attention turned away from the top wartime leaders and towards the majority of "ordinary" war criminals (Class B/C in Japan), and the issue of criminal responsibility was reframed as a humanitarian problem.

The British authorities lacked the resources and will to fully commit themselves to pursuing Japanese war criminals.[58]

On 7 March 1950, MacArthur issued a directive that reduced the sentences by one-third for good behavior and authorized the parole of those who had received life sentences after fifteen years. Several of those who were imprisoned were released earlier on parole due to ill-health.

The Japanese popular reaction to the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal found expression in demands for the mitigation of the sentences of war criminals and agitation for parole. Shortly after the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect in April 1952, a movement demanding the release of B- and C-class war criminals began, emphasizing the "unfairness of the war crimes tribunals" and the "misery and hardship of the families of war criminals". The movement quickly garnered the support of more than ten million Japanese. In the face of this surge of public opinion, the government commented that "public sentiment in our country is that the war criminals are not criminals. Rather, they gather great sympathy as victims of the war, and the number of people concerned about the war crimes tribunal system itself is steadily increasing."

The parole-for-war-criminals movement was driven by two groups: those from outside who had "a sense of pity" for the prisoners; and the war criminals themselves who called for their own release as part of an anti-war peace movement. The movement that arose out of "a sense of pity" demanded "just set them free (tonikaku shakuho o) regardless of how it is done".

On 4 September 1952, President Truman issued Executive Order 10393, establishing a Clemency and Parole Board for War Criminals to advise the President with respect to recommendations by the Government of Japan for clemency, reduction of sentence, or parole, with respect to sentences imposed on Japanese war criminals by military tribunals.[340]

On 26 May 1954, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles rejected a proposed amnesty for the imprisoned war criminals but instead agreed to "change the ground rules" by reducing the period required for eligibility for parole from 15 years to 10.[341]

By the end of 1958, all Japanese war criminals, including A-, B- and C-class were released from prison and politically rehabilitated. Kingorō Hashimoto, Shunroku Hata, Jirō Minami and Oka Takazumi were all released on parole in 1954. Sadao Araki, Kiichirō Hiranuma, Naoki Hoshino, Okinori Kaya, Kōichi Kido, Hiroshi Ōshima, Shigetarō Shimada and Teiichi Suzuki were released on parole in 1955. Satō Kenryō, whom many, including Judge B.V.A. Röling regarded as one of the convicted war criminals least deserving of imprisonment, was not granted parole until March 1956, the last of the Class A Japanese war criminals to be released. On 7 April 1957, the Japanese government announced that, with the concurrence of a majority of the powers represented on the tribunal, the last ten major Japanese war criminals who had previously been paroled were granted clemency and were to be regarded henceforth as unconditionally free from the terms of their parole.