Alaska Purchase

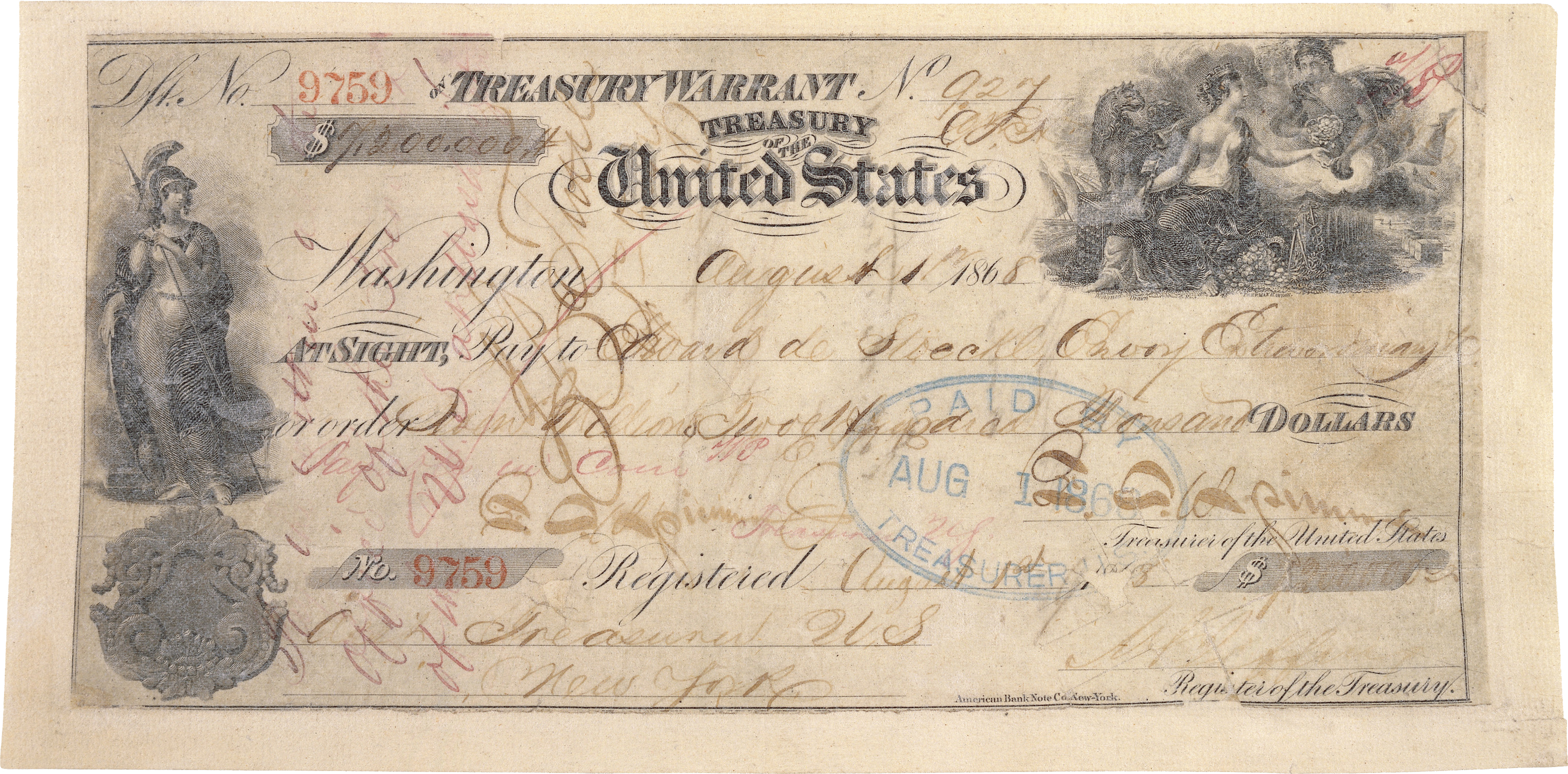

The Alaska Purchase saw the Russian Empire transfer Alaska to the United States for a sum of $7.2 million in 1867 (equivalent to $129 million in 2023). On May 15 of that year, the United States Senate ratified a bilateral treaty that had been signed on March 30, and American sovereignty became legally effective across the territory on October 18.

Signed

During the first half of the 18th century, Russia had established a colonial presence in parts of North America, but few Russians ever settled in Alaska. Alexander II of Russia, having faced a catastrophic defeat in the Crimean War, began exploring the possibility of selling the state's Alaskan possessions, which, in any future war, would be difficult to defend from the United Kingdom. To this end, William H. Seward, the U.S. Secretary of State at the time, entered into negotiations with Russian diplomat Eduard de Stoeckl towards the United States' acquisition of Alaska after the American Civil War. Seward and Stoeckl agreed to a treaty for the sale on March 30, 1867.

At a cost of $0.36 per acre, the United States had grown by 586,412 sq mi (1,518,800 km2).[1] Reactions to the Alaska Purchase among Americans were mostly positive, as many believed that Alaska would serve as a base to expand American trade in Asia. Some opponents labeled the purchase as "Seward's Folly" or "Seward's Icebox"[2] as they contended that the United States had acquired useless land. Nearly all Russian settlers left Alaska in the aftermath of the purchase; Alaska would remain sparsely populated until the Klondike Gold Rush began in 1896. Originally organized as the Department of Alaska, the area was renamed the District of Alaska in 1884 and the Territory of Alaska in 1912, ultimately becoming the modern-day State of Alaska in 1959.

Aftermath[edit]

After the transfer, a number of Russian citizens remained in Sitka, but nearly all of them very soon decided to return to Russia, which was still possible at the expense of the Russian-American Company. Ahllund's story "corroborates other accounts of the transfer ceremony, and the dismay felt by many of the Russians and creoles, jobless and in want, at the rowdy troops and gun-toting civilians who looked on Sitka as merely one more western frontier settlement." Ahllund gives a vivid account of what life was like for civilians in Sitka under US rule and helps to explain why hardly any Russian subject wanted to stay there. Moreover, Ahllund's article is the only known description of the return voyage on the Winged Arrow, a ship that was specially purchased to transport the Russians back to their native country. "The over-crowded vessel, with crewmen who got roaring drunk at every port, must have made the voyage a memorable one." Ahllund mentions stops at the Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands, Tahiti, Brazil, London, and finally Kronstadt, the port for St. Petersburg, where they arrived on August 28, 1869.[30]

American settlers who shared Sumner's belief in the riches of Alaska rushed to the territory but found that much capital was required to exploit its resources, many of which could also be found closer to markets in the contiguous United States. Most soon left, and by 1873, Sitka's population had declined from about 2,500 to a few hundred.[16] The United States acquired an area over twice as large as Texas, but it was not until the great Klondike Gold Rush in 1896 that Alaska generally came to be seen as a valuable addition to U.S. territory.

The seal fishery was one of the chief considerations that induced the United States to purchase Alaska. It provided considerable revenue by the lease of the privilege of taking seals, an amount that was eventually more than the price paid for Alaska. From 1870 to 1890, the seal fisheries yielded 100,000 skins a year. The company to which the administration of the fisheries was entrusted by a lease from the US government paid a rental of $50,000 per annum and in addition thereto $2.62+1⁄2 per skin for the total number taken. The skins were transported to London to be dressed and prepared for world markets. The business grew so large that the earnings of English laborers after the acquisition of Alaska by the United States amounted by 1890 to $12,000,000.[31]

However, exclusive US control of this resource was eventually challenged, and the Bering Sea Controversy resulted when the United States seized over 150 sealing ships flying the British flag, based out of the coast of British Columbia. The conflict between the United States and Britain was resolved by an arbitration tribunal in 1893. The waters of the Bering Sea were deemed to be international waters, contrary to the US contention that they were an internal sea. The US was required to make a payment to Britain, and both nations were required to follow regulations developed to preserve the resource.[31]

Financial return[edit]

The purchase of Alaska has been referenced as a "bargain basement deal"[32] and as the principal positive accomplishment of the otherwise much-maligned presidency of Andrew Johnson.[33][34]

Economist David R. Barker has argued that the US federal government has not earned a positive financial return on the purchase of Alaska. According to Barker, tax revenue and mineral and energy royalties to the federal government have been less than federal costs of governing Alaska plus interest on the borrowed funds used for the purchase.[35]

John M. Miller has taken the argument further by contending that US oil companies that developed Alaskan petroleum resources did not earn enough profits to compensate for the risks that they incurred.[36]

Other economists and scholars, including Scott Goldsmith and Terrence Cole, have criticized the metrics used to reach those conclusions by noting that most contiguous Western states would fail to meet the bar of "positive financial return" using the same criteria and by contending that looking at the increase in net national income, instead of only US Treasury revenue, would paint a much more accurate picture of the financial return of Alaska as an investment.[37]

Alaska Day[edit]

Alaska Day celebrates the formal transfer of Alaska from Russia to the United States, which took place on October 18, 1867, according to the Gregorian calendar which came into effect in Alaska the day following the transfer, replacing the Julian calendar, which was used by the Russians (the Julian calendar in the 19th century was 12 days behind the Gregorian calendar). Alaska Day is a holiday for all state workers.[38]