Pipa

The pipa, pípá, or p'i-p'a (Chinese: 琵琶) is a traditional Chinese musical instrument belonging to the plucked category of instruments. Sometimes called the "Chinese lute", the instrument has a pear-shaped wooden body with a varying number of frets ranging from 12 to 31. Another Chinese four-string plucked lute is the liuqin, which looks like a smaller version of the pipa. The pear-shaped instrument may have existed in China as early as the Han dynasty, and although historically the term pipa was once used to refer to a variety of plucked chordophones, its usage since the Song dynasty refers exclusively to the pear-shaped instrument.

This article is about the Chinese instrument. For other uses, see Pipa (disambiguation).Classification

琵琶

pípá

pípa

pípá

pípa

pʻi²-pʻa²

pèih-pàah

pei4-paa4

The pipa is one of the most popular Chinese instruments and has been played for almost two thousand years in China. Several related instruments are derived from the pipa, including the Japanese biwa and Korean bipa in East Asia, and the Vietnamese đàn tỳ bà in Southeast Asia. The Korean instrument is the only one of the three that is no longer widely used.

There are a number of different traditions with different styles of playing pipa in various regions of China, some of which then developed into schools. In the narrative traditions where the pipa is used as an accompaniment to narrative singing, there are the Suzhou tanci (蘇州彈詞), Sichuan qingyin (四川清音), and Northern quyi (北方曲藝) genres. Pipa is also an important component of regional chamber ensemble traditions such as Jiangnan sizhu, Teochew string music and Nanguan ensemble.[50] In Nanguan music, the pipa is still held in the near-horizontal position or guitar-fashion in the ancient manner instead of the vertical position normally used for solo playing in the present day.

There were originally two major schools of pipa during the Qing dynasty—the Northern (Zhili, 直隸派) and Southern (Zhejiang, 浙江派) schools—and from these emerged the five main schools associated with the solo tradition. Each school is associated with one or more collections of pipa music and named after its place of origin:

These schools of the solo tradition emerged by students learning playing the pipa from a master, and each school has its own style, performance aesthetics, notation system, and may differ in their playing techniques.[52][53] Different schools have different repertoire in their music collection, and even though these schools share many of the same pieces in their repertoire, a same piece of music from the different schools may differ in their content. For example, a piece like "The Warlord Takes off His Armour" is made up of many sections, some of them metered and some with free meter, and greater freedom in interpretation is possible in the free meter sections. Different schools however can have sections added or removed, and may differ in the number of sections with free meter.[52] The music collections from the 19th century also used the gongche notation which provides only a skeletal melody and approximate rhythms sometimes with the occasional playing instructions given (such as tremolo or string-bending), and how this basic framework can become fully fleshed out during a performance may only be learnt by the students from the master. The same piece of music can therefore differ significantly when performed by students of different schools, with striking differences in interpretation, phrasing, tempo, dynamics, playing techniques, and ornamentations.

In more recent times, many pipa players, especially the younger ones, no longer identify themselves with any specific school. Modern notation systems, new compositions as well as recordings are now widely available and it is no longer crucial for a pipa players to learn from the master of any particular school to know how to play a score.

Use in other genres[edit]

The pipa has also been used in rock music; the California-based band Incubus featured one, borrowed from guitarist Steve Vai, in their 2001 song "Aqueous Transmission," as played by the group's guitarist, Mike Einziger.[69] The Shanghai progressive/folk-rock band Cold Fairyland, which was formed in 2001, also use pipa (played by Lin Di), sometimes multi-tracking it in their recordings. Australian dark rock band The Eternal use the pipa in their song "Blood" as played by singer/guitarist Mark Kelson on their album Kartika. The artist Yang Jing plays pipa with a variety of groups.[70] The instrument is also played by musician Min Xiaofen in "I See Who You Are", a song from Björk's album Volta. Western performers of pipa include French musician Djang San, who integrated jazz and rock concepts to the instrument such as power chords and walking bass.[71]

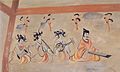

![An apsara (feitian) playing pipa, using fingers with the pipa held in near upright position. Mural from Kizil, estimated Five Dynasties to Yuan dynasty, 10th to 13th century.[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/Pipa_player_from_Kizil.jpg/117px-Pipa_player_from_Kizil.jpg)