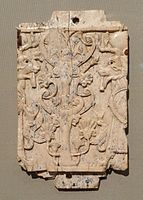

Nimrud ivories

The Nimrud ivories are a large group of small carved ivory plaques and figures dating from the 9th to the 7th centuries BC that were excavated from the Assyrian city of Nimrud (in modern Ninawa in Iraq) during the 19th and 20th centuries. The ivories mostly originated outside Mesopotamia and are thought to have been made in the Levant and Egypt, and have frequently been attributed to the Phoenicians due to a number of the ivories containing Phoenician inscriptions.[2] They are foundational artefacts in the study of Phoenician art, together with the Phoenician metal bowls, which were discovered at the same time but identified as Phoenician a few years earlier. However, both the bowls and the ivories pose a significant challenge as no examples of either – or any other artefacts with equivalent features – have been found in Phoenicia or other major colonies (e.g. Carthage, Malta, Sicily).[3]

Nimrud ivories

9th to 7th centuries BC

Neo-Assyrian

British Museum, London, National Museum of Iraq, Baghdad, and elsewhere

Most are fragments of the original forms; there are over 1,000 significant pieces, and many more very small fragments. They are carved with motifs typical of those regions and were used to decorate a variety of high-status objects, including pieces of furniture, chariots and horse-trappings, weapons, and small portable objects of various kinds. Many of the ivories would have originally been decorated with gold leaf or semi-precious stones, which were stripped from them at some point before their final burial. A large group were found in what was apparently a palace storeroom for unused furniture. Many were found at the bottom of wells, having apparently been dumped there when the city was sacked during the poorly-recorded collapse of the Assyrian Empire between 616 BC and 599 BC.[4]

Many of the ivories were taken to the United Kingdom and were deposited in (though not owned by) the British Museum. In 2011, the Museum acquired most of the British-held ivories through a donation and purchase and is to put a selection on view.[5] It is intended that the remainder will be returned to Iraq. A significant number of ivories were already held by Iraqi institutions but many have been lost or damaged through war and looting. Other museums around the world have groups of pieces.

A number of the ivories contain Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions – a few contain a number of words, and many more contain single letters. Some of these were found in the mid-nineteenth century by Layard and Loftus (in particular a knob inscribed "property of Milki-ram " [lmlkrm]), and more were found in 1961 by Mallowan and Oates. Of the latter, the most significant finds were excavated in "Fort Shalmaneser" in the southeast of the Nimrud site.[17] Alan Millard published a series of these in 1962; the code "ND" is the standard excavation code for "Nimrud Documents":[17]

They have been compared to the Arslan Tash ivory inscription and the Ur Box inscription.[17]

One of the fragmentary ivories found at Nimrud carries the name of Hazael. This was probably king Hazael mentioned in the Bible.[18]

Ivories from Nimrud are held at a number of institutions across the world:

Catalogues[edit]

The Nimrud Ivories are being published in a series of scholarly catalogues. Many of these are available free online from the British Institute for the Study of Iraq (BISI): links here.