MERS

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) is a viral respiratory infection caused by Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (MERS-CoV).[1] Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe depending on age and risk level.[6][1] Typical symptoms include fever, cough, diarrhea, and shortness of breath.[1] The disease is typically more severe in those with other health problems.[1][6]

For other uses, see Mers (disambiguation).

Middle East respiratory syndrome

(MERS)

Camel flu

Fever, cough, shortness of breath[1]

2 to 14 days post exposure[2]

2012–2020[3]

MERS-coronavirus (MERS-CoV)[1]

Hand washing, avoiding contact with camels and camel products[5]

34.4% risk of death (all countries)

2578 cases (as of October 2021)[3]

888[3]

The first case was identified in June 2012 by Egyptian physician Ali Mohamed Zaki at the Dr. Soliman Fakeeh Hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and most cases have occurred in the Arabian Peninsula.[1][6] Over 2,600 cases have been reported as of January 2021, including 45 cases in the year 2020.[3] About 35% of those who are diagnosed with the disease die from it.[1] Larger outbreaks have occurred in South Korea in 2015 and in Saudi Arabia in 2018.[7][1]

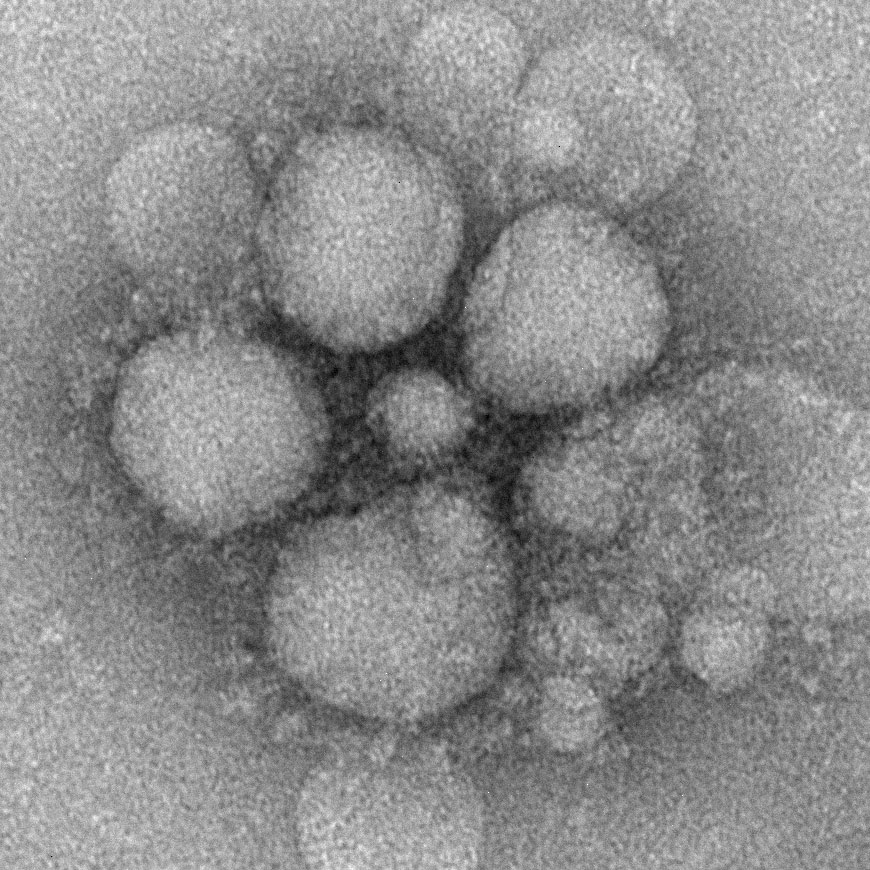

MERS-CoV is a virus in the coronavirus family believed to be originally from bats.[1] However, humans are typically infected from camels, either during direct contact or indirectly through respiratory droplets.[1] Spread between humans typically requires close contact with an infected person.[1] Its spread is uncommon outside of hospitals.[6] Thus, its risk to the global population is currently deemed to be significantly low.[6] Diagnosis is by rRT-PCR testing of blood and respiratory samples.[4]

As of 2021, there is no specific vaccine or treatment for the disease,[2] but a number are being developed.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that those who come in contact with camels wash their hands and not touch sick camels.[1] They also recommend that camel-based food products be appropriately cooked.[1] Treatments that help with the symptoms and support body functioning may be used.[1]

Previous infection with MERS can confer cross-reactive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and provide partial protection against COVID-19.[8] However, co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and MERS is possible and could lead to a recombination event.[9]

While the mechanism of spread of MERS-CoV is currently not known, based on experience with prior coronaviruses, such as SARS, the WHO currently recommends that all individuals coming into contact with MERS suspects should (in addition to standard precautions):

For procedures which carry a risk of aerosolization, such as intubation, the WHO recommends that care providers also:

The duration of infectivity is also unknown so it is unclear how long people must be isolated, but current recommendations are for 24 hours after resolution of symptoms. In the SARS outbreak the virus was not cultured from people after the resolution of their symptoms.[41]

It is believed that the existing SARS research may provide a useful template for developing vaccines and therapeutics against a MERS-CoV infection.[42][43] As of March 2020 there was one (DNA based) MERS vaccine which completed phase I clinical trials in humans,[44] and three others in progress all of which are viral vectored vaccines, two adenoviral vectored (ChAdOx1-MERS,[45][46] BVRS-GamVac[47]) and one MVA vectored (MVA-MERS-S[48]).[49]

Treatment[edit]

As of 2020, there is no specific vaccine or treatment for the disease.[2] Using extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) seems to improve outcomes significantly.[50]

Neither the combination of antivirals and interferons (ribavirin + interferon alfa-2a or interferon alfa-2b) nor corticosteroids improved outcomes.[51]

History[edit]

Collaborative efforts were used in the identification of the MERS-CoV.[102] Egyptian virologist Dr. Ali Mohamed Zaki isolated and identified a previously unknown coronavirus from the lungs of a 60-year-old Saudi Arabian man with pneumonia and acute kidney injury.[10] After routine diagnostics failed to identify the causative agent, Zaki contacted Ron Fouchier, a leading virologist at the Erasmus Medical Center (EMC) in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, for advice.[103] Fouchier sequenced the virus from a sample sent by Zaki.

Fouchier used a broad-spectrum "pan-coronavirus" real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) method to test for distinguishing features of a number of known coronaviruses (such as OC43, 229E, NL63, and SARS-CoV), as well as for RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), a gene conserved in all coronaviruses known to infect humans. While the screens for known coronaviruses were all negative, the RdRp screen was positive.[102]

On 15 September 2012, Dr. Zaki's findings were posted on ProMED-mail, the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases, a public health on-line forum.[15]

The United Kingdom's Health Protection Agency (HPA) confirmed the diagnosis of severe respiratory illness associated with a new type of coronavirus in a second patient, a 49-year-old Qatari man who had recently been flown into the UK. He died from an acute, serious respiratory illness in a London hospital.[102][20] In September 2012, the UK HPA named it the London1 novel CoV/2012 and produced the virus' preliminary phylogenetic tree, the genetic sequence of the virus[21] based on the virus's RNA obtained from the Qatari case.[11][104]

On 25 September 2012, the WHO announced that it was "engaged in further characterizing the novel coronavirus" and that it had "immediately alerted all its Member States about the virus and has been leading the coordination and providing guidance to health authorities and technical health agencies".[105] The Erasmus Medical Center (EMC) in Rotterdam "tested, sequenced and identified" a sample provided to EMC virologist Ron Fouchier by Ali Mohamed Zaki in November 2012.[18]

On 8 November 2012, in an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Zaki and co-authors from the Erasmus Medical Center published more details, including a tentative name, Human Coronavirus-Erasmus Medical Center (HCoV-EMC), the virus's genetic makeup, and closest relatives (including SARS).[10]

In May 2013, the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses adopted the official designation, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which was adopted by WHO to "provide uniformity and facilitate communication about the disease".[106] Prior to the designation, WHO had used the non-specific designation 'Novel coronavirus 2012' or simply 'the novel coronavirus'.[107]

Research[edit]

When rhesus macaques were given interferon-α2b and ribavirin and exposed to MERS, they developed less pneumonia than control animals.[108] Five critically ill people with MERS in Saudi Arabia with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and on ventilators were given interferon-α2b and ribavirin but all ended up dying of the disease. The treatment was started late in their disease (a mean of 19 days after hospital admission) and they had already failed trials of steroids so it remains to be seen whether it may have benefit earlier in the course of disease.[109][110] Another proposed therapy is inhibition of viral protease[111] or kinase enzymes.[112]

Researchers are investigating a number of medications, including using interferon, chloroquine, chlorpromazine, loperamide, lopinavir,[113] remdesivir and galidesivir as well as other agents such as mycophenolic acid,[114][115] camostat[116][117] and nitazoxanide.[118][119]