Nicomachean Ethics

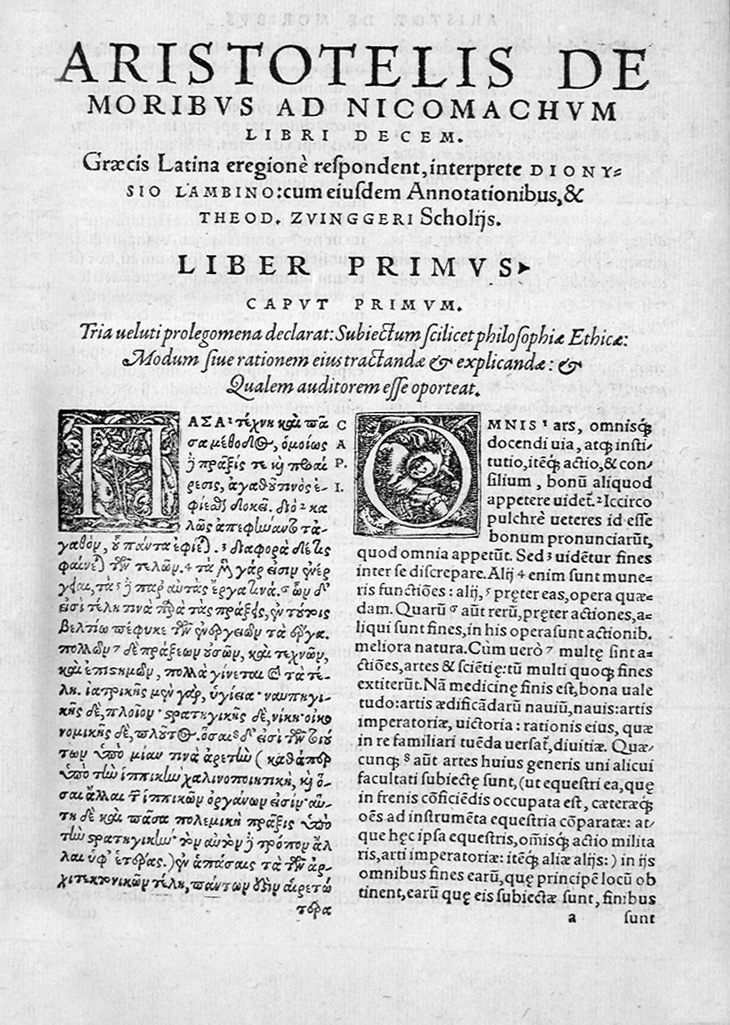

The Nicomachean Ethics (/ˌnaɪkɒməˈkiən, ˌnɪ-/; Ancient Greek: Ἠθικὰ Νικομάχεια, Ēthika Nikomacheia) is among Aristotle's best-known works on ethics: the science of the good for human life, that which is the goal or end at which all our actions aim.[1]: I.2 It consists of ten sections, referred to as books, and is closely related to Aristotle's Eudemian Ethics. The work is essential for the interpretation of Aristotelian ethics.

The text centers around the question of how to best live, a theme previously explored in the works of Plato, Aristotle's friend and teacher. In Aristotle's Metaphysics, he describes how Socrates, the friend and teacher of Plato, turned philosophy to human questions, whereas pre-Socratic philosophy had only been theoretical, and concerned with natural science. Ethics, Aristotle claimed, is practical rather than theoretical, in the Aristotelian senses of these terms. It is not merely an investigation about what good consists of, but it aims to be of practical help in achieving the good.[1]: II.2 (1103b)

It is connected to another of Aristotle's practical works, Politics, which reflects a similar goal: for people to become good, through the creation and maintenance of social institutions. Ethics is about how individuals should best live, while politics adopts the perspective of a law-giver, looking at the good of a whole community.

The Nicomachean Ethics had an important influence on the European Middle Ages, and was one of the core works of medieval philosophy. As such, it was of great significance in the development of all modern philosophy as well as European law and theology. Aristotle became known as "the Philosopher" (for example, this is how he is referred to in the works of Thomas Aquinas). In the Middle Ages, a synthesis between Aristotelian ethics and Christian theology became widespread, as introduced by Albertus Magnus. The most important version of this synthesis was that of Thomas Aquinas. Other more "Averroist" Aristotelians such as Marsilius of Padua were also influential.

Until well into the seventeenth century, the Nicomachean Ethics was still widely regarded as the main authority for the discipline of ethics at Protestant universities, with over fifty Protestant commentaries published before 1682.[2] During the seventeenth century, however, authors such as Francis Bacon and Thomas Hobbes argued that the medieval and Renaissance Aristotelian tradition in practical thinking was impeding philosophy.[3]

Interest in Aristotle's ethics has been renewed by the virtue ethics revival. Recent philosophers in this field include Alasdair MacIntyre, G. E. M. Anscombe, Mortimer Adler, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Martha Nussbaum.

Background[edit]

Parts of the Nicomachean Ethics overlap with Aristotle's Eudemian Ethics:[8] Books V, VI, and VII of the Nicomachean Ethics are identical to Books IV, V, and VI of the Eudemian Ethics. Opinions about the relationship between the two works differ. One suggestion is that three books from Nicomachean Ethics were lost and subsequently replaced by three parallel works from the Eudemian Ethics, which would explain the overlap.[9] Another is that both works were not put into their current form by Aristotle, but by an editor.[10]

No consensus dates the composition of the Nicomachean Ethics. However, a reference in the text to a battle in the Third Sacred War in 353 BCE acts as a terminus post quem for that part of the work.[11] The traditional position, held for example by W. D. Ross,[12] is that the Nicomachean Ethics is a product of the last period of Aristotle's life, during his time in Athens from 335 BCE until his death in 322 BCE.[11]

According to Strabo and Plutarch, after Aristotle's death, his library and writings went to Theophrastus (Aristotle's successor as head of the Lycaeum and the Peripatetic school).[13] After the death of Theophrastus, the library went to Neleus of Scepsis.

The Kingdom of Pergamon conscripted books for a royal library, leading the heirs of Neleus hid their collection in a cellar to prevent its seizure. The library remained there for about a century and a half, in conditions that were not ideal for document preservation. On the death of Attalus III, which also ended the royal library ambitions, the existence of Aristotelian library was disclosed, and it was purchased by Apellicon and returned to Athens in about 100 BCE.

Apellicon sought to recover the texts, many of which were degraded by their time in the cellar. He had them copied into new manuscripts, and used his best guesswork to fill in the gaps where the originals were unreadable.

When Sulla seized Athens in 86 BCE, he seized the library and transferred it to Rome. There, Andronicus of Rhodes organized the texts into the first complete edition of Aristotle's works (and works attributed to him).[14] These relics form the basis of present-day editions, including that of the Nicomachean Ethics.

Aspasius wrote a commentary on the Nicomachean Ethics in the early 2nd century CE. It suggests "that the text [at that time] was very like what it is now, with little or no difference, for instance, of order or arrangement, and with readings identical for the most part with those preserved in one or other of our best [extant manuscripts]." Aspasius noted "the existence of variants—which shows that there was some element of uncertainty as to the text even in this comparatively early stage in the history of the book."[15]

The oldest surviving manuscript is the Codex Laurentianus LXXXI.11 (referred to as "Kb") which dates to the 10th century.

Influence and derivative works[edit]

The Eudemian Ethics is sometimes considered to be a later commentary or paraphrase of the Nicomachean Ethics.[91] The Magna Moralia is usually also interpreted as a post-Aristotle synthesis of Aristotelian Ethics including the Nicomachean and Eudemian, although it is sometimes also attributed to Aristotle.[92]

Parts of a 2nd-century CE commentary about the Nicomachean Ethics by Aspasius exist. This is the earliest extant commentary on any of Aristotle's works, and is notable because Aspasius was a paripatetic, that is, of the Aristotelian scholastic tradition.[93]

Aristotelian ethics was superseded by epicureanism and stoicism in Greek philosophy. In the West it did not regain interest until the 12th century, when the Nicomachean Ethics (and Averroes's 12th-century commentary on it) was rediscovered.[94] Thomas Aquinas called Aristotle "The Philosopher", and published a separate commentary on the Nicomachean Ethics as well as incorporating (or responding to) many of its arguments in his Summa Theologica.

Domenico da Piacenza relied on Aristotle's description of the pleasures of motion in Book X as an authority in his 15th-century treatise on dance principles (one of the earliest written documents on the formal principles of dance that eventually become classical ballet). Da Piacenza, who taught that the ideal smoothness of dance movement could only be attained by a balance of qualities, relied on Aristotelian philosophical concepts of movement, measure, and memory to extol dance on moral grounds, as a virtue.[95]

In G. E. M. Anscombe's 1958 essay "Modern Moral Philosophy", she noted that ethical philosophy had diverged so much since Aristotle that people who use modern ethical notions when discussing Aristotle's ethics "constantly feel like someone whose jaws have somehow got out of alignment: the teeth don't come together in a proper bite". Modern philosophy had, she believed, discarded Aristotle's human telos (and in its skepticism toward divine law as an adequate substitute), and lost a way of making the study of ethics meaningful. As a result, modern moral philosophy was floundering, unable to recall how its intuitions of good and bad could possibly be grounded in facts. She suggested that it might be possible to backtrack and recover an Aristotelian ethics, but that to do this would require updating some of Aristotle's metaphysical and psychological assumptions that are no longer plausible: "philosophically there is a huge gap, at present unfillable as far as we are concerned, which needs to be filled by an account of human nature, human action, the type of characteristic a virtue is, and above all of human 'flourishing.'"[96]

The modern virtue ethics revival has taken up this challenge. Notably, Alasdair MacIntyre in After Virtue (1981) explicitly defended an Aristotelian ethics against modern ethical theories. He claimed that Nietzsche had shown the varieties of modern moral philosophy to be hollow and had effectively refuted them. But he says Nietzsche's refutations do not apply to "the quite distinctive kind of morality" found in Aristotelian ethics. So to recover ethics, "the Aristotelian tradition can be restated in a way that restores intelligibility and rationality to our moral and social attitudes and commitments".[97]