Occam's razor

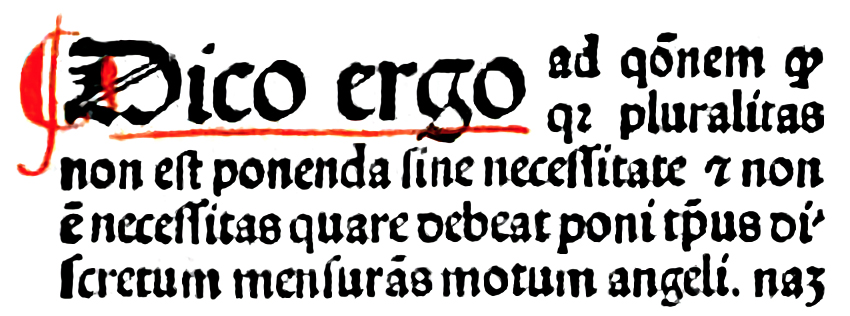

In philosophy, Occam's razor (also spelled Ockham's razor or Ocham's razor; Latin: novacula Occami) is the problem-solving principle that recommends searching for explanations constructed with the smallest possible set of elements. It is also known as the principle of parsimony or the law of parsimony (Latin: lex parsimoniae). Attributed to William of Ockham, a 14th-century English philosopher and theologian, it is frequently cited as Entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem, which translates as "Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity",[1][2] although Occam never used these exact words. Popularly, the principle is sometimes paraphrased as "The simplest explanation is usually the best one."[3]

"Ockham's razor" redirects here. For the aerial theatre company, see Ockham's Razor Theatre Company. For the Australian radio program, see Radio National.This philosophical razor advocates that when presented with competing hypotheses about the same prediction and both theories have equal explanatory power one should prefer the hypothesis that requires the fewest assumptions[4] and that this is not meant to be a way of choosing between hypotheses that make different predictions. Similarly, in science, Occam's razor is used as an abductive heuristic in the development of theoretical models rather than as a rigorous arbiter between candidate models.[5][6]

Justifications[edit]

Aesthetic[edit]

Prior to the 20th century, it was a commonly held belief that nature itself was simple and that simpler hypotheses about nature were thus more likely to be true. This notion was deeply rooted in the aesthetic value that simplicity holds for human thought and the justifications presented for it often drew from theology. Thomas Aquinas made this argument in the 13th century, writing, "If a thing can be done adequately by means of one, it is superfluous to do it by means of several; for we observe that nature does not employ two instruments [if] one suffices."[31]

Beginning in the 20th century, epistemological justifications based on induction, logic, pragmatism, and especially probability theory have become more popular among philosophers.[7]

Empirical[edit]

Occam's razor has gained strong empirical support in helping to converge on better theories (see Uses section below for some examples).

In the related concept of overfitting, excessively complex models are affected by statistical noise (a problem also known as the bias–variance tradeoff), whereas simpler models may capture the underlying structure better and may thus have better predictive performance. It is, however, often difficult to deduce which part of the data is noise (cf. model selection, test set, minimum description length, Bayesian inference, etc.).

Controversial aspects[edit]

Occam's razor is not an embargo against the positing of any kind of entity, or a recommendation of the simplest theory come what may.[a] Occam's razor is used to adjudicate between theories that have already passed "theoretical scrutiny" tests and are equally well-supported by evidence.[b] Furthermore, it may be used to prioritize empirical testing between two equally plausible but unequally testable hypotheses; thereby minimizing costs and wastes while increasing chances of falsification of the simpler-to-test hypothesis.

Another contentious aspect of the razor is that a theory can become more complex in terms of its structure (or syntax), while its ontology (or semantics) becomes simpler, or vice versa.[c] Quine, in a discussion on definition, referred to these two perspectives as "economy of practical expression" and "economy in grammar and vocabulary", respectively.[86]

Galileo Galilei lampooned the misuse of Occam's razor in his Dialogue. The principle is represented in the dialogue by Simplicio. The telling point that Galileo presented ironically was that if one really wanted to start from a small number of entities, one could always consider the letters of the alphabet as the fundamental entities, since one could construct the whole of human knowledge out of them.

Instances of using Occam's razor to justify belief in less complex and more simple theories have been criticized as using the razor inappropriately. For instance Francis Crick stated that "While Occam's razor is a useful tool in the physical sciences, it can be a very dangerous implement in biology. It is thus very rash to use simplicity and elegance as a guide in biological research."[87]

Anti-razors[edit]

Occam's razor has met some opposition from people who consider it too extreme or rash. Walter Chatton (c. 1290–1343) was a contemporary of William of Ockham who took exception to Occam's razor and Ockham's use of it. In response he devised his own anti-razor: "If three things are not enough to verify an affirmative proposition about things, a fourth must be added and so on." Although there have been several philosophers who have formulated similar anti-razors since Chatton's time, no one anti-razor has perpetuated as notably as Chatton's anti-razor, although this could be the case of the Late Renaissance Italian motto of unknown attribution Se non è vero, è ben trovato ("Even if it is not true, it is well conceived") when referred to a particularly artful explanation.

Anti-razors have also been created by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716), Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), and Karl Menger (1902–1985). Leibniz's version took the form of a principle of plenitude, as Arthur Lovejoy has called it: the idea being that God created the most varied and populous of possible worlds. Kant felt a need to moderate the effects of Occam's razor and thus created his own counter-razor: "The variety of beings should not rashly be diminished."[88]

Karl Menger found mathematicians to be too parsimonious with regard to variables so he formulated his Law Against Miserliness, which took one of two forms: "Entities must not be reduced to the point of inadequacy" and "It is vain to do with fewer what requires more." A less serious but even more extremist anti-razor is 'Pataphysics, the "science of imaginary solutions" developed by Alfred Jarry (1873–1907). Perhaps the ultimate in anti-reductionism, "'Pataphysics seeks no less than to view each event in the universe as completely unique, subject to no laws but its own." Variations on this theme were subsequently explored by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges in his story/mock-essay "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius". Physicist R. V. Jones contrived Crabtree's Bludgeon, which states that "[n]o set of mutually inconsistent observations can exist for which some human intellect cannot conceive a coherent explanation, however complicated."[89]

Recently, American physicist Igor Mazin argued that because high-profile physics journals prefer publications offering exotic and unusual interpretations, the Occam's razor principle is being replaced by an "Inverse Occam's razor", implying that the simplest possible explanation is usually rejected.[90]

Other[edit]

Since 2012 The Skeptic magazine annually awards the Ockham Awards, or simply the Ockhams, named after Occam's razor, at QED.[91] The Ockhams were introduced by editor-in-chief Deborah Hyde to "recognise the effort and time that have gone into the community’s favourite skeptical blogs, skeptical podcasts, skeptical campaigns and outstanding contributors to the skeptical cause."[92] The trophies, designed by Neil Davies and Karl Derrick, carry the upper text "Ockham's" and the lower text "The Skeptic. Shaving away unnecessary assumptions since 1285." Between the texts, there is an image of a double-edged safety razorblade, and both lower corners feature an image of William of Ockham's face.[92]