Southern American English

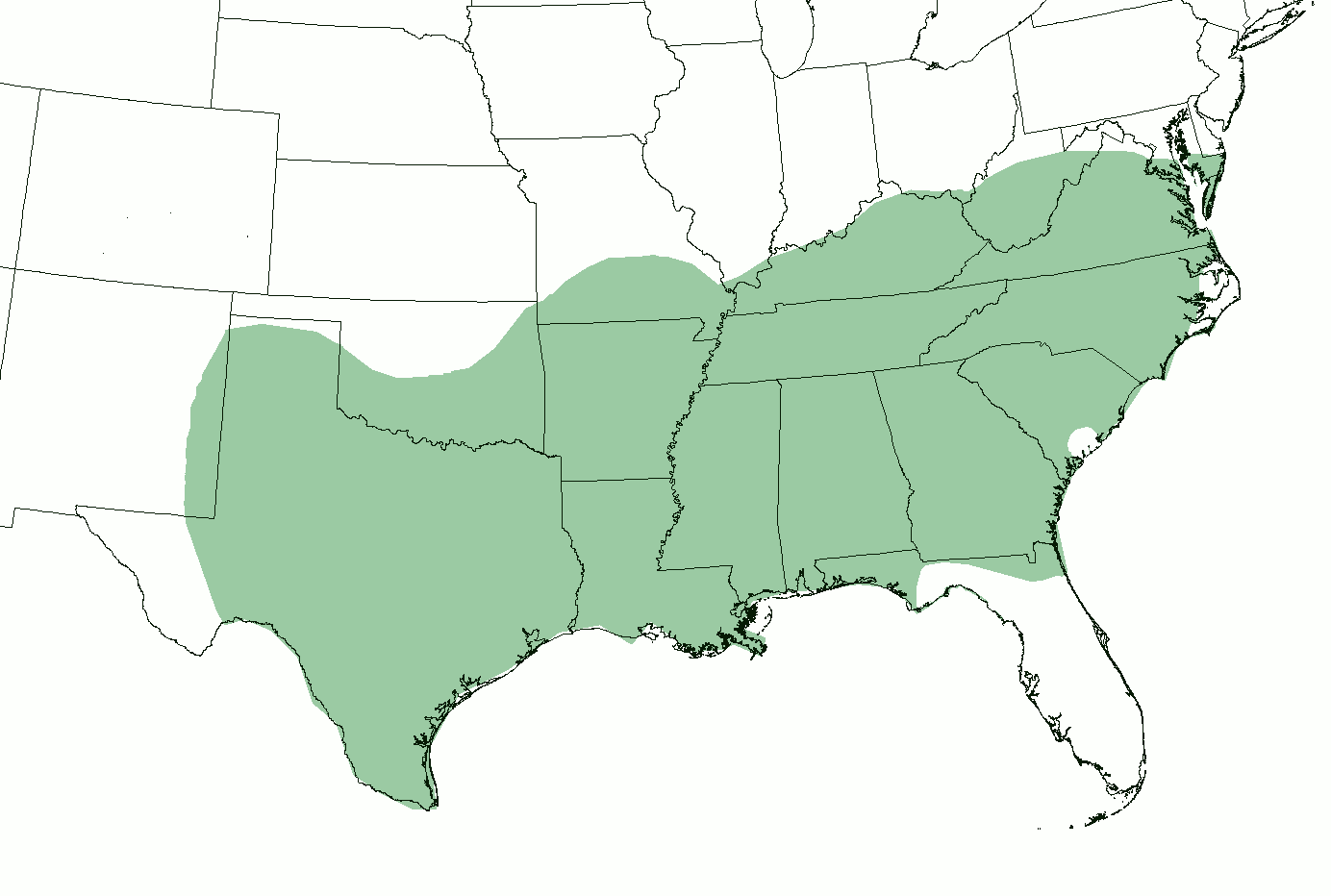

Southern American English or Southern U.S. English is a regional dialect[1][2] or collection of dialects of American English spoken throughout the Southern United States, though concentrated increasingly in more rural areas, and spoken primarily by White Southerners.[3] In terms of accent, its most innovative forms include southern varieties of Appalachian English and certain varieties of Texan English.[4] Popularly known in the United States as a Southern accent or simply Southern,[5][6][7] Southern American English now comprises the largest American regional accent group by number of speakers.[8] Formal, much more recent terms within American linguistics include Southern White Vernacular English and Rural White Southern English.[9][10]

This article is about English as spoken in the Southern United States. For older English dialects spoken in this same region, see Older Southern American English. For English as spoken in South America, see South American English.Southern American English

History[edit]

A diversity of earlier Southern dialects once existed: a consequence of the mix of English speakers from the British Isles (including largely English and Scots-Irish immigrants) who migrated to the American South in the 17th and 18th centuries, with particular 19th-century elements also borrowed from the London upper class and enslaved African-Americans. By the 19th century, this included distinct dialects in eastern Virginia, the greater Lowcountry area surrounding Charleston, the Appalachian upcountry region, the Black Belt plantation region, and secluded Atlantic coastal and island communities.

Following the American Civil War, as the South's economy and migration patterns fundamentally transformed, so did Southern dialect trends.[11] Over the next few decades, Southerners moved increasingly to Appalachian mill towns, to Texan farms, or out of the South entirely.[11] The main result, further intensified by later upheavals such as the Great Depression, the Dust Bowl and perhaps World War II, is that a newer and more unified form of Southern American English consolidated, beginning around the last quarter of the 19th century, radiating outward from Texas and Appalachia through all the traditional Southern States until around World War II.[12][13] This newer Southern dialect largely superseded the older and more diverse local Southern dialects, though it became quickly stigmatized in American popular culture. As a result, since around the 1950s and 1960s, the notable features of this newer Southern accent have been in a gradual decline, particularly among younger and more urban Southerners, though less so among rural white Southerners.

Social perceptions[edit]

In the United States, there is a general negative stigma surrounding the Southern dialect. Non–Southern Americans tend to associate a Southern accent with lower social and economic status, cognitive and verbal slowness, lack of education, ignorance, bigotry, or religious or political conservatism,[21] using common labels like "hick", "hillbilly",[22] or "redneck accent".[23] Meanwhile, Southerners themselves tend to have mixed judgments of their accent, some similarly negative but others positively associating it with a laid-back, plain, or humble attitude.[24] The accent is also associated nationwide with the military, NASCAR, and country music. Furthermore, non–Southern American country singers typically imitate a Southern accent in their music.[23] The sum of negative associations nationwide, however, is the main presumable cause of a gradual decline of Southern accent features, since the middle of the 20th century onwards, particularly among younger and more urban residents of the South.[16]

In a study of children's attitudes about accents published in 2012, Tennessee children from 5 to 6 were indifferent about the qualities of persons with different accents, but children from Chicago were not. Chicago children from 5 to 6 (speakers of Northern American English) were much more likely to attach positive traits to Northern speakers than Southern ones. The study's results suggest that social perceptions of Southern English are taught by parents to children and exist for no biological reason.[25]

In 2014, the US Department of Energy at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee offered a voluntary "Southern accent reduction" class so that employees could be "remembered for what they said rather than their accents". The course offered accent neutralization through codeswitching. The class was canceled because of the resulting controversy and complaints from Southern employees, who were offended by the class since it stigmatized Southern accents.[26]

Before becoming a phonologically unified dialect region, the South was once home to an array of much more diverse accents at the local level. Features of the deeper interior Appalachian South largely became the basis for the newer Southern regional dialect; thus, older Southern American English primarily refers to the English spoken outside of Appalachia: the coastal and former plantation areas of the South, best documented before the Civil War, on the decline during the early 1900s, and non-existent in speakers born since the civil rights movement.[70]

Little unified these older Southern dialects since they never formed a single homogeneous dialect region to begin with. Some older Southern accents were rhotic (most strongly in Appalachia and west of the Mississippi), while the majority were non-rhotic (most strongly in plantation areas); however, wide variation existed. Some older Southern accents showed (or approximated) Stage 1 of the Southern Vowel Shift—namely, the glide weakening of /aɪ/—however, it is virtually unreported before the very late 1800s.[71] In general, the older Southern dialects lacked the Mary–marry–merry, cot–caught, horse–hoarse, wine–whine, full–fool, fill–feel, and do–dew mergers, all of which are now common to, or encroaching on, all varieties of present-day Southern American English. Older Southern sound systems included those local to the:[10]