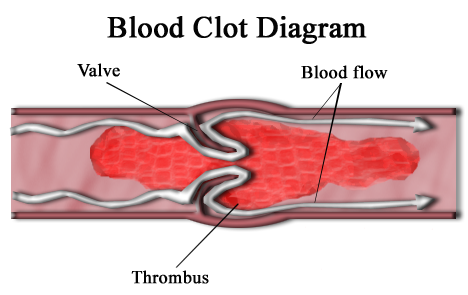

Thrombus

A thrombus (pl.: thrombi), colloquially called a blood clot, is the final product of the blood coagulation step in hemostasis. There are two components to a thrombus: aggregated platelets and red blood cells that form a plug, and a mesh of cross-linked fibrin protein. The substance making up a thrombus is sometimes called cruor. A thrombus is a healthy response to injury intended to stop and prevent further bleeding, but can be harmful in thrombosis, when a clot obstructs blood flow through healthy blood vessels in the circulatory system.

For the sea sponge genus, see Thrombus (sponge).Thrombus

Blood clot

abrupt change in mental status, chest pain, cramp-like feeling, fatigue, passing out (syncope), and swelling in the arm and/or leg

bleeding risks from taking anticoagulants, breathing problems, heart attacks, stroke

c. 3–6 months

Superficial thrombophlebiti and Thrombophlebitis migrans

injury to the artery, sepsis or viral infection, immobility

smoking cessation, regular exercise, improved blood flow, management of comorbidities

Anticoagulants: edoxaban, tinzaparin, unfractionated heparin

apixaban, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban

100,000–300,000 each year

In the microcirculation consisting of the very small and smallest blood vessels the capillaries, tiny thrombi known as microclots can obstruct the flow of blood in the capillaries. This can cause a number of problems particularly affecting the alveoli in the lungs of the respiratory system resulting from reduced oxygen supply. Microclots have been found to be a characteristic feature in severe cases of COVID-19 and in long COVID.[1]

Mural thrombi are thrombi that adhere to the wall of a large blood vessel or heart chamber.[2] They are most commonly found in the aorta, the largest artery in the body, more often in the descending aorta, and less often in the aortic arch or abdominal aorta.[2] They can restrict blood flow but usually do not block it entirely. They appear grey-red along with alternating light and dark lines (known as lines of Zahn) which represent bands of white blood cells and red blood cells (darker) entrapped in layers of fibrin.[3]

Treatment[edit]

Once clots have formed, other drugs can be used to promote thrombolysis or clot breakdown. Streptokinase, an enzyme produced by streptococcal bacteria, is one of the oldest thrombolytic drugs.[14] This drug can be administered intravenously to dissolve blood clots in coronary vessels. However, streptokinase causes systemic fibrinolytic state and can lead to bleeding problems. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is a different enzyme that promotes the degradation of fibrin in clots but not free fibrinogen.[14] This drug is made by transgenic bacteria and converts plasminogen into the clot-dissolving enzyme, plasmin.[15] Recent research indicates that tPA could have toxic effects in the central nervous system. In cases of severe stroke, tPA can cross the blood–brain barrier and enter interstitial fluid, where it then increases excitotoxicity, potentially affecting permeability of the blood–brain barrier,[16] and causing cerebral hemorrhage.[17]

There are also some anticoagulants that come from animals that work by dissolving fibrin. For example, Haementeria ghilianii, an Amazon leech, produces an enzyme called hementin from its salivary glands.[18]