Industrial Revolution

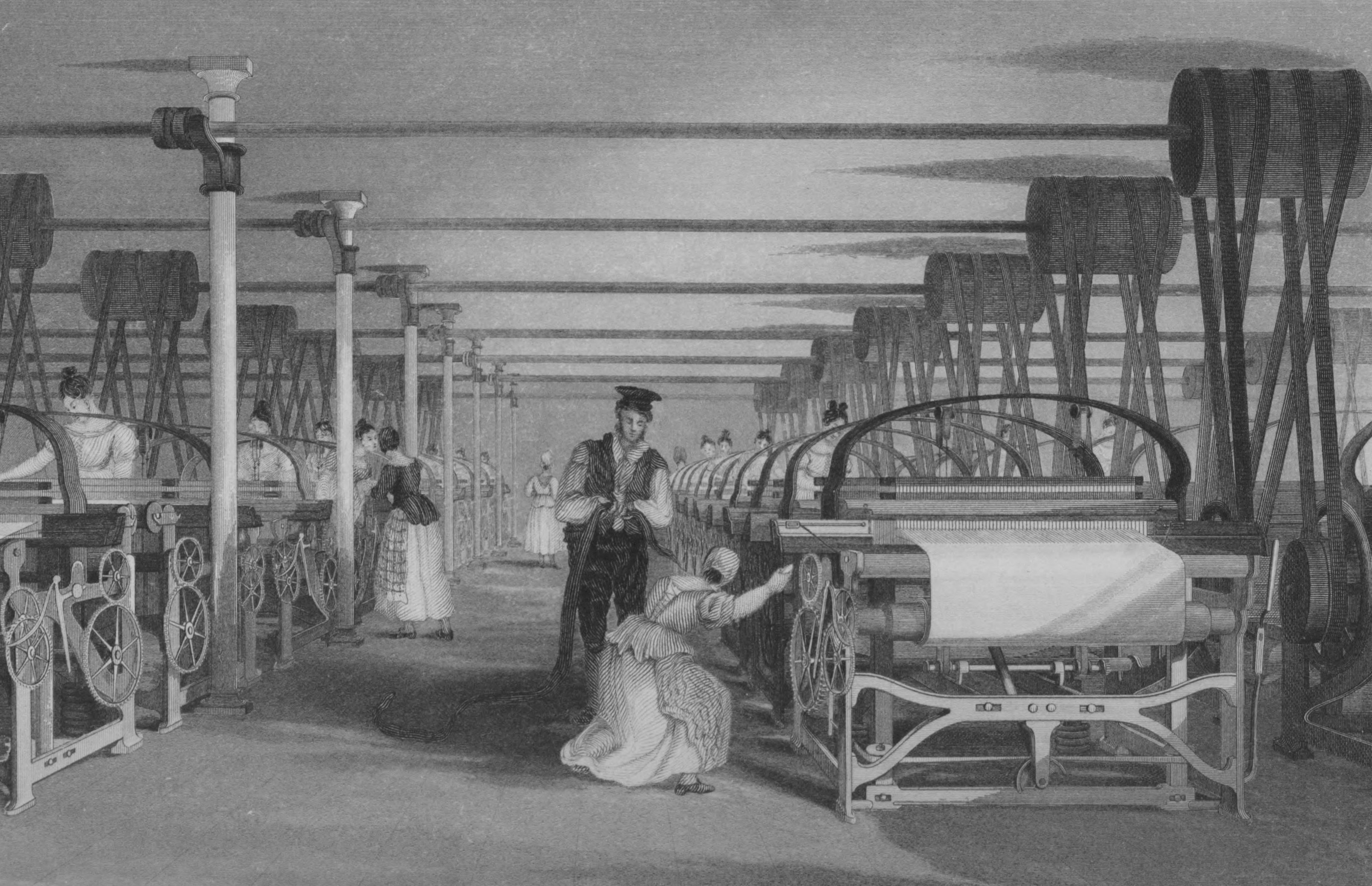

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a period of global transition of the human economy towards more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes that succeeded the Agricultural Revolution. Beginning in Great Britain, the Industrial Revolution spread to continental Europe and the United States, during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840.[1] This transition included going from hand production methods to machines; new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes; the increasing use of water power and steam power; the development of machine tools; and the rise of the mechanized factory system. Output greatly increased, and the result was an unprecedented rise in population and the rate of population growth. The textile industry was the first to use modern production methods,[2]: 40 and textiles became the dominant industry in terms of employment, value of output, and capital invested.

For a more general overview, see Industrialisation.Industrial Revolution

- Mechanized textile production

- Canal construction

- Steam engine

- Factory system

- Iron production increase

Many of the technological and architectural innovations were of British origin.[3][4] By the mid-18th century, Britain was the world's leading commercial nation,[5] controlling a global trading empire with colonies in North America and the Caribbean. Britain had major military and political hegemony on the Indian subcontinent; particularly with the proto-industrialised Mughal Bengal, through the activities of the East India Company.[6][7][8][9] The development of trade and the rise of business were among the major causes of the Industrial Revolution.[2]: 15 Developments in law also facilitated the revolution, such as courts ruling in favour of property rights. An entrepreneurial spirit and consumer revolution helped drive industrialisation in Britain, which after 1800, was emulated in Belgium, the United States, and France.[10]

The Industrial Revolution marked a major turning point in history, comparable only to humanity's adoption of agriculture with respect to material advancement.[11] The Industrial Revolution influenced in some way almost every aspect of daily life. In particular, average income and population began to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth. Some economists have said the most important effect of the Industrial Revolution was that the standard of living for the general population in the Western world began to increase consistently for the first time in history, although others have said that it did not begin to improve meaningfully until the late 19th and 20th centuries.[12][13][14] GDP per capita was broadly stable before the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the modern capitalist economy,[15] while the Industrial Revolution began an era of per-capita economic growth in capitalist economies.[16] Economic historians agree that the onset of the Industrial Revolution is the most important event in human history since the domestication of animals and plants.[17]

The precise start and end of the Industrial Revolution is still debated among historians, as is the pace of economic and social changes.[18][19][20][21] According to Cambridge historian Leigh Shaw-Taylor, Britain was already industrialising in the 17th century, and "Our database shows that a groundswell of enterprise and productivity transformed the economy in the 17th century, laying the foundations for the world’s first industrial economy. Britain was already a nation of makers by the year 1700" and "the history of Britain needs to be rewritten".[22][23] Eric Hobsbawm held that the Industrial Revolution began in Britain in the 1780s and was not fully felt until the 1830s or 1840s,[18] while T. S. Ashton held that it occurred roughly between 1760 and 1830.[19] Rapid adoption of mechanized textiles spinning occurred in Britain in the 1780s,[24] and high rates of growth in steam power and iron production occurred after 1800. Mechanized textile production spread from Great Britain to continental Europe and the United States in the early 19th century, with important centres of textiles, iron and coal emerging in Belgium and the United States and later textiles in France.[2]

An economic recession occurred from the late 1830s to the early 1840s when the adoption of the Industrial Revolution's early innovations, such as mechanized spinning and weaving, slowed as their markets matured; and despite the increasing adoption of locomotives, steamboats and steamships, and hot blast iron smelting. New technologies such as the electrical telegraph, widely introduced in the 1840s and 1850s in the United Kingdom and the United States, were not powerful enough to drive high rates of economic growth.

Rapid economic growth began to reoccur after 1870, springing from a new group of innovations in what has been called the Second Industrial Revolution. These included new steel-making processes, mass production, assembly lines, electrical grid systems, the large-scale manufacture of machine tools, and the use of increasingly advanced machinery in steam-powered factories.[2][25][26][27]

Etymology

The earliest recorded use of the term "Industrial Revolution" was in July 1799 by French envoy Louis-Guillaume Otto, announcing that France had entered the race to industrialise.[28] In his 1976 book Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society, Raymond Williams states in the entry for "Industry": "The idea of a new social order based on major industrial change was clear in Southey and Owen, between 1811 and 1818, and was implicit as early as Blake in the early 1790s and Wordsworth at the turn of the [19th] century." The term Industrial Revolution applied to technological change was becoming more common by the late 1830s, as in Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui's description in 1837 of la révolution industrielle.[29]

Friedrich Engels in The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 spoke of "an industrial revolution, a revolution which at the same time changed the whole of civil society". Although Engels wrote his book in the 1840s, it was not translated into English until the late 19th century, and his expression did not enter everyday language until then. Credit for popularising the term may be given to Arnold Toynbee, whose 1881 lectures gave a detailed account of the term.[30]

Economic historians and authors such as Mendels, Pomeranz, and Kridte argue that proto-industrialization in parts of Europe, the Muslim world, Mughal India, and China created the social and economic conditions that led to the Industrial Revolution, thus causing the Great Divergence.[31][32][33] Some historians, such as John Clapham and Nicholas Crafts, have argued that the economic and social changes occurred gradually and that the term revolution is a misnomer. This is still a subject of debate among some historians.[34]

Requirements

Six factors facilitated industrialization: high levels of agricultural productivity, such as that reflected in the British Agricultural Revolution, to provide excess manpower and food; a pool of managerial and entrepreneurial skills; available ports, rivers, canals, and roads to cheaply move raw materials and outputs; natural resources such as coal, iron, and waterfalls; political stability and a legal system that supported business; and financial capital available to invest. Once industrialization began in Great Britain, new factors can be added: the eagerness of British entrepreneurs to export industrial expertise and the willingness to import the process. Britain met the criteria and industrialized starting in the 18th century, and then it exported the process to western Europe (especially Belgium, France, and the German states) in the early 19th century. The United States copied the British model in the early 19th century, and Japan copied the Western European models in the late 19th century.[35][36]

Industrialisation beyond Great Britain

Europe

The Industrial Revolution in continental Europe came later than in Great Britain. It started in Belgium and France, then spread to the German states by the middle of the 19th century. In many industries, this involved the application of technology developed in Britain in new places. Typically, the technology was purchased from Britain or British engineers and entrepreneurs moved abroad in search of new opportunities. By 1809, part of the Ruhr Valley in Westphalia was called 'Miniature England' because of its similarities to the industrial areas of Britain. Most European governments provided state funding to the new industries. In some cases (such as iron), the different availability of resources locally meant that only some aspects of the British technology were adopted.[186][187]

New Industrialism

The New Industrialist movement advocates for increasing domestic manufacturing while reducing emphasis on a financial-based economy that relies on real estate and trading speculative assets. New Industrialism has been described as "supply-side progressivism" or embracing the idea of "Building More Stuff".[219] New Industrialism developed after the China Shock that resulted in lost manufacturing jobs in the U.S. after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. The movement strengthened after the reduction of manufacturing jobs during the Great Recession and when the U.S. was not able to manufacture enough tests or facemasks during the COVID-19 pandemic.[220] New Industrialism calls for building enough housing to satisfy demand in order to reduce the profit in land speculation, to invest in infrastructure, and to develop advanced technology to manufacture green energy for the world.[220] New Industrialists believe that the United States is not building enough productive capital and should invest more into economic growth.[221]