Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD),[a] is a type of chronic liver disease. This condition is diagnosed when there is excessive fat build-up in the liver (hepatic steatosis), and at least one metabolic risk factor.[1][3][4] When there is also increased alcohol intake, the term MetALD, or metabolic dysfunction and alcohol associated/related liver disease is used, and differentiated from alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) where alcohol is the predominant cause of the steatotic liver disease.[1][12] The terms non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH, now MASH) have been used to describe different severities, the latter indicating the presence of further liver inflammation.[4][5][8] NAFL is less dangerous than NASH and usually does not progress to it,[4] but this progression may eventually lead to complications, such as cirrhosis, liver cancer, liver failure, and cardiovascular disease.[4][13]

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease

Asymptomatic in the early stages

In later stages:

* Deposits of cholesterol on the eye lids

* Fatigue

* Crusty red nodules

* Digestive issues

Lastly causes liver disease and eventually liver failure

Long term

Genetic, environmental

Obesity, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, liver disease

Ultrasound,

Coexisting metabolic disorders,

Liver biopsy

Depends on type[8]

24% in worldwide population, 80% in obese, 20% in normal-weight

Obesity and type 2 diabetes are strong risk factors for MASLD.[7] Other risks include being overweight, metabolic syndrome (defined as at least three of the five following medical conditions: abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high serum triglycerides, and low serum HDL cholesterol), a diet high in fructose, and older age.[4][8] Obtaining a sample of the liver after excluding other potential causes of fatty liver can confirm the diagnosis.[3][7][8]

Treatment for MASLD is weight loss by dietary changes and exercise;[5][14][15] bariatric surgery can improve or resolve severe cases.[14][16] There is some evidence for SGLT-2 inhibitors, GLP-1 agonists, pioglitazone, and vitamin E in the treatment of MASLD.[17][18] In March 2024, resmetirom was the first drug approved by the FDA for MASH.[19] Those with MASH have a 2.6% increased risk of dying per year.[5]

MASLD is the most common liver disorder in the world; about 25% of people have it.[20] It is very common in developed nations, such as the United States, and affected about 75 to 100 million Americans in 2017.[21][22][23][24] Over 90% of obese, 60% of diabetic, and up to 20% of normal-weight people develop MASLD.[25][26] MASLD was the leading cause of chronic liver disease[24][25] and the second most common reason for liver transplantation in the United States and Europe in 2017.[14] MASLD affects about 20 to 25% of people in Europe.[16] In the United States, estimates suggest that 30% to 40% of adults have MASLD, and about 3% to 12% of adults have MASH.[4] The annual economic burden was about US$103 billion in the United States in 2016.[25]

Definition[edit]

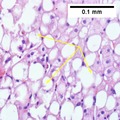

An abnormal accumulation of fat in the liver in the absence of secondary causes of fatty liver, such as significant alcohol use, viral hepatitis, or medications that can induce fatty liver, was the definition of NAFLD.[20] However, the term MASLD accepts there may be other conditions present, but focuses on the metabolic abnormalities contributing to the disorder.[1][12] MASLD encompasses a continuum of liver abnormalities, from metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver (MASL, simple steatosis) to Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH). These diseases begin with fatty accumulation in the liver (hepatic steatosis). A liver can remain fatty without disturbing liver function (MASL), but by various mechanisms and possible insults to the liver, it may also progress into steatohepatitis (MASH), a state in which steatosis is combined with inflammation and sometimes fibrosis.[1] MASH can then lead to complications such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.[3][5][27]

The new name, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), was proposed after 70% of a panel of experts expressed support for this name.[1] This new name was adopted in 2023.[1][10]

Risk factors[edit]

Genetics[edit]

Two-thirds of families with a history of diabetes type 2 report more than one family member having MASLD. There is a higher risk of fibrosis for family members where someone was diagnosed with MASH.[27] Asian populations are more susceptible to metabolic syndrome and MASLD than their western counterparts.[7] Hispanic persons have a higher prevalence of MASLD than white individuals, whereas the lowest prevalence is observed in black individuals.[25] MASLD is twice as prevalent in men as in women,[5] which might be explained by lower levels of estrogen in men.[32]

Genetic variations in two genes are associated with MASLD: non-synonymous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in PNPLA3 and TM6SF2. Both correlate with MASLD presence and severity, but their roles for diagnosis remain unclear.[25][33] Although NAFLD has a genetic component, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) does not recommend screening family members as there is not enough confirmation of heritability,[5] although there is some evidence from familial aggregation and twin studies.[25]

From diet[edit]

According to the Asia-Pacific Working Group (APWG) on MASLD, overnutrition is a major factor of MASLD and MASH, particularly for lean MASLD.[7] Diet composition and quantity, in particular omega-6 fatty acid and fructose, have important roles in disease progression from MASL to MASH and fibrosis.[34][35] Choline deficiency can lead to the development of MASLD.[36]

Higher consumption of processed, red, and organ meats have been associated with higher risk of developing MASLD.[37][38][39] Some research also suggests eggs are also associated with developing MASLD.[40][41] On the other hand, studies have found healthful plant foods such as legumes and nuts, to be associated with a lower risk of developing MASLD.[42][43] Two different studies have found healthy plant-based diets rich in healthy plant foods and low in animal foods to be associated with a lower risk of developing MASLD, even after adjusting for BMI.[44][45]

From lifestyle[edit]

Habitual snoring may be a risk factor for MASLD. Severe snoring often signals the presence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSAS), a much more serious breathing condition. Blockage or narrowing of the airways, even temporarily, can cause the body to experience lowered oxygen levels in the blood. This in turn may cause a variety of changes within the body such as tissue inflammation, increased insulin resistance, and liver injury.[46] A prospective cohort study found the association between habitual snoring and MASLD development to be significant, and the trend was noted to be most prominent in lean individuals.[47]

Prognosis[edit]

The average progression rate from one stage of liver fibrosis to the next in humans with NASH is estimated to be seven years. The course of progression varies with different clinical manifestations among individuals.[25][27][120] Fibrosis in humans with MASH progressed more rapidly than in humans with MASLD.[13] Obesity predicts a worse long-term outcome than for lean individuals.[121][122] In the Asia-Pacific region, about 25% of MASLD cases progress to MASH under three years, but only a low proportion (3.7%) develop advanced liver fibrosis.[7] An international study showed that people with MASLD with advanced fibrosis had a 10-year survival rate of 81.5%.[5]

MASLD is a risk factor for fibrosis, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and death from cardiovascular causes based on very-low to low-quality evidence from observational studies.[65][123] Although MASLD can cause cirrhosis and liver failure and liver cancer, most deaths among people with NAFLD are attributable to cardiovascular disease.[51] According to a meta-analysis of 34,000 people with MASLD over seven years, these individuals have a 65% increased risk of developing fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular events when compared to those without MASLD.[27]

MASLD and NASH increase the risk of liver cancer. Cirrhosis and liver cancer induced by NAFLD were the second cause of liver transplantation in the US in 2017. Liver cancer develops in NASH in the absence of cirrhosis in 45% in the cases,[124] and people with NASH cirrhosis have an increased risk of liver cancer. The rate of liver cancer associated with NASH increased fourfold between 2002 and 2012 in the US, which is more than any other cause of liver cancer. MASLD constitutes the third most common risk factor for liver cancer.[125] NAFLD and NASH were found to worsen with cirrhosis in respectively 2–3% and 15–20% of the people over a 10–20 year period.[13] Cirrhosis is found in only about 50% of people with MASLD and with liver cancer, so that liver cancer and cirrhosis are not always linked.[14]

MASLD is a precursor of metabolic syndrome, although a bidirectional influence is possible.[126][127][128] The presence and stage of fibrosis are the strongest prognostic factors for liver-related events and mortality, in particular for MASLD.[25]

History[edit]

The first acknowledged case of obesity-related non-alcoholic fatty liver was observed in 1952 by Samuel Zelman.[136][137] Zelman started investigating after observing a fatty liver in a hospital employee who drank more than twenty bottles of Coca-Cola a day. He then went on to design a trial for a year and a half on 20 obese people who were not alcoholic, finding that about half of them had substantially fatty livers.[136] Fatty liver was, however, linked to diabetes since at least 1784[138] — an observation picked up again in the 1930s.[139] Studies in experimental animals implicated choline inadequacy in the 1920s and excess sugar consumption in 1949.[140]

The name "non-alcoholic steatohepatitis" (NASH) was later defined in 1980 by Jurgen Ludwig and his colleagues from the Mayo Clinic[141] to raise awareness of the existence of this pathology, as similar reports previously were dismissed as "patients' lies".[137] This paper was mostly ignored at the time but eventually came to be seen as a landmark paper, and starting in the mid-1990s, the condition began to be intensively studied, with a series of international meetings being held on the topic since 1998.[142] The broader NAFLD term started to be used around 2002.[142][143] Diagnostic criteria began to be worked out, and in 2005 the Pathology Committee of the NIH NASH Clinical Research Network proposed the NAS scoring system.[142]

Society and culture[edit]

Political recommendations[edit]

EASL recommends Europe's public health authorities to "restrict advertising and marketing of sugar-sweetened beverages and industrially processed foods high in saturated fat, sugar, and salt", as well as "fiscal measures to discourage the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and legislation to ensure that the food industry improves labeling and the composition of processed foods", as well as "public awareness campaigns on liver disease, highlighting that it is not only linked to excessive consumption of alcohol".[134]

Media[edit]

In France, the French syndicate of non-alcoholic beverages "Boissons Rafraîchissantes de France" (that included soft drink producers such as Coca-Cola France, Orangina, PepsiCo France) was denounced by the French journal fr:Canard Enchainé for misleading consumers using a communication on their website titled "Better understanding the NASH pathology",[144] explaining that "NASH pathology is sometimes called the soda illness by language abuse or an unfortunate semantic shortcut, as it is not directly linked to the consumption of non-alcoholic beverages". This page and others on the same website, such as one titled "Say no to disinformation," were since then removed.[145]

Children[edit]

Pediatric MASLD was first reported in 1983.[146][147] It is the most common chronic liver disease among children and adolescents since at least 2007, affecting 10 to 20% of them in the US in 2016.[25][147][148] MASLD is associated with metabolic syndrome, which is a cluster of risk factors that contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Studies have demonstrated that abdominal obesity and insulin resistance, in particular, are significant contributors to the development of NAFLD.[149][150][151][152][153] Coexisting liver diseases, such as hepatitis C and cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, are also associated with an increased risk of NAFLD.[28][51] Some children were diagnosed as early as two years old, with a mean age of diagnosis between 11 and 13 years old.[147] The mean age is usually above 10 years, as children can also report non-specific symptoms and are thus difficult to diagnose for MASLD.[147]

Boys are more likely to be diagnosed with MASLD than girls.[28][133] Overweight, or even weight gain, in childhood and adolescence, is associated with an increased risk of MASLD later in life, with adult MASLD predicted in a 31-year follow-up study by risk factors during childhood including BMI, plasma insulin levels, male sex, genetic background (PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 variants) and low birth weight, an emerging risk factor for adulthood MASLD.[25][28] In a study, simple steatosis was present in up to 45% in children with a clinical suspicion of MASLD.[28] Children with simple steatosis have a worse prognosis than adults, with significantly more of them progressing from NAFLD to NASH compared to adults. Indeed, 17-25% of children with MASLD develop MASH in general, and up to 83% for children with severe obesity (versus 29% for adults), further suggesting that hepatic fibrosis seems to follow a more aggressive clinical course in children compared to adults.[147]

Early diagnosis of MASLD in children may help prevent the development of liver disease during adulthood.[151][154] This is challenging as most children with MASLD are asymptomatic, with only 42-59% showing abdominal pain.[28][154] Other symptoms might be present, such as right upper quadrant pain or acanthosis nigricans, the latter of which is often present in children with NASH. An enlarged liver occurs in 30–40% of children with NAFLD.[28]

The AASLD recommends a diagnostic liver biopsy in children when the diagnosis is unclear or before starting a potentially hepatotoxic medical therapy.[5] The EASL suggests using fibrosis tests such as elastography, acoustic radiation force impulse imaging, and serum biomarkers to reduce the number of biopsies.[16] In follow up, NICE guidelines recommend that healthcare providers offer children regular MASLD screening for advanced liver fibrosis every two years using the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) blood test.[65] Several studies also suggest magnetic resonance elastography as an alternative to the less reliable ultrasonography.[28]

Intensive lifestyle modifications, including physical activity and dietary changes, are the first line of treatment according to AASLD and EASL as it improves the liver histology and aminotransferase levels. In terms of pharmacological treatment, the AASLD and EASL do not recommend metformin, but vitamin E may improve liver health for some children.[5][16] The NICE advises the use of vitamin E for children with advanced liver fibrosis, whether they have diabetes or not.[65] The only treatment shown to be effective in childhood MASLD is weight loss.[155]

Some evidence indicates that maternal undernutrition or overnutrition increases a child's susceptibility to NASH and hastens its progression.[156]

Research[edit]

Diagnosis and biomarkers[edit]

Since a MASLD diagnosis based on a liver biopsy is invasive and makes it difficult to estimate epidemiology, it is a high research priority to find accurate, inexpensive, and noninvasive methods of diagnosing and monitoring MASLD disease and its progression.[33][157] The search for these biomarkers of MASLD, NAFL, and NASH involves lipidomics, medical imaging, proteomics, blood tests, and scoring systems.[33]

According to a review, proton density fat fraction estimation by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI-PDFF) may be considered the most accurate and even gold standard test to quantify hepatic steatosis. They recommend ultrasound-based transient elastography to accurately diagnose both fibrosis and cirrhosis in a routine clinical setting, with more objectivity than ultrasonography but with lower accuracy than magnetic resonance elastography; and plasma cytokeratin 18 (CK18) fragment levels to be a moderately accurate biomarker of steatohepatitis.[33] However, transient elastography can fail for people with pre-hepatic portal hypertension.[69]