Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau (/ˌɑːr(t) nuːˈvoʊ/ AR(T) noo-VOH, French: [aʁ nuvo] ⓘ; lit. 'New Art') is an international style of art, architecture, and applied art, especially the decorative arts. It was often inspired by natural forms such as the sinuous curves of plants and flowers.[1] Other characteristics of Art Nouveau were a sense of dynamism and movement, often given by asymmetry or whiplash lines, and the use of modern materials, particularly iron, glass, ceramics and later concrete, to create unusual forms and larger open spaces.[2] It was popular between 1890 and 1910 during the Belle Époque period,[3] and was a reaction against the academicism, eclecticism and historicism of 19th century architecture and decorative art.

Years active

c. 1883–1914

One major objective of Art Nouveau was to break down the traditional distinction between fine arts (especially painting and sculpture) and applied arts. It was most widely used in interior design, graphic arts, furniture, glass art, textiles, ceramics, jewellery and metal work. The style responded to leading 19-century theoreticians, such as French architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814–1879) and British art critic John Ruskin (1819–1900). In Britain, it was influenced by William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. German architects and designers sought a spiritually uplifting Gesamtkunstwerk ('total work of art') that would unify the architecture, furnishings, and art in the interior in a common style, to uplift and inspire the residents.[2]

The first Art Nouveau houses and interior decoration appeared in Brussels in the 1890s, in the architecture and interior design of houses designed by Paul Hankar, Henry van de Velde, and especially Victor Horta, whose Hôtel Tassel was completed in 1893.[4][5][6] It moved quickly to Paris, where it was adapted by Hector Guimard, who saw Horta's work in Brussels and applied the style to the entrances of the new Paris Métro. It reached its peak at the 1900 Paris International Exposition, which introduced the Art Nouveau work of artists such as Louis Tiffany. It appeared in graphic arts in the posters of Alphonse Mucha, and the glassware of René Lalique and Émile Gallé.

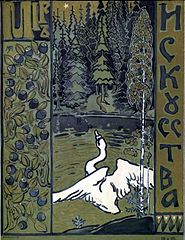

From Britain, Belgium and France, Art Nouveau spread to the rest of Europe, taking on different names and characteristics in each country (see Naming section below). It often appeared not only in capitals, but also in rapidly growing cities that wanted to establish artistic identities (Turin and Palermo in Italy; Glasgow in Scotland; Munich and Darmstadt in Germany; Barcelona in Catalonia, Spain), as well as in centres of independence movements (Helsinki in Finland, then part of the Russian Empire).

By 1914, with the beginning of the First World War, Art Nouveau was largely exhausted. In the 1920s, it was replaced as the dominant architectural and decorative art style by Art Deco and then Modernism.[7] The Art Nouveau style began to receive more positive attention from critics in the late 1960s, with a major exhibition of the work of Hector Guimard at the Museum of Modern Art in 1970.[8]

The term Art Nouveau was first used in the 1880s in the Belgian journal L'Art Moderne to describe the work of Les Vingt, twenty painters and sculptors seeking reform through art. The name was popularized by the Maison de l'Art Nouveau ('House of the New Art'), an art gallery opened in Paris in 1895 by the Franco-German art dealer Siegfried Bing. In Britain, the French term Art Nouveau was commonly used, while in France, it was often called by the term Style moderne (akin to the British term Modern Style), or Style 1900.[9] In France, it was also sometimes called Style Jules Verne (after the novelist Jules Verne), Style Métro (after Hector Guimard's iron and glass subway entrances), Art Belle Époque, or Art fin de siècle.[10]

Art Nouveau is known by different names in different languages: Jugendstil in German, Stile Liberty in Italian, Modernisme in Catalan, and also known as the Modern Style in English. The style is often related to, but not always identical with, styles that emerged in many countries in Europe and elsewhere at about the same time. Their local names were often used in their respective countries to describe the whole movement.

Early Art Nouveau, particularly in Belgium and France, was characterized by undulating, curving forms inspired by lilies, vines, flower stems and other natural forms, used in particular in the interiors of Victor Horta and the decoration of Louis Majorelle and Émile Gallé.[171] It also drew upon patterns based on butterflies and dragonflies, borrowed from Japanese art, which were popular in Europe at the time.[171]

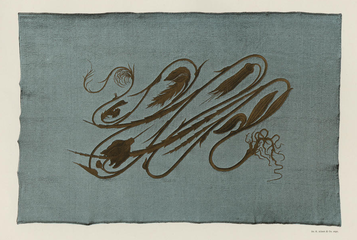

Early Art Nouveau also often featured more stylized forms expressing movement, such as the coup de fouet or "whiplash" line, depicted in the cyclamen plants drawn by designer Hermann Obrist in 1894. A description published in Pan magazine of Hermann Obrist's wall hanging Cyclamen (1894), compared it to the "sudden violent curves generated by the crack of a whip,"[172] The term "whiplash", though it was originally used to ridicule the style, is frequently applied to the characteristic curves employed by Art Nouveau artists.[172] Such decorative undulating and flowing lines in a syncopated rhythm and asymmetrical shape, are often found in the architecture, painting, sculpture, and other forms of Art Nouveau design.[172]

Other floral forms were popular, inspired by lilies, wisteria and other flowers, particularly in the lamps of Louis Comfort Tiffany and the glass objects made by the artists of the School of Nancy and Émile Gallé. Other curving and undulating forms borrowed from nature included butterflies, peacocks, swans, and water lilies. Many designs depicted women's hair intertwined with stems of lilies, irises and other flowers.[173] Stylized floral forms were particularly used by Victor Horta in carpets, balustrades, windows, and furniture. They were also used extensively by Hector Guimard for balustrades, and, most famously, for the lamps and railings at the entrances of the Paris Metro. Guimard explained: "That which must be avoided in everything that is continuous is the parallel and symmetry. Nature is the greatest builder and nature makes nothing that is parallel and nothing that is symmetrical."[174]

Earlier Art Nouveau furniture, such as that made by Louis Majorelle and Henry van de Velde, was characterized by the use of exotic and expensive materials, including mahogany with inlays of precious woods and trim, and curving forms without right angles. It gave a sensation of lightness.

In the second phase of Art Nouveau, following 1900, the decoration became purer and the lines were more stylized. The curving lines and forms evolved into polygons and then into cubes and other geometric forms. These geometric forms were used with particular effect in the architecture and furniture of Joseph Maria Olbrich, Otto Wagner, Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, especially the Stoclet Palace in Brussels, which announced the arrival of Art Deco and modernism.[88][89][90]

Another characteristic of Art Nouveau architecture was the use of light, by opening up of interior spaces, by the removal of walls, and the extensive use of skylights to bring a maximum amount of light into the interior. Victor Horta's residence-studio and other houses built by him had extensive skylights, supported on curving iron frames. In the Hotel Tassel he removed the traditional walls around the stairway, so that the stairs became a central element of the interior design.

As an art style, Art Nouveau has affinities with the Pre-Raphaelites and the Symbolist styles, and artists like Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Edward Burne-Jones, Gustav Klimt and Jan Toorop could be classed in more than one of these styles. Unlike Symbolist painting, however, Art Nouveau has a distinctive appearance; and, unlike the artisan-oriented Arts and Crafts movement, Art Nouveau artists readily used new materials, machined surfaces, and abstraction in the service of pure design.

Art Nouveau did not eschew the use of machines, as the Arts and Crafts movement did. For sculpture, the principal materials employed were glass and wrought iron, resulting in sculptural qualities even in architecture. Ceramics were also employed in creating editions of sculptures by artists such as Auguste Rodin.[177] though his sculpture is not considered Art Nouveau.

Art Nouveau architecture made use of many technological innovations of the late 19th century, especially the use of exposed iron and large, irregularly shaped pieces of glass for architecture.

Art Nouveau tendencies were also absorbed into local styles. In Denmark, for example, it was one aspect of Skønvirke ('Aesthetic work'), which itself more closely relates to the Arts and Crafts style.[178][179] Likewise, artists adopted many of the floral and organic motifs of Art Nouveau into the Młoda Polska ('Young Poland') style in Poland.[180] Młoda Polska, however, was also inclusive of other artistic styles and encompassed a broader approach to art, literature, and lifestyle.[181]

Architecturally, Art Nouveau has affinities with styles that, although modern, exist outside the modernist tradition established by architects like Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier. It is particularly closely related to Expressionist architecture, which shares its preference for organic shapes, but grew out of an intellectual dissatisfaction with Art Nouveau's approach to ornamentation. As opposed to Art Nouveau's focus on plants and vegetal motifs, Expressionism takes inspiration from things like caves, mountains, lightning, crystal, and rock formations.[182] Another style conceived as a reaction to Art Nouveau was Art Deco, which rejected organic surfaces altogether in preference for a rectilinear style derived from the contemporary artistic avant-garde.

There are 4 types of museums featuring Art Nouveau heritage:

There are many other Art Nouveau buildings and structures that do not have museum status but can be officially visited for a fee or unofficially for free (e.g. railway stations, churches, cafes, restaurants, pubs, hotels, stores, offices, libraries, cemeteries, fountains as well as numerous apartment buildings that are still inhabited).

![Doorway of the Lavirotte Building, with ceramic sculptures by Jean-Baptiste Larrivé [fr]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/47/XDSC_7288-29-av-Rapp-paris-7.jpg/176px-XDSC_7288-29-av-Rapp-paris-7.jpg)

![Decorative stylized lettering – Grave of the Caillat Family in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, by Guimard (1899)[169]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d7/P%C3%A8re-Lachaise_-_Division_2_-_Ernest_Caillat_01_%28cropped%29.jpg/172px-P%C3%A8re-Lachaise_-_Division_2_-_Ernest_Caillat_01_%28cropped%29.jpg)

![Nymphs – Relief on the Fanny and Isac Popper House (Strada Sfinților no. 1), Bucharest, by Alfred Popper (1914)[170]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f5/1_Strada_Sfin%C8%9Bilor%2C_Bucharest_%2803%29.jpg/181px-1_Strada_Sfin%C8%9Bilor%2C_Bucharest_%2803%29.jpg)

![Mix of Art Nouveau and Gothic Revival – Rue Gustave-Lemaire no. 51 in Dunkerque, France, with pointed arched-dormer windows and balcony loggia, unknown architect, decorated with sculptures by Maurice Ringot (1903–1910)[175]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/51_rue_Gustave_Lemaire.jpg/225px-51_rue_Gustave_Lemaire.jpg)

![Mix of Art Nouveau and Egyptian Revival – Round corner window of the Romulus Porescu House (Strada Doctor Paleologu no. 12) in Bucharest, decorated with lotus flowers, a motif used frequently in Ancient Egyptian art, designed by Dimitrie Maimarolu (1905)[176]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Negustori_col%C8%9B_cu_Paleologu._-streetphotography_-bucharest_-windows_-rusty_-old_%2834264373636%29.jpg/300px-Negustori_col%C8%9B_cu_Paleologu._-streetphotography_-bucharest_-windows_-rusty_-old_%2834264373636%29.jpg)

![Entry for the House for an art lover competition, by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1900)[229]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/15/Mackintosh%2C_House_for_an_Art_Lover%2C_competition_entry.jpg/342px-Mackintosh%2C_House_for_an_Art_Lover%2C_competition_entry.jpg)

![Secessionist exterior of the Bazil Assan House (Strada Scaune no. 21–23, currently Strada Tudor Arghezi) in Bucharest, by Marcel Kammerer (1902–1911), demolished in the late 1950s or the 1960s to make space for the National Theatre Bucharest[230]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ad/Main_view_of_the_Bazil_Assan_House_in_Bucharest.jpg/353px-Main_view_of_the_Bazil_Assan_House_in_Bucharest.jpg)

![Secessionist façade of the Stoclet Palace in Brussels, by Josef Hoffmann (1905–1911)[231]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Bruxelles_-_Palais_Stoclet_%283%29_%28cropped_center%29.jpg/156px-Bruxelles_-_Palais_Stoclet_%283%29_%28cropped_center%29.jpg)

![Secessionist putto with two cornucopias with floral cascades, very similar to the ones found in a lot of Art Deco of the 1910s and 1920s, by Michael Powolny, designed in c. 1907, produced in 1912, ceramic, Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin[232]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/Michael_powolny_e_bertold_l%C3%B6ffler%2C_putto_con_cornucopia%2C_vienna_1912_ca.jpg/209px-Michael_powolny_e_bertold_l%C3%B6ffler%2C_putto_con_cornucopia%2C_vienna_1912_ca.jpg)

![Sinuous curves on the façade of Avenue Montaigne no. 26 in Paris, by Louis Duhayon and Marcel Julien (1937)[233]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Avenue_Montaigne_%2847128639262%29.jpg/383px-Avenue_Montaigne_%2847128639262%29.jpg)