Sino-Indian War

The Sino–Indian War, also known as the China–India War or the Indo–China War, was an armed conflict between China and India that took place from October to November 1962. It was a military escalation of the Sino–Indian border dispute. Fighting occurred along India's border with China, in India's North-East Frontier Agency east of Bhutan, and in Aksai Chin west of Nepal.

"Indo-Chinese War" redirects here. For the war in the area named Indochina, see Indochina War and Indochina Wars. For clashes on the Sino-Indian border in 1967, see Nathu La and Cho La clashes. For the recent border dispute between China and India, see 2020–2021 China–India skirmishes.

There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tibetan uprising, when India granted asylum to the Dalai Lama. Chinese military action grew increasingly aggressive after India rejected proposed Chinese diplomatic settlements throughout 1960–1962, with China resuming previously banned "forward patrols" in Ladakh after 30 April 1962.[8][9] Amidst the Cuban Missile Crisis, China abandoned all attempts towards a peaceful resolution on 20 October 1962,[10] invading disputed territory along the 3,225-kilometre (2,004 mi) border in Ladakh and across the McMahon Line in the northeastern frontier. Chinese troops pushed Indian forces back in both theatres, capturing all of their claimed territory in the western theatre and the Tawang Tract in the eastern theatre. The conflict ended when China unilaterally declared a ceasefire on 20 November 1962, and simultaneously announced its withdrawal to its pre-war position, the effective China–India border (also known as the Line of Actual Control).

Much of the fighting comprised mountain warfare, entailing large-scale combat at altitudes of over 4,000 metres (13,000 feet). Notably, the war took place entirely on land, without the use of naval or air assets by either side.

As the Sino-Soviet split deepened, the Soviet Union made a major effort to support India, especially with the sale of advanced MiG fighter aircraft. Simultaneously, the United States and the United Kingdom refused to sell advanced weaponry to India, further compelling it to turn to the Soviets for military aid.[11][12]

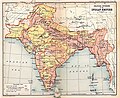

China and India shared a long border, sectioned into three stretches by Nepal, Sikkim (then an Indian protectorate), and Bhutan, which follows the Himalayas between Burma and what was then West Pakistan. A number of disputed regions lie along this border. At its western end is the Aksai Chin region, an area the size of Switzerland, that sits between the Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang and Tibet, which China declared as an autonomous region in 1965. The eastern border, between Burma and Bhutan, comprises the present Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, formerly the North-East Frontier Agency. Both of these regions were overrun by China in the 1962 conflict.

Most combat took place at high elevations. The Aksai Chin region is a desert of salt flats around 5,000 metres (16,000 feet) above sea level, and Arunachal Pradesh is mountainous with a number of peaks exceeding 7,000 metres (23,000 feet). The Chinese Army had possession of one of the highest ridges in the regions. The high altitude and freezing conditions caused logistical and welfare difficulties. In past similar conflicts, such as the Italian Campaign of World War I, harsh conditions have caused more casualties than have enemy actions. The Sino-Indian War was no different, with many troops on both sides succumbing to the freezing cold temperatures.[13]

Chinese preparations

Chinese motives

Two of the major factors leading up to China's eventual conflicts with Indian troops were India's stance on the disputed borders and perceived Indian subversion in Tibet. There was "a perceived need to punish and end perceived Indian efforts to undermine Chinese control of Tibet, Indian efforts which were perceived as having the objective of restoring the pre-1949 status quo ante of Tibet". The other was "a perceived need to punish and end perceived Indian aggression against Chinese territory along the border". John W. Garver argues that the first perception was incorrect based on the state of the Indian military and polity in the 1960s. It was, nevertheless a major reason for China's going to war. He argues that while the Chinese perception of Indian border actions were "substantially accurate", Chinese perceptions of the supposed Indian policy towards Tibet were "substantially inaccurate".[37]

The CIA's declassified POLO documents reveal contemporary American analysis of Chinese motives during the war. According to this document, "Chinese apparently were motivated to attack by one primary consideration — their determination to retain the ground on which PLA forces stood in 1962 and to punish the Indians for trying to take that ground". In general terms, they tried to show the Indians once and for all that China would not acquiesce in a military "reoccupation" policy. Secondary reasons for the attack were to damage Nehru's prestige by exposing Indian weakness and[45] to expose as traitorous Khrushchev's policy of supporting Nehru against a Communist country.[45]

Another factor which might have affected China's decision for war with India was a perceived need to stop a Soviet-U.S.-India encirclement and isolation of China.[37] India's relations with the Soviet Union and United States were both strong at this time, but the Soviets (and Americans) were preoccupied by the Cuban Missile Crisis and would not interfere with the Sino-Indian War. P. B. Sinha suggests that China waited until October to attack because the timing of the war was exactly in parallel with American actions so as to avoid any chance of American or Soviet involvement. Although American buildup of forces around Cuba occurred on the same day as the first major clash at Dhola Post, and China's buildup between 10 and 20 October appeared to coincide exactly with the United States establishment of a blockade against Cuba which began 20 October, the Chinese probably prepared for this before they could anticipate what would happen in Cuba.[42]

In May to June 1962, the KMT government of Republic of China on Taiwan under Chiang Kai-shek's leadership was propagating the policy of 'Reclaim the mainland China', causing fear of invasion from Taiwan among Chinese Communist leadership and the shift of concern to the Southeast. Reluctant to divert resources to the hostitlies in the Himalayas, Chinese leadership thought a two-front war undesirable. From July on, after receiving American assurances that KMT government would not invade, China began to focus on the Indian border.[66]

Garver argues that the Chinese correctly assessed Indian border policies, particularly the Forward Policy, as attempts for incremental seizure of Chinese-controlled territory. On Tibet, Garver argues that one of the major factors leading to China's decision for war with India was a common tendency of humans "to attribute others' behavior to interior motivations, while attributing their own behavior to situational factors". Studies from China published in the 1990s confirmed that the root cause for China going to war with India was the perceived Indian aggression in Tibet, with the forward policy simply catalysing the Chinese reaction.[37]

Neville Maxwell and Allen Whiting argue that the Chinese leadership believed they were defending territory that was legitimately Chinese, and which was already under de facto Chinese occupation prior to Indian advances, and regarded the Forward Policy as an Indian attempt at creeping annexation.[37] Mao Zedong himself compared the Forward Policy to a strategic advance in Chinese chess:

International reactions

According to James Calvin, western nations at the time viewed China as an aggressor during the China–India border war, and saw the war as part of a monolithic communist objective for a world dictatorship of the proletariat. This was further triggered by Mao's statement that: "the way to world conquest lies through Havana, Accra and Calcutta". The United States was unequivocal in its recognition of the Indian boundary claims in the eastern sector, while not supporting the claims of either side in the western sector.[79][80] Britain, on the other hand, agreed with the Indian position completely, with the foreign secretary stating, 'we have taken the view of the government of India on the present frontiers and the disputed territories belong to India.'[80]

The Chinese military action has been viewed by the United States as part of the PRC's policy of making use of aggressive wars to settle its border disputes and to distract both its own population and international opinion from its internal issues.[81] The Kennedy administration was disturbed by what they considered "blatant Chinese communist aggression against India". In a May 1963 National Security Council meeting, contingency planning on the part of the United States in the event of another Chinese attack on India was discussed and nuclear options were considered.[82] After listening to advisers, Kennedy stated "We should defend India, and therefore we will defend India."[82][83] By 1964, China had developed its own nuclear weapon which would have likely caused any American nuclear policy in defense of India to be reviewed.[82]

The non-aligned nations remained mostly uninvolved, and only Egypt (officially the United Arab Republic) openly supported India.[84] Of the non-aligned nations, six, Egypt, Burma, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Ghana and Indonesia, met in Colombo on 10 December 1962.[85] The proposals stipulated a Chinese withdrawal of 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the customary lines without any reciprocal withdrawal on India's behalf.[85] The failure of these six nations to unequivocally condemn China deeply disappointed India.[84]

Pakistan also shared a disputed boundary with China, and had proposed to India that the two countries adopt a common defence against "northern" enemies (i.e. China), which was rejected by India, citing nonalignment.[42] In 1962, Pakistani president Muhammad Ayub Khan made clear to India that Indian troops could safely be transferred from the Pakistan frontier to the Himalayas.[86] But, after the war, Pakistan improved its relations with China.[87] It began border negotiations on 13 October 1962, concluding them in December.[35] In 1963, the China-Pakistan Border Treaty was signed, as well as trade, commercial, and barter treaties.[87] Pakistan conceded its northern claim line in Pakistani-controlled Kashmir to China in favour of a more southerly boundary along the Karakoram Range.[35][85][87] The border treaty largely set the border along the MacCartney-Macdonald Line.[23] India's military failure against China would embolden Pakistan to initiate the Second Kashmir War with India in 1965.

Foreign involvement

During the conflict, Nehru wrote two letters on 19 November 1962 to U.S. President Kennedy, asking for 12 squadrons of fighter jets and a modern radar system. These jets were seen as necessary to beef up Indian air strength so that air-to-air combat could be initiated safely from the Indian perspective. Bombing troops was seen as unwise for fear of Chinese retaliatory action. Nehru also asked that these aircraft be manned by American pilots until Indian airmen were trained to replace them. These requests were rejected by the Kennedy Administration, which was involved in the Cuban Missile Crisis during most of the Sino-Indian War. The U.S. nonetheless provided non-combat assistance to Indian forces and planned to send the carrier USS Kitty Hawk to the Bay of Bengal to support India in case of an air war.[88]

As the Sino-Soviet split had already emerged, Moscow, while remaining formally neutral, made a major effort to render military assistance to India, especially with the sale of advanced MiG warplanes. The U.S. and Britain refused to sell these advanced weapons so India turned to the USSR. India and the USSR reached an agreement in August 1962 (before the Cuban Missile Crisis) for the immediate purchase of twelve MiG-21s as well as for Soviet technical assistance in the manufacture of these aircraft in India. According to P.R. Chari, "The intended Indian production of these relatively sophisticated aircraft could only have incensed Peking so soon after the withdrawal of Soviet technicians from China." In 1964 further Indian requests for American jets were rejected. However, Moscow offered loans, low prices and technical help in upgrading India's armaments industry. India by 1964 was a major purchaser of Soviet arms.[89]

According to Indian diplomat G. Parthasarathy, "only after we got nothing from the US did arms supplies from the Soviet Union to India commence."[90] India's favored relationship with Moscow continued into the 1980s, but ended after the collapse of Soviet Communism in 1991.[91][92] In his memoirs, the then Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, says: "I think Mao created the Sino-Indian conflict precisely in order to draw the Soviet Union into it. He wanted to put us in the position of having to no choice but to support him. He wanted to be the one who decided what we should do. But Mao made a mistake in thinking we would agree to sacrifice our independence in foreign policy."[93]

Aftermath

China

According to China's official military history, the war achieved China's policy objectives of securing borders in its western sector, as China continued its de facto control of the Aksai Chin.

According to James Calvin, even though China won a military victory it lost in terms of its international image. China's first nuclear weapon test in October 1964 and its support of Pakistan in the 1965 India Pakistan War tended to confirm the American view of communist world objectives, including Chinese influence over Pakistan.

Lora Saalman opined in a 2011 study of Chinese military publications, that while the war led to much blame, debates and acted as catalyst for the military modernisation of India, the war is now treated as basic reportage of facts with relatively diminished interest by Chinese analysts.[94]

This changed during the 2017 Doklam crisis, when the Chinese official media served up a daily vitriol of teaching a "bitter lesson" as in 1962.[95]

Diplomatic process

In 1993 and 1996, the two sides signed the Sino-Indian Bilateral Peace and Tranquility Accords, agreements to maintain peace and tranquility along the Line of Actual Control. Ten meetings of a Sino-Indian Joint Working Group (SIJWG) and five of an expert group have taken place to determine where the LoAC lies, but little progress has occurred.

On 20 November 2006,[110] Indian politicians from Arunachal Pradesh expressed their concern over Chinese military modernization and appealed to parliament to take a harder stance on the PRC following a military buildup on the border similar to that in 1962.[111] Additionally, China's military aid to Pakistan as well is a matter of concern to the Indian public,[69] as the two sides have engaged in various wars.

On 6 July 2006, the historic Silk Road passing through this territory via the Nathu La pass was reopened. Both sides have agreed to resolve the issues by peaceful means.

In October 2011,[112] it was stated that India and China will formulate a border mechanism to handle different perceptions as to the Line of Actual Control and resume the bilateral army exercises between the Indian and Chinese army from early 2012.[113][114]