Nature (philosophy)

Nature has two inter-related meanings in philosophy and natural philosophy. On the one hand, it means the set of all things which are natural, or subject to the normal working of the laws of nature. On the other hand, it means the essential properties and causes of individual things.

Further information: Nature

How to understand the meaning and significance of nature has been a consistent theme of discussion within the history of Western Civilization, in the philosophical fields of metaphysics and epistemology, as well as in theology and science. The study of natural things and the regular laws which seem to govern them, as opposed to discussion about what it means to be natural, is the area of natural science.

The word "nature" derives from Latin nātūra, a philosophical term derived from the verb for birth, which was used as a translation for the earlier (pre-Socratic) Greek term phusis, derived from the verb for natural growth.

Already in classical times, philosophical use of these words combined two related meanings which have in common that they refer to the way in which things happen by themselves, "naturally", without "interference" from human deliberation, divine intervention, or anything outside what is considered normal for the natural things being considered.

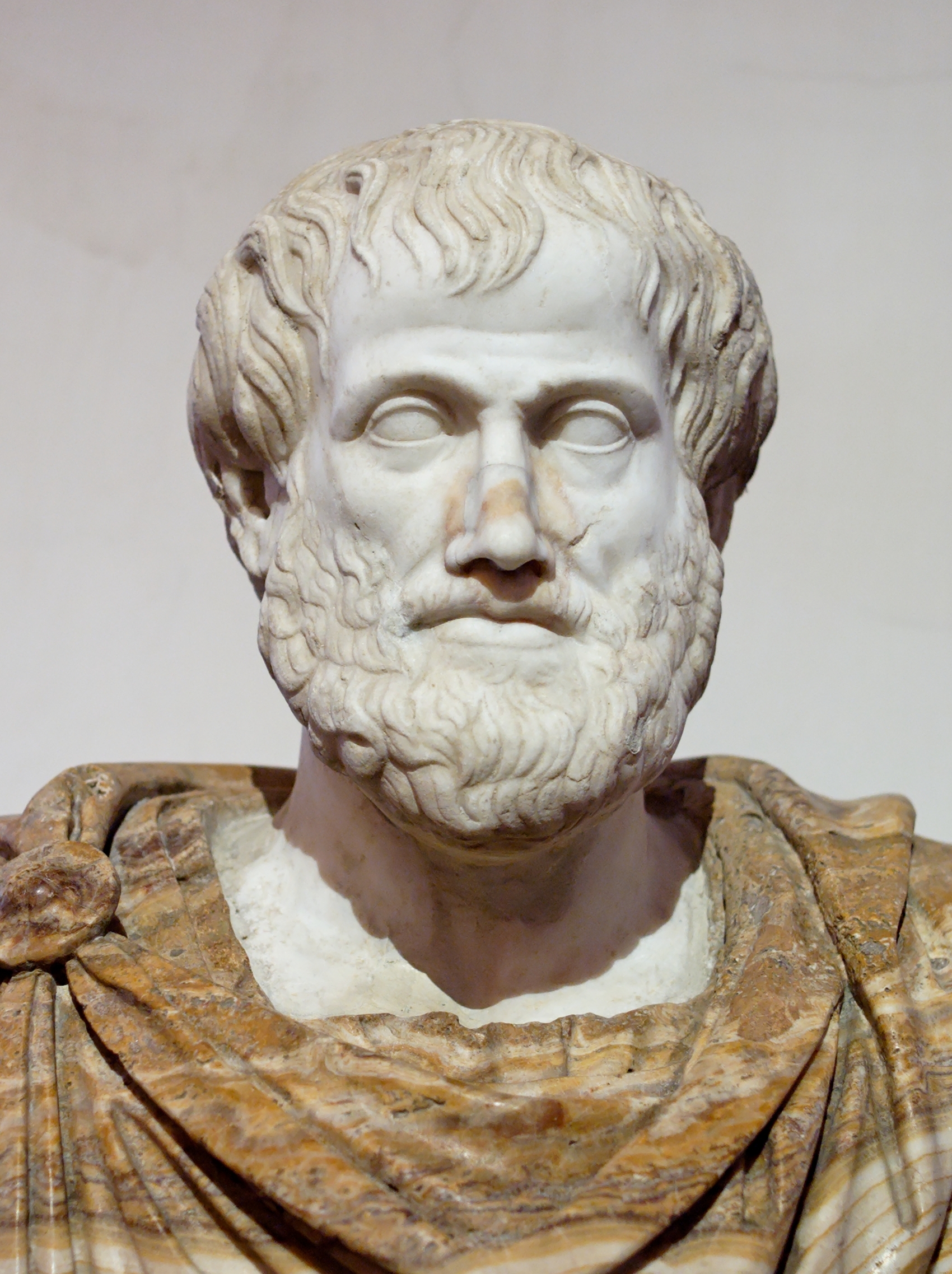

Understandings of nature depend on the subject and age of the work where they appear. For example, Aristotle's explanation of natural properties differs from what is meant by natural properties in modern philosophical and scientific works, which can also differ from other scientific and conventional usage.

The Physics (from ta phusika "the natural [things]") is Aristotle's principal work on nature. In Physics II.1, Aristotle defines a nature as "a source or cause of being moved and of being at rest in that to which it belongs primarily".[1] In other words, a nature is the principle within a natural raw material that is the source of tendencies to change or rest in a particular way unless stopped. For example, a rock would fall unless stopped. Natural things stand in contrast to artifacts, which are formed by human artifice, not because of an innate tendency. (The raw materials of a bed have no tendency to become a bed.) In terms of Aristotle's theory of four causes, the word natural is applied both to the innate potential of matter cause and the forms which the matter tends to become naturally.[2]

According to Leo Strauss,[3] the beginning of Western philosophy involved the "discovery or invention of nature" and the "pre-philosophical equivalent of nature" was supplied by "such notions as 'custom' or 'ways'". In ancient Greek philosophy on the other hand, Nature or natures are ways that are "really universal" "in all times and places". What makes nature different is that it presupposes not only that not all customs and ways are equal, but also that one can "find one's bearings in the cosmos" "on the basis of inquiry" (not for example on the basis of traditions or religion). To put this "discovery or invention" into the traditional terminology, what is "by nature" is contrasted to what is "by convention". The concept of nature taken this far remains a strong tradition in modern Western thinking. Science, according to Strauss' commentary of Western history is the contemplation of nature, while technology was or is an attempt to imitate it.[4]

Going further, the philosophical concept of nature or natures as a special type of causation - for example that the way particular humans are is partly caused by something called "human nature" is an essential step towards Aristotle's teaching concerning causation, which became standard in all Western philosophy until the arrival of modern science.

Whether it was intended or not, Aristotle's inquiries into this subject were long felt to have resolved the discussion about nature in favor of one solution. In this account, there are four different types of cause:

The formal and final cause are an essential part of Aristotle's "Metaphysics" - his attempt to go beyond nature and explain nature itself. In practice they imply a human-like consciousness involved in the causation of all things, even things which are not man-made. Nature itself is attributed with having aims.[6]

The artificial, like the conventional therefore, is within this branch of Western thought, traditionally contrasted with the natural. Technology was contrasted with science, as mentioned above. And another essential aspect to this understanding of causation was the distinction between the accidental properties of a thing and the substance - another distinction which has lost favor in the modern era, after having long been widely accepted in medieval Europe.

To describe it another way, Aristotle treated organisms and other natural wholes as existing at a higher level than mere matter in motion. Aristotle's argument for formal and final causes is related to a doctrine about how it is possible that people know things: "If nothing exists apart from individual things, nothing will be intelligible; everything will be sensible, and there will be no knowledge of anything—unless it be maintained that sense-perception is knowledge".[7] Those philosophers who disagree with this reasoning therefore also see knowledge differently from Aristotle.

Aristotle then, described nature or natures as follows, in a way quite different from modern science:[8]

It has been argued, as will be explained below, that this type of theory represented an oversimplifying diversion from the debates within Classical philosophy, possibly even that Aristotle saw it as a simplification or summary of the debates himself. But in any case the theory of the four causes became a standard part of any advanced education in the Middle Ages.

The study of nature without metaphysics[edit]

Authors from Nietzsche to Richard Rorty have claimed that science, the study of nature, can and should exist without metaphysics. But this claim has always been controversial. Authors like Bacon and Hume never denied that their use of the word "nature" implied metaphysics, but tried to follow Machiavelli's approach of talking about what works, instead of claiming to understand what seems impossible to understand.