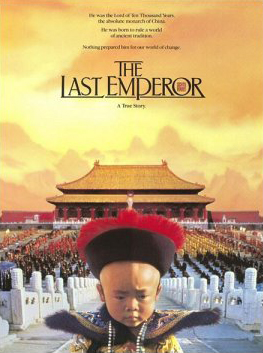

The Last Emperor

The Last Emperor (Italian: L'ultimo imperatore) is a 1987 epic biographical drama film about the life of Puyi, the final Emperor of China. It is directed by Bernardo Bertolucci from a screenplay he co-wrote with Mark Peploe, which was adapted from Puyi's 1964 autobiography, and independently produced by Jeremy Thomas.[5]

For other uses, see Last Emperor (disambiguation).The Last Emperor

- Mark Peploe

- Bernardo Bertolucci

From Emperor to Citizen: The Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Puyi

1960 autobiography

by Puyi

- Ryuichi Sakamoto

- David Byrne

- Cong Su

- 4 October 1987 (Tokyo)

- 23 October 1987 (Italy)

- 26 February 1988 (United Kingdom)

163 minutes[1]

- United Kingdom

- Italy

- France

- China [2]

- English

- Mandarin

- Japanese

$23.8 million[3]

$44 million[4]

The film depicts Puyi's life from his ascent to the throne as a small boy to his imprisonment and political rehabilitation by the Chinese Communist Party. It stars John Lone in the eponymous role, with Peter O'Toole, Joan Chen, Ruocheng Ying, Victor Wong, Dennis Dun, Vivian Wu, Lisa Lu, and Ryuichi Sakamoto (who also composed the film score with David Byrne and Cong Su). It was the first Western feature film authorised by the People's Republic of China to film in the Forbidden City in Beijing.[3]

The Last Emperor premiered at the 1987 Tokyo International Film Festival, and was released in the United States by Columbia Pictures on November 18. It earned widespread positive reviews from critics and was also a commercial success. At the 60th Academy Awards, it won all nine Oscars it was nominated for, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay. It also won several other accolades, including three BAFTA Awards, four Golden Globe Awards, nine David di Donatello Awards, and a Grammy Award for its musical score. The film was converted into 3D and shown in the Cannes Classics section at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival.[6]

Plot[edit]

By 1950, the 44-year old Puyi, former Emperor of China, has been in custody for five years since his capture by the Red Army during the Soviet invasion of Manchuria. In the recently established People's Republic of China, Puyi arrives as a political prisoner and war criminal at the Fushun Prison. Soon after his arrival, Puyi attempts suicide, but is quickly rescued and told he must stand trial.

42 years earlier, in 1908, a toddler Puyi is summoned to the Forbidden City by the dying Empress Dowager Cixi. After telling him that the previous emperor had died earlier that day, Cixi tells Puyi that he is to be the next emperor. After his coronation, Puyi, frightened by his new surroundings, repeatedly expresses his wish to go home, but is denied. Despite having scores of palace eunuchs and maids to wait on him, his only real friend is his wet nurse, Ar Mo.

As he grows up, his upbringing is confined entirely to the imperial palace and he is prohibited from leaving. One day, he is visited by his younger brother, Pujie, who tells him he is no longer Emperor and that China has become a republic; that same day, Ar Mo is forced to leave. In 1919, Reginald Johnston is appointed as Puyi's tutor and gives him a Western-style education, and Puyi becomes increasingly desirous to leave the Forbidden City. Johnston, wary of the courtiers' expensive lifestyle, convinces Puyi that the best way of achieving this is through marriage; Puyi subsequently weds Wanrong, with Wenxiu as a secondary consort.

Puyi then sets about reforming the Forbidden City, including expelling the palace eunuchs. However, in 1924, he himself is expelled from the palace and exiled to Tientsin following the Beijing Coup. He leads a decadent life as a playboy and Anglophile, and sides with Japan after the Mukden Incident. During this time, Wenxiu divorces him, but Wanrong remains and eventually succumbs to opium addiction. In 1934, the Japanese crown him "Emperor" of their puppet state of Manchukuo, though his supposed political supremacy is undermined at every turn. Wanrong gives birth to a child, but the baby is murdered at birth by the Japanese and proclaimed stillborn. He remains the nominal ruler of the region until his capture by the Soviet Red Army.

Under the Communist re-education program for political prisoners, Puyi is coerced by his interrogators to formally renounce his forced collaboration with the Japanese invaders during the Second Sino-Japanese War. After heated discussions with Jin Yuan, the warden of the Fushun Prison, and watching a film detailing the wartime atrocities committed by the Japanese, Puyi eventually recants and is considered rehabilitated by the government; he is subsequently released in 1959.

Several years later in 1967, Puyi has become a simple gardener who lives a peasant proletarian existence following the rise of Mao Zedong's cult of personality and the Cultural Revolution. On his way home from work, he happens upon a Red Guard parade, celebrating the rejection of landlordism by the communists. He sees Jin Yuan, now one of the political prisoners punished as an anti-revolutionary in the parade, forced to wear a dunce cap and a sandwich board bearing punitive slogans.

Puyi later visits the Forbidden City where he meets an assertive young boy wearing the red scarf of the Pioneer Movement. The boy orders Puyi to step away from the throne, but Puyi proves that he was indeed the Son of Heaven before approaching the throne. Behind it, Puyi finds a 60-year-old pet cricket that he was given by palace official Chen Baochen on his coronation day and gives it to the child. Amazed by the gift, the boy turns to talk to Puyi, but finds that he has disappeared.

In 1987, a tour guide leads a group through the palace. Stopping in front of the throne, the guide sums up Puyi's life in a few, brief sentences, before concluding that he died in 1967.

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Bernardo Bertolucci proposed the film to the Chinese government as one of two possible projects – the other was an adaptation of La Condition humaine (Man's Fate) by André Malraux. The Chinese preferred The Last Emperor. Producer Jeremy Thomas managed to raise the $25 million budget for his ambitious independent production single-handedly.[7] At one stage, he scoured the phone book for potential financiers.[8] Bertolucci was given complete freedom by the authorities to shoot in The Forbidden City, which had never before been opened up for use in a Western film. For the first ninety minutes of the film, Bertolucci and Storaro made full use of its visual splendour.[7]

Filming[edit]

19,000 extras were needed over the course of the film. The People's Liberation Army (PLA) was drafted in to accommodate.[9]

In a 2010 interview with Bilge Ebiri for Vulture.com, Bertolucci recounted the shooting of the Cultural Revolution scene:

Alternative versions[edit]

The film's theatrical release ran 163 minutes. Deemed too long to show in a single three-hour block on television but too short to spread out over two nights, an extended version was created which runs 218 minutes. Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and director Bernardo Bertolucci have confirmed that this extended version was indeed created as a television miniseries and does not represent a true "director's cut".[43]

Home video[edit]

The Criterion Collection 2008 version of four DVDs adds commentary by Ian Buruma, composer David Byrne, and the Director's interview with Jeremy Isaacs (ISBN 978-1-60465-014-3). It includes a booklet featuring an essay by David Thomson, interviews with production designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti and actor Ying Ruocheng, a reminiscence by Bertolucci, and an essay and production-diary extracts from Fabien S. Gerard.

The film was for quite some time unavailable on DVD or Blu-Ray in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio, as cinematographer Vittorio Storaro had insisted on a cropped 2:1 version that retroactively conforms the film to his Univisium standard. Copies of the film in its original ratio were then rare and sought after by fans of the film.

The film has since been restored in 4K and in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio, and has been released on Blu-ray and UHD in 2023 in several countries using this 4K restoration. [44]