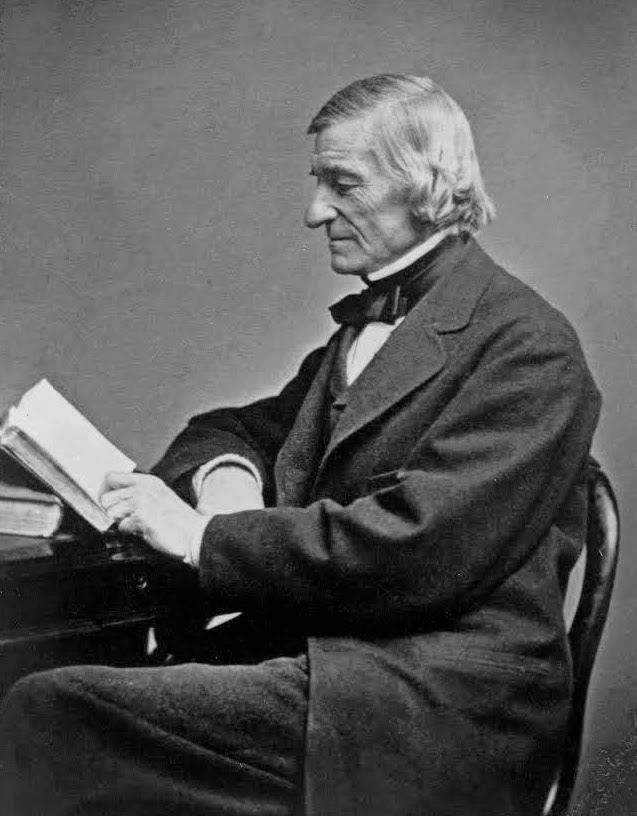

William Barton Rogers

William Barton Rogers (December 7, 1804 – May 30, 1882) was an American geologist, physicist, and educator at the College of William & Mary from 1828 to 1835 and at the University of Virginia from 1835 to 1853. In 1861, Rogers founded the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[1] The university opened in 1865 after the American Civil War. Because of his affiliation with Virginia, Mount Rogers, the highest peak in the state, is named after him.

For other people with the same name, see William Rogers (disambiguation).

William Barton Rogers

office established

John Daniel Runkle

December 7, 1804

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

May 30, 1882 (aged 77)

Boston, Massachusetts, USA

College of William and Mary (no degree)

Founder of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Rogers was born on December 7, 1804, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was the second son of Patrick Kerr Rogers and Hannah Blythe and was of Irish, Scottish, and English extraction. Patrick Rogers was born in Newtownstewart,[2] County Tyrone, Ireland and had immigrated at the end of the 18th century to America, where he graduated from the University of Pennsylvania and practiced medicine. When William Barton was born, Patrick Rogers was tutor at Penn.[3] In 1819 Patrick Rogers became professor of natural philosophy and mathematics at the College of William and Mary, where he remained until his death.[4]

William Barton Rogers had three brothers: James Blythe Rogers (1802–1852), Henry Darwin Rogers (1808–1866), and Robert Empie Rogers (1813–1884). The Rogers brothers would each grow up to be distinguished scientists.[5]

Education and scientific career[edit]

William Barton Rogers was educated by his father Patrick Kerr Rogers and attended the public schools of Baltimore, Maryland.[6] In 1819, his father was appointed as professor of natural history and chemistry at the College of William and Mary in Virginia and the family moved to Williamsburg, Virginia.[7] According to MIT Libraries, William Barton Rogers attended the College of William and Mary from 1819 to 1824, but he "apparently did not receive a degree" and there was no evidence showing that he graduated.[7][8]

William Barton Rogers delivered a series of lectures on science before the Maryland Institute in 1827, and succeeded his father as professor of natural philosophy and chemistry at William and Mary in 1828, where he remained until 1835. During this time, he carried on investigations on dew and on the voltaic battery, and prepared a series of papers on the greensand and calcareous marl minerals of eastern Virginia and their value as fertilizers.[4]

In 1833, his brother Henry had returned from England filled with enthusiasm for geology, and this had prompted Rogers to begin studies in the field. The practical value of his article on greensand caught the eye of the Virginia legislature. Rogers took this opportunity to lobby for a geological survey of Virginia, and he was called upon to organize it in 1835.[9] That same year, he and his brother Henry were elected members of the American Philosophical Society.[10]

By 1835, his brother Henry was state geologist of Pennsylvania, and together the brothers unfolded the historical geology of the Appalachian chain. Among their joint special investigations were the study of the solvent action of water on various minerals and rocks, and the demonstration that "coal beds stand in close genetic relation to the amount of disturbance to which the inclosing strata have been submitted, the coal becoming harder and containing less volatile matter as the evidence of the disturbance increases". In modern terms, this was the realization that the geological process of metamorphism had gradually transformed softer grades of coal, such as lignite, into harder grades, such as anthracite.

Together, the brothers published a paper on "The Laws of Structure of the more Disturbed Zones of the Earth's Crust", in which the wave theory of mountain chains was first announced. This was followed later by William Rogers' statement of the law of distribution of geological faults. These pioneering works contributed to a better understanding of the vast coal beds underlying some parts of the Appalachian region, and helped pave the way for the Industrial Revolution in the United States.

In 1842 the work of the survey closed.[4] State revenues had shrunk beginning in 1837, and the funding for the survey had been cut back. Meanwhile, Rogers had published six "Reports of the Geological Survey of the State of Virginia" (Richmond, 1836–40), though there were few copies, and recognition of their significance was slow to develop. They were later compiled by Jed Hotchkiss and issued in one volume with a map as Papers on the Geology of Virginia (New York, 1884).[9]

In 1835 Rogers also began serving as professor of "natural philosophy" at the University of Virginia (UVa). There he added mineralogy and geology to the curriculum, and did original research in geology, chemistry and physics.[11] While he was chair of the department of philosophy at UVA, he vigorously defended to the Virginia State Legislature the university's refusal to award honorary degrees, a policy which continues today. (Later, MIT would adopt a similar policy from its beginning, and continuing to the present).[12] During the time Rogers lived in Virginia, he was a slaveowner, with two slaves in his household in 1840 and six slaves in 1850;[13] one, his cook, was Isabella Gibbons. In 1849, he married Emma Savage of Boston.[6]

In 1853 he resigned from the University of Virginia, moving to Boston for two principal reasons. First, he wanted to increase his participation in scientific circles under the auspices of the Boston Society of Natural History and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, in whose proceedings and in the American Journal of Science his papers had been published while at UVa. Second, and more importantly, Rogers wanted to implement his innovative scheme for technical education (which could not be achieved within the structure and institutional focuses of UVa), in which he desired to have associated, on one side, scientific research and investigation on the largest scale and, on the other side, agencies for the popular diffusion of useful knowledge. This project continued to occupy his attention until it culminated in the chartering of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1861), of which he became first president.[4]

To raise funds and public awareness of his new Institute, Rogers delivered a course of lectures before the Lowell Institute on "The Application of Science to the Arts" in 1862.

In 1861, he was appointed inspector of gas and gas meters for the state of Massachusetts,[4] a post he accepted reluctantly. During his service, he improved the standards of measurement.[6]

Besides numerous papers on geology, chemistry, and physics, contributed to the proceedings of societies and technical journals, he was the author of:[4]