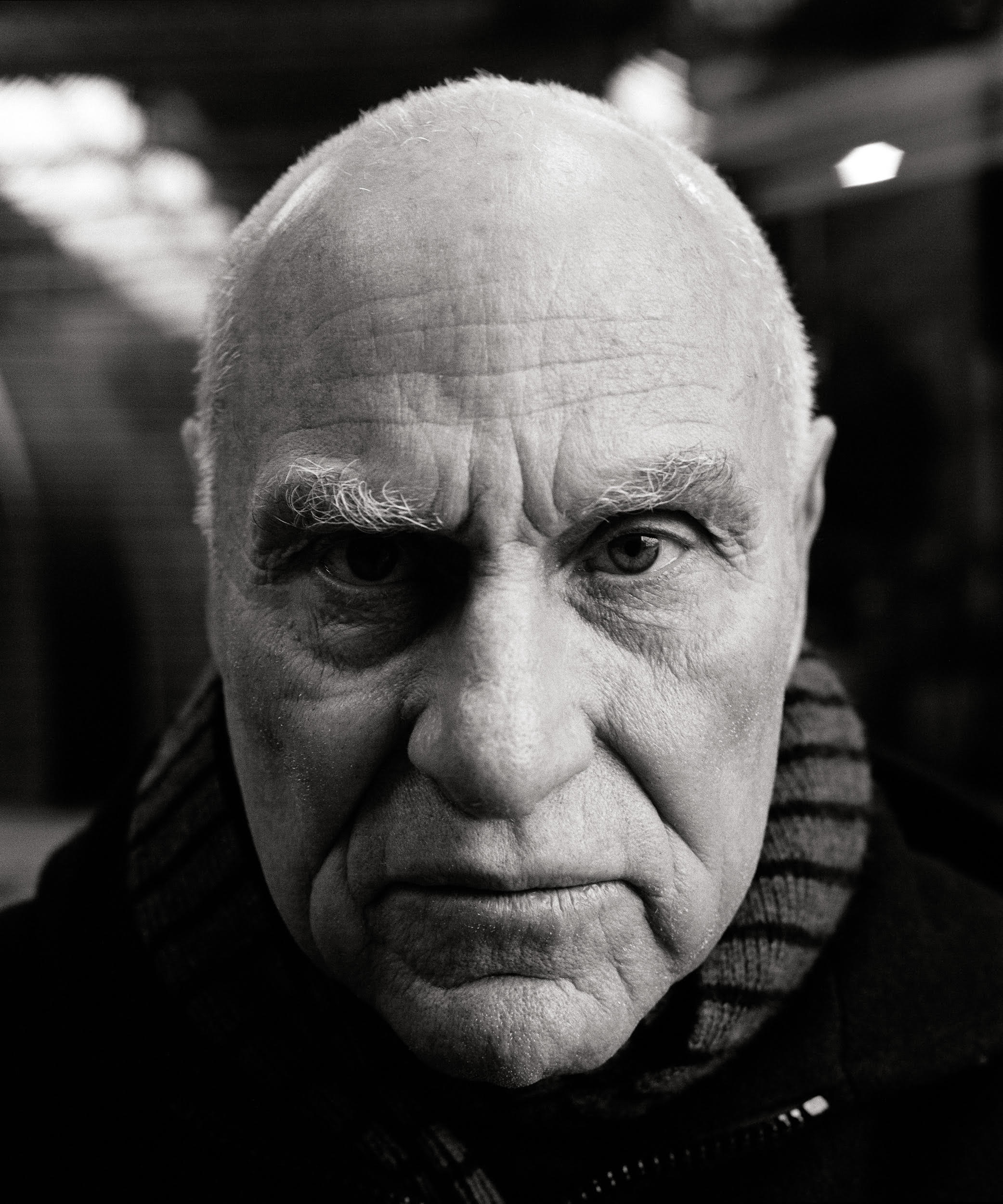

Richard Serra

Richard Serra (November 2, 1938 – March 26, 2024) was an American artist known for his large-scale abstract sculptures made for site-specific landscape, urban, and architectural settings, whose work has been primarily associated with Postminimalism. Described as "one of his era's greatest sculptors", Serra became notable for emphasizing the material qualities of his works and exploration of the relationship between the viewer, the work, and the site.[1]

Richard Serra

November 2, 1938

March 26, 2024 (aged 85)

American

University of California, Berkeley (attended)

University of California, Santa Barbara (B.A. 1961)

Yale University (B.F.A. 1962, M.F.A. 1964)

Serra pursued English literature at the University of California, Berkeley, before shifting to visual art. He graduated with a B.A. in English Literature from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1961, where he met influential muralists Rico Lebrun and Howard Warshaw. Supporting himself by working in steel mills, Serra's early exposure to industrial materials influenced his artistic trajectory. He continued his education at Yale University, earning a B.A. in Art History and an M.F.A. in 1964. While in Paris on a Yale fellowship in 1964, he befriended composer Philip Glass and explored Constantin Brâncuși's studio, both of which had a strong influence on his work. His time in Europe also catalyzed his subsequent shift from painting to sculpture.

From the mid-1960s onward, particularly after his move to New York City in 1966, Serra worked to radicalize and extend the definition of sculpture beginning with his early experiments with rubber, neon, and lead, to his large-scale steel works. His early works in New York, such as To Lift from 1967 and Thirty-Five Feet of Lead Rolled Up from 1968, reflected his fascination with industrial materials and the physical properties of his chosen mediums. His large-scale works, both in urban and natural landscapes, have reshaped public interactions with art and, at times, were also a source of controversy, such as that caused by his Tilted Arc in Manhattan in 1981. Serra was married to artist Nancy Graves between 1965 and 1970, and Clara Weyegraf between 1981 and his death in 2024.

Early life and education[edit]

Serra was born in San Francisco, California, on November 2, 1938,[2][3] to Tony and Gladys Serra – the second of three sons.[4] His father was Spanish from Mallorca and his mother Gladys was the daughter of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants from Odessa.[2][5] From a young age, he was encouraged to draw by his mother. The young Serra would carry a small notebook for his sketches and his mother would introduce her son as "Richard the artist."[6] His father worked as a pipe fitter for a shipyard near San Francisco.[7][8] Serra recounted a memory of a visit to the shipyard to see a boat launch when he was four years old.[9] He watched as the ship transformed from an enormous weight to a buoyant, floating structure and noted that: "All the raw material that I needed is contained in the reserve of this memory."[10] Serra's father, who was related to the Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí, later worked as a candy plant foreman.[11]

Serra studied English literature at the University of California, Berkeley in 1957[12] before transferring to the University of California, Santa Barbara and graduating in 1961 with a BA in English Literature. In Santa Barbara, Serra met the muralists, Rico Lebrun and Howard Warshaw. Both were in the Art Department and took Serra under their wing.[13] During this period, Serra worked in steel mills to earn a living, as he did at various times from ages 16–25.[14]

Serra studied painting at Yale University and graduated with both a BA in Art History and an MFA in 1964. Fellow Yale alumni contemporaneous to Serra include Chuck Close, Rackstraw Downs, Nancy Graves, Brice Marden, and Robert Mangold.[15] At Yale Serra met visiting artists from the New York School such as Philip Guston, Robert Rauschenberg, Ad Reinhardt, and Frank Stella. Serra taught a color theory course during his last year at Yale and after graduating was asked to help proof Josef Albers' notable color theory book "Interaction of Color."[15][16]

In 1964, Serra was awarded a one-year traveling fellowship from Yale and went to Paris where he met the composer Philip Glass[15] who became a collaborator and long-time friend. In Paris, Serra spent time sketching in Constantin Brâncuși's studio, partially reconstructed inside the Musée national d'Art moderne on the Avenue du Président Wilson,[15] allowing Serra to study Brâncuși's work, later drawing his own sculptural conclusions.[17] An exact replica of Brâncuși's studio is now located opposite the Centre Pompidou.[18] Serra spent the following year in Florence, Italy on a Fulbright Grant. In 1966 while still in Italy, Serra made a trip to the Prado Museum in Spain and saw Diego Velázquez's painting, "Las Meninas."[18] The artist realized he would not surpass the skill of that painting and made the decision to move away from painting.[6]

While still in Europe, Serra began experimenting with nontraditional sculptural material. He had his first one-person exhibition "Animal Habitats" at Galleria Salita, Rome.[19] Exhibited there were assemblages made with live and stuffed animals which would later be referenced as early work from the Arte Povera movement.[10]

Work[edit]

Early work[edit]

Serra returned from Europe and moved to New York City in 1966. He continued his constructions using experimental materials such as rubber, latex, fiberglass, neon, and lead.[20] His Belt Pieces were made with strips of rubber and hung on the wall using gravity as a forming device. Serra combined neon with continuous strips of rubber in his sculpture Belts (1966–67) referencing the serial abstraction in Jackson Pollock's Mural (1963.) Around that time Serra wrote Verb List (1967) a list of transitive verbs (i.e. cast, roll, tear, prop, etc.) which he used as directives for his sculptures.[21] To Lift (1967), and Thirty-Five Feet of Lead Rolled Up (1968), Splash Piece (1968), and Casting (1969), were some of the action-based works with origins in the verb list. Serra used lead in many of his constructs because of its adaptability. Lead is malleable enough to be rolled, folded, ripped, and melted. With To Lift (1967) Serra lifted a 10-foot (3 m) sheet of rubber off the ground making a free-standing form; with Thirty-five Feet of Lead Rolled Up (1968), Serra, with the help of Philip Glass, unrolled and rolled a sheet of lead as tightly as they could.[21]

In 1968 Serra was included in the group exhibition "Nine at Castelli" at Castelli Warehouse in New York[22] where he showed Prop (1968), Scatter Piece (1968), and made Splashing (1968) by throwing molten lead against the angle of the floor and wall. In 1969 his piece Casting was included in the exhibition Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.[22] In Casting the artist again threw molten lead against the angle of the floor and wall. He then pulled the casting made from the hardened lead away from the wall and repeated the action of splashing and casting creating a series of free-standing forms.[23]

"To prop" is another transitive verb from Serra's "Verb List" utilized by the artist for a series assemblages of lead plates and poles dependent on leaning and gravity as a force to stay upright.[23] Serra's early Prop Pieces such as Prop (1968) relied mainly on the wall as a support.[24] Serra wanted to move away from the wall to remove what he thought was a pictorial convention. In 1969 he propped four lead plates up on the floor like a house of cards. The sculpture One Ton Prop: House of Cards (1969) weighed 1 ton and the four plates were self-supporting.[25]

Another pivotal moment for Serra occurred in 1969 when he was commissioned by the artist Jasper Johns to make a Splash Piece in Johns's studio. While Serra heated the lead plates to splash against the wall, he took one of the larger plates and set it in the corner where it stood on its own. Serra's break into space followed shortly after with the sculpture Strike: To Roberta and Rudy (1969–71).[26] Serra wedged an 8 by 24-foot (2.4 × 7.3 m) plate of steel into a corner and divided the room into two equal spaces. The work invited the viewer to walk around the sculpture, shifting the viewer's perception of the room as they walked.[23]

Serra first recognized the potential of working in large scale with his Skullcracker Series made during the exhibition, "Art and Technology," at LACMA (the Los Angelos County Museum of Art) in 1969. He spent ten weeks building a number of ephemeral stacked steel pieces at the Kaiser Steelyard. Using a crane to explore the principles of counterbalance and gravity, the stacks were as tall as 30 to 40 feet (9 to 12 m) high and weighed between 60 and 70 tons (54.4 and 63.5 t). They were knocked down by the steel workers at the end of each day. The scale of the stacks allowed Serra to begin to think of his work outside the confines of gallery and museum spaces.[27]

Exhibitions[edit]

Serra's first solo exhibition was in 1966 at Galleria Salita in Rome, Italy.[87] His first solo exhibition in the U.S. was at the Leo Castelli Warehouse, New York in 1969.[88] His first solo museum exhibition was held at the Pasadena Art Museum in California in 1970.[89]

The first retrospective of his work was held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1986.[90] A second retrospective was held at The Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2007.[91]

The first survey exhibition of his drawings was held at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in 1977 and traveled to the Kunsthalle Tübingen in 1978. A second retrospective of drawings was presented at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City; the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; and The Menil Collection, Houston from 2011 to 2012.[92] An overview of the artist's work in film and video was on view at the Kunstmuseum Basel, in 2017.[93]

Serra enjoyed solo exhibitions at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, 1978; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, 1980; Musée National d'Art Moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 1983–1984; Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, 1985; The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1986 and 2007; Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, 1986; Westphalian State Museum of Art and Cultural History, Münster, 1987; Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, 1987; Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, 1988; Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, 1990; Kunsthaus Zürich, 1990; CAPC Musée d'Art Contemporain, Bordeaux, 1990; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, 1992; Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, 1992; Dia Center for the Arts, New York, 1997; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, 1998–1999; Centro de Arte Hélio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro, 1997–1998; Trajan's Market, Rome, 1999–2000; Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts, St. Louis, 2003; National Archaeological Museum, Naples, 2004; and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, in 2017.[94][95]

Collections[edit]

Serra's work is included in many museums and public collections around the world. Selected museum collections which own his work include The Museum of Modern Art, New York; The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Art Institute of Chicago; Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Centre Cultural Fundació La Caixa, Barcelona; Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas; Dia Art Foundation, New York; Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and New York; Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Moderna Museet, Stockholm; and Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland.[96]

Selected public collections which hold his work include City of Bochum, Germany; City of Chicago, Public Art Collection; City of Goslar, Germany; City of Hamburg, Germany; City of St. Louis, Missouri; City of Tokyo, Japan; City of Berlin, Germany; City of Paris, France; Collection City of Reykjavík, Iceland.[96]

Personal life[edit]

Richard Serra moved to New York City in 1966. He bought a house in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, in 1970 and spent summers working there. Serra married art historian Clara Weyergraf in 1981.[97] As of 2019, Serra maintained a home in Manhattan and studios in Nova Scotia and the North Fork of Long Island.[98]

Serra died from pneumonia at his home in Orient, New York, on March 26, 2024, at the age of 85.[3][99][100][101]

Awards[edit]

Serra was the recipient of many notable prizes and awards, including Fulbright Grant (1965–66); Guggenheim Fellowship (1970); République Française, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (1985 and 1991); Japan Arts Association, Tokyo Praemium Imperiale (1994); a Leone d'Oro for lifetime achievement, Venice Biennale, Italy (2001); American Academy of Arts and Letters (2001); Orden pour le Mérite für Wissenschaften und Künste, Federal Republic of Germany (2002); Orden de las Artes y las Letras de España, Spain (2008); The National Arts Award: Lifetime Achievement Award (bestowed by Americans for the Arts 2014); Hermitage Museum Foundation's Award for Lifetime Contributions to the World of Art (2014); Chevalier de l'Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur, Republic of France (2015); Landesmuseum Wiesbaden Alexej-von-Jawlensky-Preis (2017); and a J. Paul Getty Medal (2018).[96]

Gathered in the following three anthologies is a comprehensive collection of writings by, and interviews with, the artist:

Actor[edit]

Serra plays an architect who is a third level Mason in artist and filmmaker Matthew Barney's Cremaster 3 from the director's five-part Cremaster Cycle.[102]

All solely by Richard Serra unless indicated otherwise.