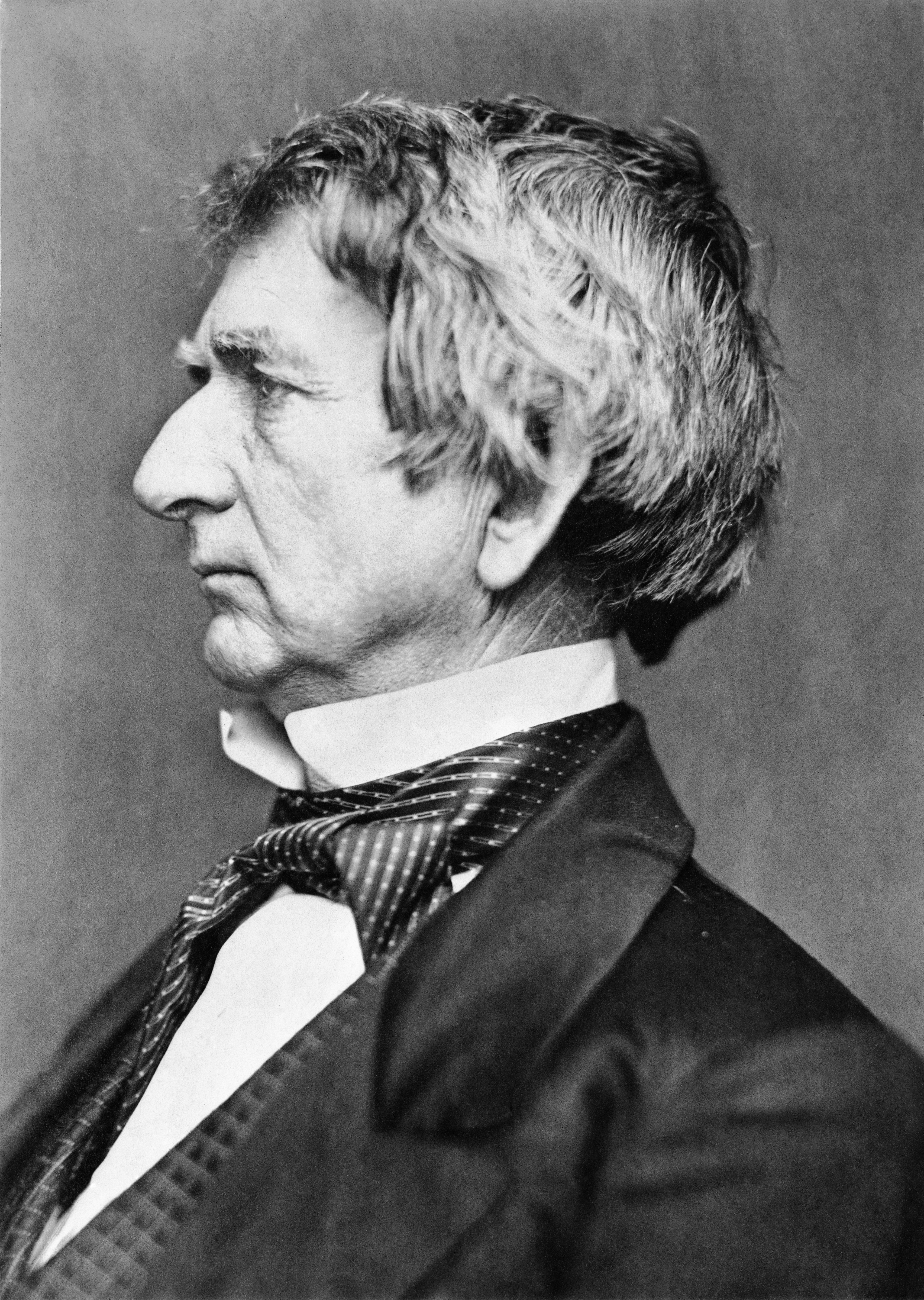

William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (/ˈsuːərd/;[1] May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States senator. A determined opponent of the spread of slavery in the years leading up to the American Civil War, he was a prominent figure in the Republican Party in its formative years, and was praised for his work on behalf of the Union as Secretary of State during the Civil War. He also negotiated the treaty for the United States to purchase the Alaska Territory.

For other people named William Seward, see William Seward (disambiguation).

William H. Seward

October 10, 1872 (aged 71)

Auburn, New York, U.S.

- Anti-Masonic (before 1834)

- Whig (1834–1855)

- Republican (after 1855)

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__subtitleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__call_to_action.textDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

Seward was born in 1801 in the village of Florida, in Orange County, New York, where his father was a farmer and owned slaves. He was educated as a lawyer and moved to the Central New York town of Auburn. Seward was elected to the New York State Senate in 1830 as an Anti-Mason. Four years later, he became the gubernatorial nominee of the Whig Party. Though he was not successful in that race, Seward was elected governor in 1838 and won a second two-year term in 1840. During this period, he signed several laws that advanced the rights of and opportunities for black residents, as well as guaranteeing jury trials for fugitive slaves in the state. The legislation protected abolitionists, and he used his position to intervene in cases of freed black people who were enslaved in the South.

After many years of practicing law in Auburn, he was elected by the state legislature to the U.S. Senate in 1849. Seward's strong stances and provocative words against slavery brought him hatred in the South. He was re-elected to the Senate in 1855, and soon joined the nascent Republican Party, becoming one of its leading figures. As the 1860 presidential election approached, he was regarded as the leading candidate for the Republican nomination. Several factors, including attitudes to his vocal opposition to slavery, his support for immigrants and Catholics, and his association with editor and political boss Thurlow Weed, worked against him, and Abraham Lincoln secured the presidential nomination. Although devastated by his loss, he campaigned for Lincoln, who appointed him Secretary of State after winning the election.

Seward did his best to stop the southern states from seceding; once that failed, he devoted himself wholeheartedly to the Union cause. His firm stance against foreign intervention in the Civil War helped deter the United Kingdom and France from recognizing the independence of the Confederate States. He was one of the targets of the 1865 assassination plot that killed Lincoln and was seriously wounded by conspirator Lewis Powell. Seward remained in his post through the presidency of Andrew Johnson, during which he negotiated the Alaska Purchase in 1867 and supported Johnson during his impeachment. His contemporary Carl Schurz described Seward as "one of those spirits who sometimes will go ahead of public opinion instead of tamely following its footprints".[2]

Early life[edit]

Seward was born on May 16, 1801, in the small community of Florida, New York, in Orange County.[3] He was the fourth son of Samuel Sweezy Seward and his wife Mary (Jennings) Seward.[4] Samuel Seward was a wealthy landowner and slaveholder in New York State; slavery was not fully abolished in the state until 1827.[5] Florida, located some 60 miles (100 km) north of New York City and west of the Hudson River, was a small rural village of perhaps a dozen homes. Young Seward attended school there, and also in the nearby county seat of Goshen.[6] He was a bright student who enjoyed his studies. In later years, one of the former family slaves would relate that instead of running away from school to go home, Seward would run away from home to go to school.[7]

At the age of 15, Henry—he was known by his middle name as a boy—was sent to Union College in Schenectady, New York. Admitted to the sophomore class, Seward was an outstanding student and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. Seward's fellow students included Richard M. Blatchford, who became a lifelong legal and political associate.[8] Samuel Seward kept his son short on cash, and in December 1818—during the middle of Henry's final year at Union—the two quarreled about money. The younger Seward returned to Schenectady but soon left school in company with a fellow student, Alvah Wilson. The two took a ship from New York to Georgia, where Wilson had been offered a job as rector, or principal, of a new academy in rural Putnam County. En route, Wilson took a job at another school, leaving Seward to continue on to Eatonton in Putnam County. The trustees interviewed the 17-year-old Seward and found his qualifications acceptable.[9]

Seward enjoyed his time in Georgia, where he was accepted as an adult for the first time. He was treated hospitably but also witnessed the ill-treatment of slaves.[10] Seward was persuaded to return to New York by his family and did so in June 1819. As it was too late for him to graduate with his class, he studied law at an attorney's office in Goshen before returning to Union College, securing his degree with highest honors in June 1820.[10]

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#2__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#2__descriptionDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

U.S. Senator[edit]

First term[edit]

William Seward was sworn in as senator from New York on March 5, 1849, during the brief special session called to confirm President Taylor's Cabinet nominees. Seward was seen as having influence over Taylor. Taking advantage of an acquaintance with Taylor's brother, Seward met with the former general several times before Inauguration Day (March 4) and was friendly with Cabinet officers. Taylor hoped to gain the admission of California to the Union, and Seward worked to advance his agenda in the Senate.[58]

The regular session of Congress that began in December 1849 was dominated by the issue of slavery. Senator Clay advanced a series of resolutions, which became known as the Compromise of 1850, giving victories to both North and South. Seward opposed the pro-slavery elements of the Compromise, and in a speech on the Senate floor on March 11, 1850, invoked a "higher law than the Constitution". The speech was widely reprinted and made Seward the leading anti-slavery advocate in the Senate.[59] President Taylor took a stance sympathetic to the North, but his death in July 1850 caused the accession of the pro-Compromise Fillmore and ended Seward's influence over patronage. The Compromise passed, and many Seward adherents in federal office in New York were replaced by Fillmore appointees.[60]

1868 election, retirement and death[edit]

Seward hoped that Johnson would be nominated at the 1868 Democratic National Convention, but the delegates chose former New York governor Horatio Seymour. The Republicans chose General Ulysses S. Grant, who had a hostile relationship with Johnson. Seward gave a major speech on the eve of the election, endorsing Grant, who was easily elected. Seward met twice with Grant after the election, leading to speculation that he was seeking to remain as secretary for a third presidential term. However, the president-elect had no interest in retaining Seward, and the secretary resigned himself to retirement. Grant refused to have anything to do with Johnson, even declining to ride to his inauguration in the same carriage as the outgoing president, as was customary. Despite Seward's attempts to persuade him to attend Grant's swearing-in, Johnson and his Cabinet spent the morning of March 4, 1869, at the White House dealing with last-minute business, then left once the time for Grant to be sworn in had passed. Seward returned to Auburn.[185]

Restless in Auburn, Seward embarked on a trip across North America by the new transcontinental railroad. In Salt Lake City, Utah Territory, he met with Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who had worked as a carpenter on Seward's house (then belonging to Judge Miller) as a young man. On reaching the Pacific Coast, the Seward party sailed north on the steamer Active[186] to visit Sitka, Department of Alaska, part of the vast wilderness Seward had acquired for the U.S. After spending time in Oregon and California, the party went to Mexico, where he was given a hero's welcome. After a visit to Cuba, he returned to the U.S.,[187] concluding his nine-month trip in March 1870.[188]

In August 1870, Seward embarked on another trip, this time westbound around the world. With him was Olive Risley, daughter of a Treasury Department official, to whom he became close in his final year in Washington. They visited Japan, then China, where they walked on the Great Wall. During the trip, they decided that Seward would adopt Olive, and he did so, thus putting an end to gossip and the fears of his sons that Seward would remarry late in life. They spent three months in India, then journeyed through the Middle East and Europe, not returning to Auburn until October 1871.[189]

Back in Auburn, Seward began his memoirs, but only reached his thirties before putting it aside to write of his travels.[d] In these months he was steadily growing weaker. On October 10, 1872, he worked at his desk in the morning as usual, then complained of trouble breathing. Seward grew worse during the day, as his family gathered around him. Asked if he had any final words, he said, "Love one another".[190] Seward died that afternoon. His funeral a few days later was preceded by the people of Auburn and nearby filing past his open casket for four hours. Thurlow Weed was there for the burial of his friend, and Harriet Tubman, a former slave whom the Sewards had aided, sent flowers. President Grant sent his regrets he could not be there.[191][192] William Seward rests with his wife Frances and daughter Fanny (1844–1866), in Fort Hill Cemetery in Auburn.[191][192]

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#4__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#4__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#3__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#3__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$