Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition

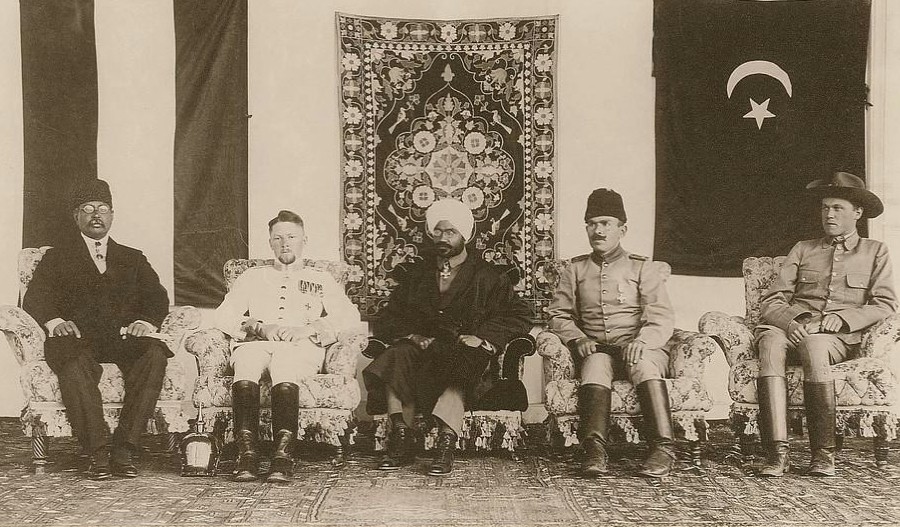

The Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition, also known as the Kabul Mission, was a diplomatic mission to Afghanistan sent by the Central Powers in 1915–1916. The purpose was to encourage Afghanistan to declare full independence from the British Empire, enter World War I on the side of the Central Powers, and attack British India. The expedition was part of the Hindu–German Conspiracy, a series of Indo-German efforts to provoke a nationalist revolution in India. Nominally headed by the exiled Indian prince Raja Mahendra Pratap, the expedition was a joint operation of Germany and Turkey and was led by the German Army officers Oskar Niedermayer and Werner Otto von Hentig. Other participants included members of an Indian nationalist organisation called the Berlin Committee, including Maulavi Barkatullah and Chempakaraman Pillai, while the Turks were represented by Kazim Bey, a close confidante of Enver Pasha.

Britain saw the expedition as a serious threat. Britain and its ally, the Russian Empire, unsuccessfully attempted to intercept it in Persia during the summer of 1915. Britain waged a covert intelligence and diplomatic offensive, including personal interventions by the Viceroy Lord Hardinge and King George V, to maintain Afghan neutrality.

The mission failed in its main task of rallying Afghanistan, under Emir Habibullah Khan, to the German and Turkish war effort, but it influenced other major events. In Afghanistan, the expedition triggered reforms and drove political turmoil that culminated in the assassination of the Emir in 1919, which in turn precipitated the Third Anglo-Afghan War. It influenced the Kalmyk Project of nascent Bolshevik Russia to propagate socialist revolution in Asia, with one goal being the overthrow of the British Raj. Other consequences included the formation of the Rowlatt Committee to investigate sedition in India as influenced by Germany and Bolshevism, and changes in the Raj's approach to the Indian independence movement immediately after World War I.

First Afghan expedition[edit]

In the first week of August 1914, the German Foreign Office and members of the military suggested attempting to use the pan-Islamic movement to destabilise the British Empire and begin an Indian revolution.[1] The argument was reinforced by Germanophile explorer Sven Hedin in Berlin two weeks later. General Staff memoranda in the last weeks of August confirmed the perceived feasibility of the plan, predicting that an invasion by Afghanistan could cause a revolution in India.[1]

With the outbreak of war, revolutionary unrest increased in India. Some Hindu and Muslim leaders secretly left to seek the help of the Central Powers in fomenting revolution.[2][10] The pan-Islamic movement in India, particularly the Darul Uloom Deoband, made plans for an insurrection in the North-West Frontier Province, with support from Afghanistan and the Central Powers.[11][12] Mahmud al Hasan, the principal of the Deobandi school, left India to seek the help of Galib Pasha, the Turkish governor of Hijaz, while another Deoband leader, Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi, travelled to Kabul to seek the support of the Emir of Afghanistan. They initially planned to raise an Islamic army headquartered at Medina, with an Indian contingent at Kabul. Mahmud al Hasan was to command this army.[12] While at Kabul, Maulana came to the conclusion that focusing on the Indian Freedom Movement would best serve the pan-Islamic cause.[13] Ubaidullah proposed to the Afghan Emir that he declare war against Britain.[14][15] Maulana Abul Kalam Azad was also involved in the movement prior to his arrest in 1916.[11]

Enver Pasha conceived an expedition to Afghanistan in 1914. He envisioned it as a pan-Islamic venture directed by Turkey, with some German participation. The German delegation to this expedition, chosen by Oppenheim and Zimmermann, included Oskar Niedermayer and Wilhelm Wassmuss.[9] An escort of nearly a thousand Turkish troops and German advisers was to accompany the delegation through Persia into Afghanistan, where they hoped to rally local tribes to jihad.[16]

In an ineffective ruse, the Germans attempted to reach Turkey by travelling overland through Austria-Hungary in the guise of a travelling circus, eventually reaching neutral Romania. Their equipment, arms, and mobile radios were confiscated when Romanian officials discovered the wireless aerials sticking out through the packaging of the "tent poles".[16] Replacements could not be arranged for weeks; the delegation waited at Constantinople. To reinforce the Islamic identity of the expedition, it was suggested that the Germans wear Turkish army uniforms, but they refused. Differences between Turkish and German officers, including the reluctance of the Germans to accept Turkish control, further compromised the effort.[17] Eventually, the expedition was aborted.

The attempted expedition had a significant consequence. Wassmuss left Constantinople to organise the tribes in south Persia to act against British interests. While evading British capture in Persia, Wassmuss inadvertently abandoned his codebook. Its recovery by Britain allowed the Allies to decipher German communications, including the Zimmermann Telegram in 1917. Niedermayer led the group following Wassmuss's departure.[17]

Mission's conclusion[edit]

In the end, Emir Habibullah returned to his vacillating inactivity. He was aware the mission had found support within his council and had excited his volatile subjects. Four days after the draft treaty was signed, Habibullah called for a durbar, a grand meeting where a jihad was expected to be called. Instead, Habibullah reaffirmed his neutrality, explaining that the war's outcome was still unpredictable and that he stood for national unity.[58] Throughout the spring of 1916, he continuously deflected the mission's overtures and gradually increased the stakes, demanding that India rise in revolution before he began his campaign. It was clear to Habibullah that for the treaty to hold any value, it required the Kaiser's signature, and that for Germany to even attempt to honour the treaty, she would have to be in a strong position in the war. It was a good insurance policy for Habibullah.[58]

Meanwhile, he had received worrying British intelligence reports that said he was in danger of being assassinated and his country may face a coup d'état. His tribesmen were unhappy at Habibullah's perceived subservience to the British, and his council and relatives openly spoke of their suspicions at his inactivity. Habibullah began purging his court of officials who were known to be close to Nasrullah and Amanullah. He recalled emissaries he had sent to Persia for talks with Germany and Turkey for military aid.[58] Meanwhile, the war took a turn for the worse for the Central Powers. The Arab revolt against Turkey and the loss of Erzurum to the Russians ended the hopes of sending a Turkish division to Afghanistan.[58] The German influence in Persia also declined rapidly, ending the hopes that Goltz Pasha could lead a Persian volunteer division into Afghanistan.[59] The mission came to realise that the Emir deeply mistrusted them. A further attempt by British intelligence to feed false information to the mission, purportedly originating from Goltz Pasha, convinced von Hentig of the Emir's lack of trust.[59] A last offer was made by Nasrullah in May 1916 to remove Habibullah from power and lead the frontier tribes in a campaign against British India.[59] However, von Hentig knew it would come to nothing, and the Germans left Kabul on 21 May 1916. Niedermayer instructed Wagner to stay in Herat as a liaison officer. The Indian members also stayed, persisting in their attempts at an alliance.[59][60][61]

Though ancient rules of hospitality had protected the expedition, they knew that once they were out of the Emir's lands, the Anglo-Russian forces as well as the marauding tribesmen of Persia would chase them mercilessly. The party split up into several groups, each independently making its way back to Germany.[60] Niedermayer headed west, attempting to run the Anglo-Russian Cordon and escape through Persia, while von Hentig made for the route over the Pamir Mountains towards Chinese Central Asia. Having served in Peking before the war, von Hentig was familiar with the region and planned to make Yarkand a base from which to make a last attempt to create local Muslim unrest against Anglo-Russian interests in the region.[60] He later escaped over the Hindu Kush, avoiding his pursuers for 130 days as he made his way on foot and horseback through Chinese Turkestan, over the Gobi Desert, and through China and Shanghai. From there, he stowed away on an American vessel to Honolulu. Following the American declaration of war, he was exchanged as a diplomat. Travelling via San Francisco, Halifax, and Bergen, he finally reached Berlin on 9 June 1917.[62] Meanwhile, Niedermayer escaped towards Persia through Russian Turkestan. Robbed and left for dead, a wounded Niedermayer was at times reduced to begging before he finally reached friendly lines, arriving in Tehran on 20 July 1916.[62][63] Wagner left Herat on 25 October 1917, making his way through northern Persia to reach Turkey on 30 January 1918. At Chorasan, he tried to rally Persian democratic and nationalist leaders, who promised to raise an army of 12,000 if Germany provided military assistance.[61]

Mahendra Pratap attempted to seek an alliance with Tsar Nicholas II from February 1916, but his messages remained unacknowledged.[56] The 1917 Kerensky government refused a visa to Pratap, aware that he was considered a "dangerous seditionist" by the British government.[56] Pratap was able to correspond more closely with Lenin's Bolshevik government. At the invitation of Turkestan authorities, he visited Tashkent in February 1918. This was followed by a visit to Petrograd, where he met Trotsky. He and Barkatullah remained in touch with the German government and with the Berlin Committee through the latter's secret office in Stockholm. After Lenin's coup, Pratap at times acted as liaison between the Afghan government and the Germans, hoping to revive the Indian cause. In 1918, Pratap suggested to Trotsky a joint German-Russian invasion of the Indian frontiers. He recommended a similar plan to Lenin in 1919. He was accompanied in Moscow by Indian revolutionaries of the Berlin Committee, who were at the time turning to communism.[56][61]

Influence[edit]

On Afghanistan[edit]

The expedition greatly disturbed Russian and British influence in Central and South Asia, raising concerns about the security of their interests in the region. Further, it nearly succeeded in propelling Afghanistan into the war.[57] The offers and liaisons made between the mission and figures in Afghani politics influenced the political and social situation in the country, starting a process of political change.[57]

Epilogue[edit]

After 1919, members of the Provisional Government of India, as well as Indian revolutionaries of the Berlin Committee, sought Lenin's help for the Indian independence movement.[57] Some of these revolutionaries were involved in the early Indian communist movement. With a price on his head, Mahendra Pratap travelled under an Afghan nationality for a number of years before returning to India after 1947. He was subsequently elected to the Indian parliament.[94] Barkatullah and C.R. Pillai returned to Germany after a brief period in Russia. Barkatullah later moved back to the United States, where he died in San Francisco in 1927. Pillai was associated with the League against Imperialism in Germany, where he witnessed the Nazi rise to power. Pillai was killed in 1934. At the invitation of the Soviet leadership, Ubaidullah proceeded to Soviet Russia, where he spent seven months as a guest of the state. During his stay, he studied the ideology of socialism and was impressed by Communist ideals.[95] He left for Turkey, where he initiated the third phase of the Waliullah Movement in 1924. He issued the charter for the independence of India from Istanbul. Ubaidullah travelled through the holy lands of Islam before permission for his return was requested by the Indian National Congress. After he was allowed back in 1936, he undertook considerable work in the interpretation of Islamic teachings. Ubaidullah died on 22 August 1944 at Deen Pur, near Lahore.[96][97]

Both Niedermayer and von Hentig returned to Germany, where they enjoyed celebrated careers.[94] On von Hentig's recommendation, Niedermayer was knighted and bestowed with the Military Order of Max Joseph. He was asked to lead a third expedition to Afghanistan in 1917, but declined. Niedermayer served in the Reichswehr before retiring in 1933 and joining the University of Berlin. He was recalled to active duty during World War II, serving in Ukraine. He was taken prisoner at the end of the war and died in a Soviet prisoner of war camp in 1948.

Werner von Hentig was honoured with the House Order of Hohenzollern by the Kaiser himself. He was considered for the Pour le Mérite by the German Foreign Office, but his superior officer, Bothmann-Hollweg, was not eligible to recommend him since the latter did not hold the honour himself. Von Hentig embarked on a diplomatic career, serving as consul general to a number of countries. He influenced the decision to limit the German war effort in the Middle East during World War II.[94] In 1969, von Hentig was invited by Afghan King Mohammed Zahir Shah to be guest of honour at celebrations of the fiftieth anniversary of Afghan independence. Von Hentig later penned (in German) his memoirs of the expedition.[94]