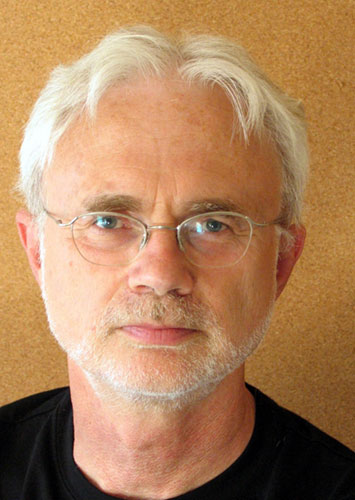

John Adams (composer)

John Coolidge Adams (born February 15, 1947) is an American composer and conductor whose music is rooted in minimalism. Among the most regularly performed composers of contemporary classical music, he is particularly noted for his operas, which are often centered around recent historical events.[1][2] Apart from opera, his oeuvre includes orchestral, concertante, vocal, choral, chamber, electroacoustic and piano music.

Not to be confused with John Luther Adams or John Clement Adams.

John Adams

February 15, 1947

- Composer

- conductor

- Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition (1995)

- Pulitzer Prize for Music (2003)

- Erasmus Prize (2019)

Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, Adams grew up in a musical family, being regularly exposed to classical music, jazz, musical theatre and rock music. He attended Harvard University, studying with Kirchner, Sessions and Del Tredici among others. Though his earliest work was aligned with modernist music, he began to disagree with its tenets upon reading John Cage's Silence: Lectures and Writings. Teaching at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, Adams developed his own minimalist aesthetic, which was first fully realized in Phrygian Gates (1977) and later in the string septet Shaker Loops. Increasingly active in the contemporary music scene of San Francisco, his large-scale orchestral works Harmonium and Harmonielehre (1985) first gained him national attention.[3] Other popular works from this time include the fanfare Short Ride in a Fast Machine (1986) and the orchestral work El Dorado (1991).[4]

Adams's first opera was Nixon in China (1987), which recounts Richard Nixon's 1972 visit to China and was the first of many collaborations with theatre director Peter Sellars. Though the work's reception was initially mixed, it has become increasingly favored since its premiere, receiving performances worldwide. Begun soon after Nixon in China, the opera The Death of Klinghoffer (1991) was based on the Palestinian Liberation Front's 1985 hijacking and murder of Leon Klinghoffer and incited considerable controversy over its content and choice of subject matter. His next notable works include a Chamber Symphony (1992), a Violin Concerto (1993), the opera-oratorio El Niño (2000), the orchestral piece My Father Knew Charles Ives (2003) and the six-string electric violin concerto The Dharma at Big Sur. Adams won a Pulitzer Prize for Music for On the Transmigration of Souls (2002), a piece for orchestra and chorus commemorating the victims of the September 11, 2001, attacks. Continuing with historical subjects, Adams wrote the opera Doctor Atomic (2005), based on J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattan Project, and the building of the first atomic bomb. Later operas include A Flowering Tree (2006) and Girls of the Golden West (2017).

In many ways, Adams's music is developed from the minimalist tradition of Steve Reich and Philip Glass; however, he tends to more readily engage in the immense orchestral textures and climaxes of late Romanticism in the vein of Wagner and Mahler. His style is to a considerable extent a reaction against the modernist serialism promoted by the Second Viennese and Darmstadt School. In addition to the Pulitzer, Adams has received the Erasmus Prize, a Grawemeyer Award, five Grammy Awards, the Harvard Arts Medal, France's Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, and six honorary doctorates.

Life and career[edit]

Youth and early career[edit]

John Coolidge Adams was born in Worcester, Massachusetts, on February 15, 1947.[5] As an adolescent, he lived in Woodstock, Vermont for five years before moving to East Concord, New Hampshire,[6] and his family spent summers on the shores of Lake Winnipesaukee, where his grandfather ran a dance hall. Adams' family did not own a television, and did not have a record player until he was ten. However, both his parents were musicians; his mother was a singer with big bands, and his father was a clarinetist.[7] He grew up with jazz, Americana, and Broadway musicals, once meeting Duke Ellington at his grandfather's dance hall.[8] Adams also played baseball as a boy.[9]

In the third grade, Adams took up the clarinet, initially taking lessons from his father, Carl Adams, and later with Boston Symphony Orchestra bass clarinetist Felix Viscuglia. He also played in various local orchestras, concert bands, and marching bands while a student.[10][11] Adams began composing at the age of ten and first heard his music performed as a teenager.[12] He graduated from Concord High School in 1965.[13]

Adams next enrolled in Harvard University, where he earned a bachelor of arts, magnum cum laude, in 1969 and a master of arts in 1971, studying composition under Leon Kirchner, Roger Sessions, Earl Kim, Harold Shapero, and David Del Tredici.[5][3] As an undergraduate, he conducted Harvard's student ensemble, the Bach Society Orchestra, for a year and a half; his ambitious programming drew criticism in the student newspaper, where one of his concerts was called "the major disappointment of last week's musical offerings".[14][15] Adams also became engrossed by the strict modernism of the twentieth century (such as that of Boulez) while at Harvard, and believed that music had to continue progressing, to the extent that he once wrote a letter to Leonard Bernstein criticizing the supposed stylistic reactionism of Chichester Psalms.[16] By night, however, Adams enjoyed listening to The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, and Bob Dylan,[8][17] and has relayed he once stood in line at eight in the morning to purchase a copy of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[11]

Adams was the first student at Harvard to be allowed to write a musical composition for his senior thesis.[18][19] For his thesis, he wrote The Electric Wake for "electric" (i.e. amplified) soprano accompanied by an ensemble of "electric" strings, keyboards, harp, and percussion.[20] However, a performance could not be put together at the time, and Adams has never heard the piece performed.[18]

After graduating, Adams received a copy of John Cage's book Silence: Lectures and Writings from his mother. Largely shaken of his loyalty to modernism, he was inspired to move to San Francisco,[16] where he taught at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music from 1972 until 1982,[19] teaching classes and directing the school's New Music Ensemble. In the early 1970s, Adams wrote several pieces of electronic music for a homemade modular synthesizer he called the "Studebaker".[21] He also wrote American Standard, composed of three movements, a march, a hymn, and a jazz ballad, which was recorded and released on Obscure Records in 1975.[22]

Critical reception[edit]

Overview[edit]

Adams won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2003 for his 9/11 memorial piece, On the Transmigration of Souls.[44] Response to his output as a whole has been more divided, and Adams's works have been described as both brilliant and boring in reviews that stretch across both ends of the rating spectrum. Shaker Loops has been described as "hauntingly ethereal", while 1999's Naïve and Sentimental Music has been called "an exploration of a marvelously extended spinning melody".[73] The New York Times called 1996's Hallelujah Junction "a two-piano work played with appealingly sharp edges", and 2001's American Berserk "a short, volatile solo piano work".[74]

The most critically divisive pieces in Adams's collection are his historical operas. At first release, Nixon in China received mostly negative press feedback. Donal Henahan, writing in The New York Times, called the Houston Grand Opera world premiere of the work "worth a few giggles but hardly a strong candidate for the standard repertory" and "visually striking but coy and insubstantial".[75] James Wierzbicki for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described Adams's score as the weak point in an otherwise well-staged performance, noting the music as "inappropriately placid", "cliché-ridden in the abstract" and "[trafficked] heavily in Adams's worn-out Minimalist clichés".[76] With time, however, the opera has come to be revered as a great and influential production. Robert Hugill for Music and Vision called the production "astonishing ... nearly twenty years after its premier",[77] while The Guardian's Fiona Maddocks praised the score's "diverse and subtle palette" and Adams' "rhythmic ingenuity".[78]

More recently, The New York Times writer Anthony Tommasini commended Adams for his work conducting the American Composers Orchestra. The concert, which took place in April 2007 at Carnegie Hall, was a celebratory performance of Adams's work on his sixtieth birthday. Tommasini called Adams a "skilled and dynamic conductor", and noted that the music "was gravely beautiful yet restless".[79]

Specific operas

Interviews