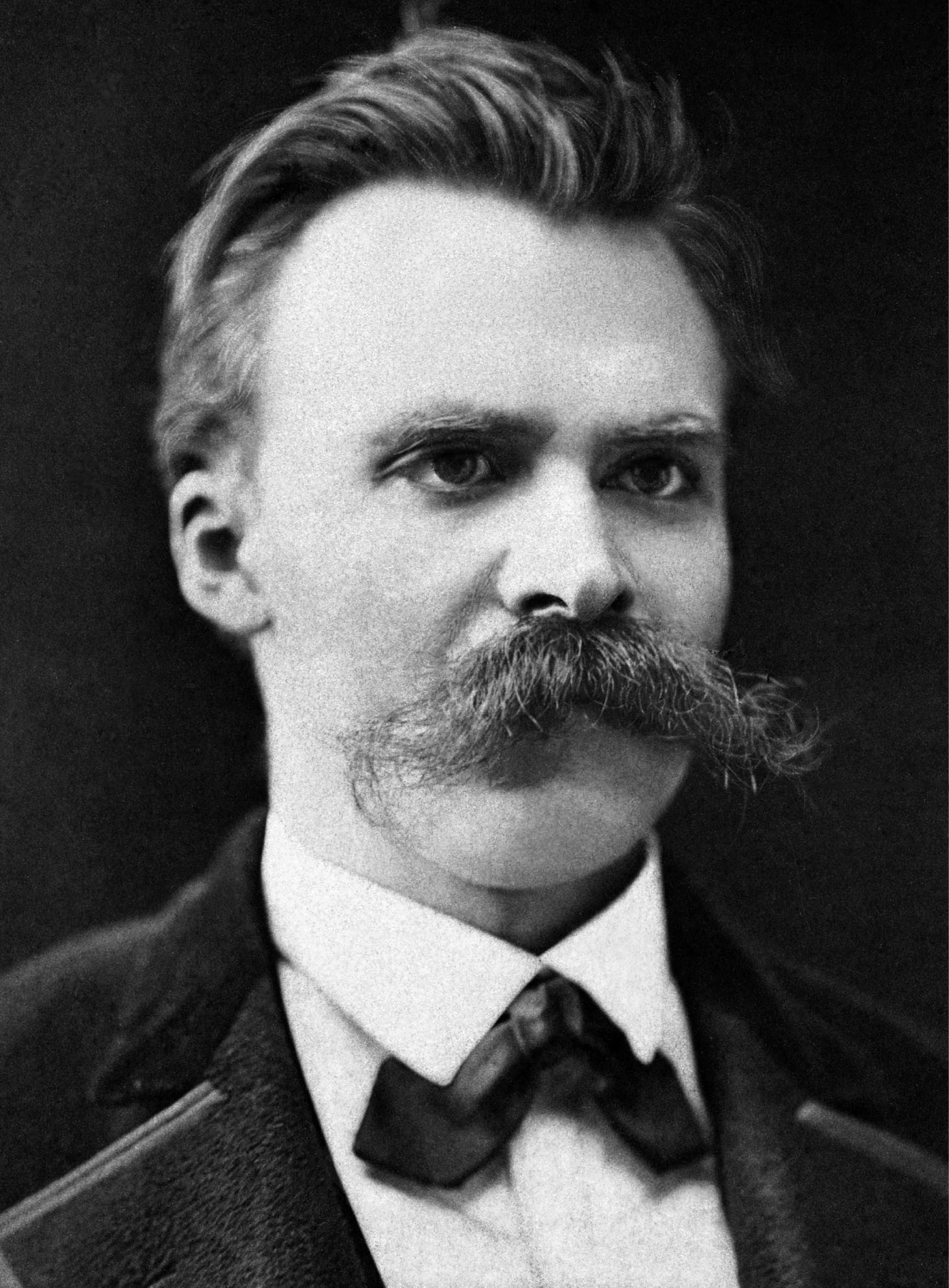

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche[ii] (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philologist before turning to philosophy. He became the youngest person to hold the Chair of Classical Philology at the University of Basel in 1869 at the age of 24, but resigned in 1879 due to health problems that plagued him most of his life; he completed much of his core writing in the following decade. In 1889, at age 44, he suffered a collapse and afterward a complete loss of his mental faculties, with paralysis and probably vascular dementia. He lived his remaining years in the care of his mother until her death in 1897 and then with his sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. Nietzsche died in 1900, after experiencing pneumonia and multiple strokes.

"Nietzsche" redirects here. For other uses, see Nietzsche (disambiguation).

Friedrich Nietzsche

Nietzsche's work spans philosophical polemics, poetry, cultural criticism, and fiction while displaying a fondness for aphorism and irony. Prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical critique of truth in favour of perspectivism; a genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality and a related theory of master–slave morality; the aesthetic affirmation of life in response to both the "death of God" and the profound crisis of nihilism; the notion of Apollonian and Dionysian forces; and a characterisation of the human subject as the expression of competing wills, collectively understood as the will to power. He also developed influential concepts such as the Übermensch and his doctrine of eternal return. In his later work, he became increasingly preoccupied with the creative powers of the individual to overcome cultural and moral mores in pursuit of new values and aesthetic health. His body of work touched a wide range of topics, including art, philology, history, music, religion, tragedy, culture, and science, and drew inspiration from Greek tragedy as well as figures such as Zoroaster, Arthur Schopenhauer, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Richard Wagner, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

After his death, Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth became the curator and editor of his manuscripts. She edited his unpublished writings to fit her German ultranationalist ideology, often contradicting or obfuscating Nietzsche's stated opinions, which were explicitly opposed to antisemitism and nationalism. Through her published editions, Nietzsche's work became associated with fascism and Nazism. 20th-century scholars such as Walter Kaufmann, R. J. Hollingdale, and Georges Bataille defended Nietzsche against this interpretation, and corrected editions of his writings were soon made available. Nietzsche's thought enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1960s and his ideas have since had a profound impact on 20th- and early 21st-century thinkers across philosophy—especially in schools of continental philosophy such as existentialism, postmodernism, and post-structuralism—as well as art, literature, music, poetry, politics, and popular culture.

Life[edit]

Youth (1844–1868)[edit]

Born on 15 October 1844, Nietzsche[14] grew up in the town of Röcken (now part of Lützen), near Leipzig, in the Prussian Province of Saxony. He was named after King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, who turned 49 on the day of Nietzsche's birth (Nietzsche later dropped his middle name Wilhelm).[15] Nietzsche's parents, Carl Ludwig Nietzsche (1813–1849), a Lutheran pastor[16] and former teacher; and Franziska Nietzsche (née Oehler) (1826–1897), married in 1843, the year before their son's birth. They had two other children: a daughter, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, born in 1846; and a second son, Ludwig Joseph, born in 1848. Nietzsche's father died from a brain disease in 1849, after a year of excruciating agony, when the boy was only four years old; Ludwig Joseph died six months later at age two.[17] The family then moved to Naumburg, where they lived with Nietzsche's maternal grandmother and his father's two unmarried sisters. After the death of Nietzsche's grandmother in 1856, the family moved into their own house, now Nietzsche-Haus, a museum and Nietzsche study centre.

A trained philologist, Nietzsche had a thorough knowledge of Greek philosophy. He read Kant, Plato, Mill, Schopenhauer and Spir,[210] who became the main opponents in his philosophy, and later engaged, via the work of Kuno Fischer in particular, with the thought of Baruch Spinoza, whom he saw as his "precursor" in many respects[211][212] but as a personification of the "ascetic ideal" in others. However, Nietzsche referred to Kant as a "moral fanatic", Plato as "boring", Mill as a "blockhead", and of Spinoza, he asked: "How much of personal timidity and vulnerability does this masquerade of a sickly recluse betray?"[213] He likewise expressed contempt for British author George Eliot.[214]

Nietzsche's philosophy, while innovative and revolutionary, was indebted to many predecessors. While at Basel, Nietzsche lectured on pre-Platonic philosophers for several years, and the text of this lecture series has been characterised as a "lost link" in the development of his thought. "In it, concepts such as the will to power, the eternal return of the same, the overman, gay science, self-overcoming and so on receive rough, unnamed formulations and are linked to specific pre-Platonic, especially Heraclitus, who emerges as a pre-Platonic Nietzsche."[215] The pre-Socratic thinker Heraclitus was known for rejecting the concept of being as a constant and eternal principle of the universe and embracing "flux" and incessant change. His symbolism of the world as "child play" marked by amoral spontaneity and lack of definite rules was appreciated by Nietzsche.[216] Due to his Heraclitean sympathies, Nietzsche was also a vociferous critic of Parmenides, who, in contrast to Heraclitus, viewed the world as a single, unchanging Being.[217]

In his Egotism in German Philosophy, George Santayana claimed that Nietzsche's whole philosophy was a reaction to Schopenhauer. Santayana wrote that Nietzsche's work was "an emendation of that of Schopenhauer. The will to live would become the will to dominate; pessimism founded on reflection would become optimism founded on courage; the suspense of the will in contemplation would yield to a more biological account of intelligence and taste; finally in the place of pity and asceticism (Schopenhauer's two principles of morals) Nietzsche would set up the duty of asserting the will at all costs and being cruelly but beautifully strong. These points of difference from Schopenhauer cover the whole philosophy of Nietzsche."[218][219]

The superficial similarity of Nietzsche's Übermensch to Thomas Carlyle's Hero as well as both authors' rhetorical prose style has led to speculation concerning the degree to which Nietzsche might have been influenced by his reading of Carlyle.[220][221][222][223] G. K. Chesterton believed that "Out of [Carlyle] flows most of the philosophy of Nietzsche", qualifying his statement by adding that they were "profoundly different" in character.[224] Ruth apRoberts has shown that Carlyle anticipated Nietzsche in asserting the importance of metaphor (with Nietzsche's metaphor-fiction theory "appear[ing] to owe something to Carlyle"), announcing the death of God, and recognising both Goethe's Entsagen (renunciation) and Novalis's Selbsttödtung (self-annihilation) as prerequisites for engaging in philosophy. apRoberts writes that "Nietzsche and Carlyle had the same German sources, but Nietzsche may owe more to Carlyle than he cares to admit", noting that "[Nietzsche] takes the trouble to repudiate Carlyle with malicious emphasis."[225] Ralph Jessop, senior lecturer at the University of Glasgow, has recently argued that a reassessment of Carlyle's influence on Nietzsche is "long-overdue".[226]

Nietzsche expressed admiration for 17th-century French moralists such as La Rochefoucauld, La Bruyère and Vauvenargues,[227] as well as for Stendhal.[228] The organicism of Paul Bourget influenced Nietzsche,[229] as did that of Rudolf Virchow and Alfred Espinas.[230] In 1867 Nietzsche wrote in a letter that he was trying to improve his German style of writing with the help of Lessing, Lichtenberg and Schopenhauer. It was probably Lichtenberg (along with Paul Rée) whose aphoristic style of writing contributed to Nietzsche's own use of aphorism.[231] Nietzsche early learned of Darwinism through Friedrich Albert Lange.[232] The essays of Ralph Waldo Emerson had a profound influence on Nietzsche, who "loved Emerson from first to last",[233] wrote "Never have I felt so much at home in a book", and called him "[the] author who has been richest in ideas in this century so far".[234] Hippolyte Taine influenced Nietzsche's view on Rousseau and Napoleon.[235] Notably, he also read some of the posthumous works of Charles Baudelaire,[236] Tolstoy's My Religion, Ernest Renan's Life of Jesus, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Demons.[236][237] Nietzsche called Dostoyevsky "the only psychologist from whom I have anything to learn".[238] While Nietzsche never mentions Max Stirner, the similarities in their ideas have prompted a minority of interpreters to suggest a relationship between the two.[239][240][241][242][243][244][245]

In 1861, Nietzsche wrote an enthusiastic essay on his "favorite poet," Friedrich Hölderlin, mostly forgotten at that time.[246] He also expressed deep appreciation for Stifter's Indian Summer,[247] Byron's Manfred and Twain's Tom Sawyer.[248]

A Louis Jacolliot translation of the Calcutta version of the ancient Hindu text called the Manusmriti was reviewed by Friedrich Nietzsche. He commented on it both favourably and unfavorably: