Heidelberg University

Heidelberg University, officially the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg (German: Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg; Latin: Universitas Ruperto Carola Heidelbergensis), is a public research university in Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Founded in 1386 on instruction of Pope Urban VI, Heidelberg is Germany's oldest university and one of the world's oldest surviving universities; it was the third university established in the Holy Roman Empire after Vienna and Prague. Since 1899, it has been a coeducational institution.

This article is about the university in Germany. For the university in Ohio, see Heidelberg University (Ohio).

Heidelberg is one of the most prestigious universities in Germany.[6] It is a German Excellence University, part of the U15, as well as a founding member of the League of European Research Universities and the Coimbra Group. The university consists of twelve faculties and offers degree programmes at undergraduate, graduate and postdoctoral levels in some 100 disciplines.[7] The language of instruction is usually German, while a considerable number of graduate degrees are offered in English as well as some in French.[8][9]

As of 2021, 57 Nobel Prize winners have been affiliated with the city of Heidelberg and 33 with the university itself.[10] Modern scientific psychiatry, psychopharmacology, experimental psychology, psychiatric genetics, Mathematical statistics,[11] environmental physics,[12] and modern sociology[13] were introduced as scientific disciplines by Heidelberg students or faculty. Approximately 1,000 doctorates are completed every year, with more than one third of the doctoral students coming from abroad.[14][15] International students from some 130 countries account for more than 20 percent of the entire student body.[16]

Organization[edit]

Governance[edit]

The Rectorate is the 'executive body' of the university, headed by rector Bernhard Eitel. The rectorate consists of the chancellor, Holger Schroeter, who is the head of the central administration and responsible for the university's budgeting, and three pro-rectors, who are responsible for international relations, teaching and communication, and research and structure respectively.

The Senate is the 'legislative branch' of the university. The rector and the members of the rectorate are senators ex officio, as are also the deans of the faculties, as well as the medical and managing directors of the University Hospital, and the university's equal opportunities officer. Another 20 senators are elected for four-year terms, within the following quotas: eight university professors; four academic staff; four delegates of the student body; and four employees of the university administration.

The University Council is the advisory board to the aforementioned entities and encompasses, among others, the former Israeli Ambassador to Germany Avi Primor, as well as CEOs of German industries.[53]

Faculties[edit]

After a 2003 structural reformation, the university consists of 13 faculties, which in turn comprise several disciplines, departments, and institutes. As a consequence of the Bologna process, most faculties now offer Bachelor's, Master's, and Ph.D. degrees to comply with the new European degree standard. Notable exceptions are the undergraduate programs in law, medicine, dentistry and pharmacy, from which students still graduate with the State Examination, a central examination at Master's level held by the State of Baden-Württemberg.

Academic profile[edit]

School statistics[edit]

The university employs more than 15,000 academic staff; most of them are physicians engaged in the University Hospital.[56] As of 2008, the faculty encompasses 4,196 full-time staff, excluding visiting professors as well as graduate research and teaching assistants. 673 faculty members have been drawn from abroad. Heidelberg University also attracts more than 500 international scholars as visiting professors each academic year. The university enrols a total of 26,741 students, including 5,118 international students. In addition there are 1,467 international exchange students at Heidelberg. 23,636 students pursue taught degrees, 4,114 of whom are international students, and 919 are international exchange students. 3,105 students pursue a doctoral degree, including 1,004 international doctoral students and 15 international exchange students. In 2007, the university awarded 994 PhD degrees.[39]

Alumni and faculty of the university include many founders and pioneers of academic disciplines, and a large number of internationally acclaimed philosophers, poets, jurisprudents, theologians, natural and social scientists. 33 Nobel Laureates, at least 18 Leibniz laureates, and two "Oscar" winners have been associated with Heidelberg University. Nine Nobel laureates received the award during their tenure at Heidelberg.[66]

Besides several federal ministers of Germany and prime ministers of German states, five chancellors of Germany have attended the university, the latest being Helmut Kohl, the "Chancellor of the Reunification". Heads of state or government of Belgium, Bulgaria, Greece, Nicaragua, Serbia, Thailand, a British heir apparent, a secretary general of NATO and a director of the International Peace Bureau have also been educated at Heidelberg; among them Nobel Peace laureates Charles Albert Gobat and Auguste Beernaert. Former university affiliates in the field of religion include Pope Pius II, cardinals, bishops, and with Philipp Melanchthon and Zacharias Ursinus, two key leaders of the Protestant Reformation. Outstanding university affiliates in the legal profession include a president of the International Court of Justice, two presidents of the European Court of Human Rights, a president of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, a vice president of the International Criminal Court, an advocate general at the European Court of Justice, at least 16 justices of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany, a president of the Federal Court of Justice, a president of the Federal Court of Finance, a president of the Federal Labor Court, two attorneys general of Germany, and a British law lord. In business, Heidelberg alumni and faculty notably founded, co-founded or presided over ABB; Astor corporate enterprises; BASF; BDA; Daimler AG; Deutsche Bank; EADS; Krupp AG; Siemens and Thyssen AG.

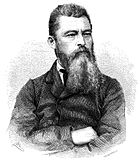

Alumni in the field of arts include classical composer Robert Schumann, philosophers Ludwig Feuerbach and Edmund Montgomery, poet Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff and writers Christian Friedrich Hebbel, Gottfried Keller, Irene Frisch, Heinrich Hoffmann, Sir Muhammad Iqbal, National Hero of the Philippines José Rizal, W. Somerset Maugham, Jean Paul, Literature Nobel laureate Carl Spitteler, and novelist Jagoda Marinić. Amongst Heidelberg alumni in other disciplines are the "Father of Psychology" Wilhelm Wundt, the "Father of Physical Chemistry" J. Willard Gibbs, the "Father of American Anthropology" Franz Boas, Dmitri Mendeleev, who created the periodic table of elements, inventor of the two-wheeler principle Karl Drais, Alfred Wegener, who discovered the continental drift, as well as political theorist Hannah Arendt, gender theorist Judith Butler, political scientist Carl Joachim Friedrich, and sociologists Karl Mannheim, Robert E. Park and Talcott Parsons.

Philosophers Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Karl Jaspers, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Jürgen Habermas served as university professors, as did also the pioneering scientists Hermann von Helmholtz, Robert Wilhelm Bunsen, Gustav Robert Kirchhoff, Emil Kraepelin, the founder of scientific psychiatry, and outstanding social scientists such as Max Weber, the founding father of modern sociology.

Present faculty include Medicine Nobel Laureates Bert Sakmann (1991) and Harald zur Hausen (2008), Chemistry Nobel Laureate Stefan Hell (2014), seven Leibniz laureates, former justice of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany Paul Kirchhof, and Rüdiger Wolfrum, the former president of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea.

In fiction and popular culture[edit]

Literature[edit]

In 1880 Mark Twain humorously detailed his impressions of Heidelberg's student life in A Tramp Abroad. He painted a picture of the university as a school for aristocrats, where students pursued a dandy's lifestyle, and described the great influence the student corporations exerted on the whole of Heidelberg's student life.[108]

In William Somerset Maugham's 1915 masterpiece novel Of Human Bondage, he described the one-year stay of the protagonist Philip Carey at Heidelberg University, in a largely autobiographical way. Heidelberg also featured in the respective film versions of the novel, released in 1934 (starring Leslie Howard as Philip, and Bette Davis as Mildred), 1946 (with Paul Henreid and Eleanor Parker in the lead roles), and 1964 (with Laurence Harvey and Kim Novak in the lead roles).[109]

E. C. Gordon, the hero of Robert Heinlein's 1964 novel Glory Road, mentions his desire for a degree from Heidelberg and the dueling scars to go with it.

In Bernhard Schlink's semi-autobiographical 1995 novel The Reader, Heidelberg University is one of the main scenes of Part II. Nearly a decade after his affair with an older woman came to a mysterious end, Michael Berg, a law student at the university, re-encounters his former lover as she defends herself in a war-crimes trial, which he observes as part of a seminar. The university is also featured in the Academy Award-winning 2008 film version The Reader, starring Kate Winslet, David Kross and Ralph Fiennes.[110][111]

Film and television[edit]

The 1927 silent film The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg, based on Wilhelm Meyer-Förster's play Alt Heidelberg (1903), starring Ramón Novarro and Norma Shearer, continued Mark Twain's image of Heidelberg, showing the story of a German prince who comes to Heidelberg to study there, but falls in love with his innkeeper's daughter. Having been very popular in the first half of the 20th century, it presents the typical student life of the 19th and early 20th century, and it is today considered a masterpiece of the late silent film era.[112] MGM's 1954 color remake The Student Prince, featuring the voice of Mario Lanza, is based on Sigmund Romberg's operetta version of the story.[113] In 2000, a film named Anatomy (film) with Franka Potente was set at Heidelberg and involved a secret society called the Anti-Hyppocratic Society.