Nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare, also known as atomic warfare, is a military conflict or prepared political strategy that deploys nuclear weaponry. Nuclear weapons are weapons of mass destruction; in contrast to conventional warfare, nuclear warfare can produce destruction in a much shorter time and can have a long-lasting radiological result. A major nuclear exchange would likely have long-term effects, primarily from the fallout released, and could also lead to secondary effects, such as "nuclear winter",[1][2][3][4][5][6] nuclear famine, and societal collapse.[7][8][9] A global thermonuclear war with Cold War-era stockpiles, or even with the current smaller stockpiles, may lead to various scenarios including the extinction of the human species.[10]

Not to be confused with NukeWar or nukewar (warez). "Nuclear War" and "Nuclear strike" redirect here. For other uses, see Nuclear War (disambiguation). "Atomic war" redirects here. Not to be confused with Atomic Wars.

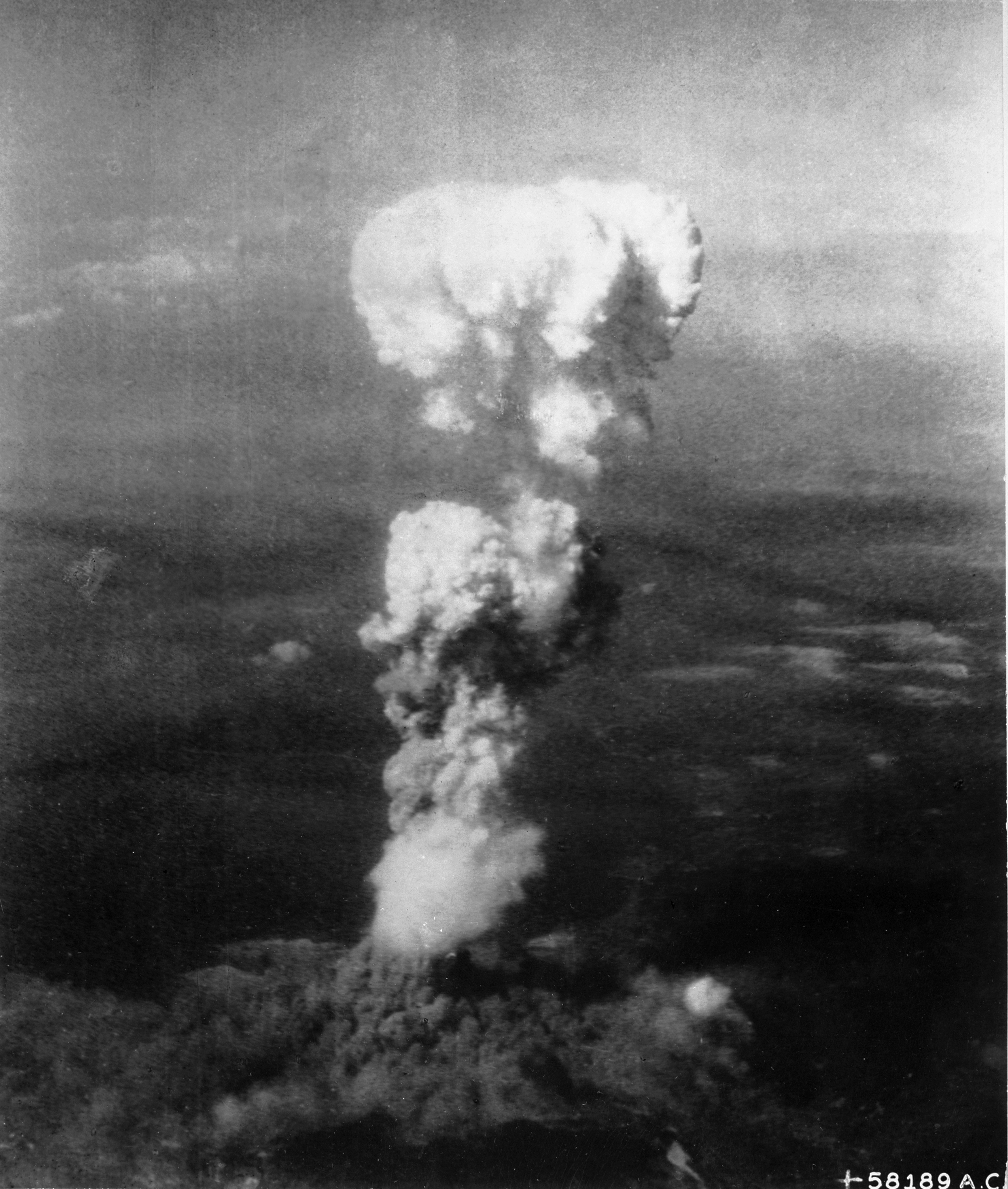

To date, the only use of nuclear weapons in armed conflict occurred in 1945 with the American atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On August 6, 1945, a uranium gun-type device (code name "Little Boy") was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later, on August 9, a plutonium implosion-type device (code name "Fat Man") was detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki. Together, these two bombings resulted in the deaths of approximately 200,000 people and contributed to the surrender of Japan, which occurred before any further nuclear weapons could be deployed.

After World War II, nuclear weapons were also developed by the Soviet Union (1949), the United Kingdom (1952), France (1960), and the People's Republic of China (1964), which contributed to the state of conflict and extreme tension that became known as the Cold War. In 1974, India, and in 1998, Pakistan, two countries that were openly hostile toward each other, developed nuclear weapons. Israel (1960s) and North Korea (2006) are also thought to have developed stocks of nuclear weapons, though it is not known how many. The Israeli government has never admitted nor denied having nuclear weapons, although it is known to have constructed the reactor and reprocessing plant necessary for building nuclear weapons.[11] South Africa also manufactured several complete nuclear weapons in the 1980s, but subsequently became the first country to voluntarily destroy their domestically made weapons stocks and abandon further production (1990s).[12][13] Nuclear weapons have been detonated on over 2,000 occasions for testing purposes and demonstrations.[14][15]

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the resultant end of the Cold War, the threat of a major nuclear war between the two nuclear superpowers was generally thought to have declined.[16] Since then, concern over nuclear weapons has shifted to the prevention of localized nuclear conflicts resulting from nuclear proliferation, and the threat of nuclear terrorism. However, the threat of nuclear war is considered to have resurged after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, particularly with regard to Russian threats to use nuclear weapons during the invasion.[17][18]

Since 1947, the Doomsday Clock of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has visualized how close the world is to a nuclear war. The Doomsday Clock reached high points in 1953, when the Clock was set to two minutes until midnight after the U.S. and the Soviet Union began testing hydrogen bombs, and in 2018, following the failure of world leaders to address tensions relating to nuclear weapons and climate change issues.[19] Since 2023, the Clock has been set at 90 seconds to midnight, the closest it has ever been.[20] The most recent advance of the Clock's time setting was largely attributed to the risk of nuclear escalation that arose from the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[21]

Types of nuclear warfare[edit]

Nuclear warfare scenarios are usually divided into two groups, each with different effects and potentially fought with different types of nuclear armaments.

The first, a limited nuclear war[22] (sometimes attack or exchange), refers to the controlled use of nuclear weapons, whereby the implicit threat exists that a nation can still escalate their use of nuclear weapons. For example, using a small number of nuclear weapons against strictly military targets could be escalated through increasing the number of weapons used, or escalated through the selection of different targets. Limited attacks are thought to be a more credible response against attacks that do not justify all-out retaliation, such as an enemy's limited use of nuclear weapons.[23]

The second, a full-scale nuclear war, could consist of large numbers of nuclear weapons used in an attack aimed at an entire country, including military, economic, and civilian targets. Such an attack would almost certainly destroy the entire economic, social, and military infrastructure of the target nation, and would likely have a devastating effect on Earth's biosphere.[7][24]

Some Cold War strategists such as Henry Kissinger[25] argued that a limited nuclear war could be possible between two heavily armed superpowers (such as the United States and the Soviet Union). Some predict, however, that a limited war could potentially "escalate" into a full-scale nuclear war. Others have called limited nuclear war "global nuclear holocaust in slow motion", arguing that—once such a war took place—others would be sure to follow over a period of decades, effectively rendering the planet uninhabitable in the same way that a "full-scale nuclear war" between superpowers would, only taking a much longer (and arguably more agonizing) path to the same result.

Even the most optimistic predictions of the effects of a major nuclear exchange foresee the death of many millions of victims within a very short period of time. Such predictions usually include the breakdown of institutions, government, professional and commercial, vital to the continuation of civilization. The resulting loss of vital affordances (food, water and electricity production and distribution, medical and information services, etc.) would account for millions more deaths. More pessimistic predictions argue that a full-scale nuclear war could potentially bring about the extinction of the human race, or at least its near extinction, with only a relatively small number of survivors (mainly in remote areas) and a reduced quality of life and life expectancy for centuries afterward. However, such predictions, assuming total war with nuclear arsenals at Cold War highs, have not been without criticism.[4] Such a horrific catastrophe as global nuclear warfare would almost certainly cause permanent damage to most complex life on the planet, its ecosystems, and the global climate.[5]

A study presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in December 2006 asserted that a small-scale regional nuclear war could produce as many direct fatalities as all of World War II and disrupt the global climate for a decade or more. In a regional nuclear conflict scenario in which two opposing nations in the subtropics each used 50 Hiroshima-sized nuclear weapons (c. 15 kiloton each) on major population centers, the researchers predicted fatalities ranging from 2.6 million to 16.7 million per country. The authors of the study estimated that as much as five million tons of soot could be released, producing a cooling of several degrees over large areas of North America and Eurasia (including most of the grain-growing regions). The cooling would last for years and could be "catastrophic", according to the researchers.[26]

Either a limited or full-scale nuclear exchange could occur during an accidental nuclear war, in which the use of nuclear weapons is triggered unintentionally. Postulated triggers for this scenario have included malfunctioning early warning devices and/or targeting computers, deliberate malfeasance by rogue military commanders, consequences of an accidental straying of warplanes into enemy airspace, reactions to unannounced missile tests during tense diplomatic periods, reactions to military exercises, mistranslated or miscommunicated messages, and others.

A number of these scenarios actually occurred during the Cold War, though none resulted in the use of nuclear weapons.[27] Many such scenarios have been depicted in popular culture, such as in the 1959 film On the Beach, the 1962 novel Fail-Safe, the 1964 film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, the 1983 film WarGames, and the 1984 film Threads.