Biblical apocrypha

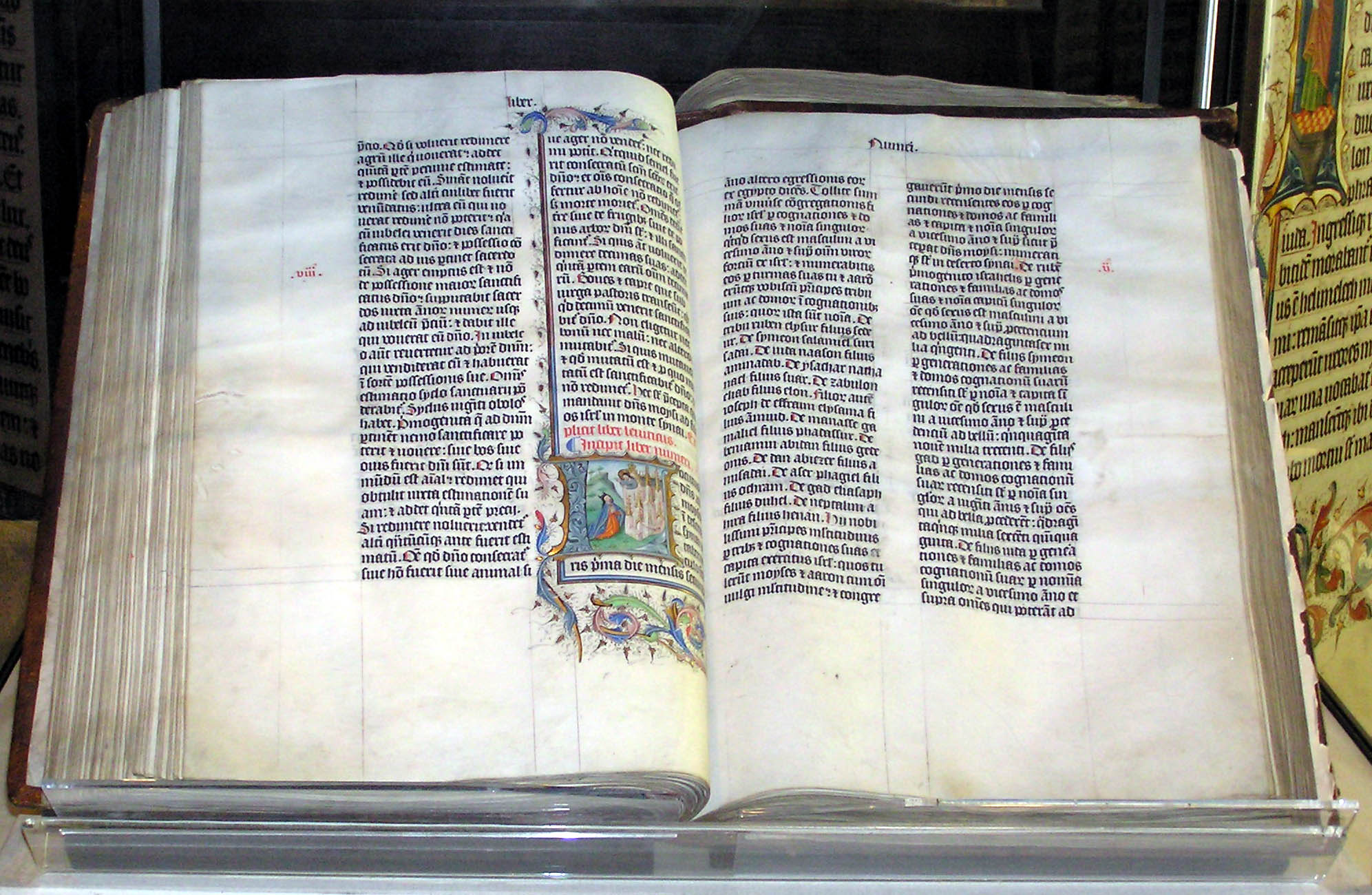

The biblical apocrypha (from Ancient Greek ἀπόκρυφος (apókruphos) 'hidden') denotes the collection of apocryphal ancient books thought to have been written some time between 200 BCE and 100 CE.[1][2][3][4][5]

This article is about a class of books covering the Old Testament era that are included in some Bibles. For lists of books accepted by different major churches, see Biblical canon § Old Testament table. For books whose canonicity is disputed by Protestant denominations, see Deuterocanonical books. For other books generally excluded from the canonical Hebrew Bible, see Old Testament pseudepigrapha. For the apocryphal writings of the New Testament, see New Testament apocrypha.The Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches include some or all of the same texts within the body of their version of the Old Testament, with Catholics terming them deuterocanonical books.[6] Traditional 80-book Protestant Bibles include fourteen books in an intertestamental section between the Old Testament and New Testament called the Apocrypha, deeming these useful for instruction, but non-canonical.[7][8][9][10]

Acceptance[edit]

The term apocryphal had been in use since the 5th century, and generally denotes obscure or pseudepigraphic material of dubious historicity or orthodoxy, as could be evidenced for example by being written in Greek rather than Hebrew.

It was in Luther's Bible of 1534 that the Apocrypha was first published as a separate intertestamental section. The preface to the Apocrypha in the Geneva Bible claimed that while these books "were not received by a common consent to be read and expounded publicly in the Church", and did not serve "to prove any point of Christian religion save in so much as they had the consent of the other scriptures called canonical to confirm the same", nonetheless, "as books proceeding from godly men they were received to be read for the advancement and furtherance of the knowledge of history and for the instruction of godly manners."[11] Later, during the English Civil War, the Westminster Confession of 1647 excluded the Apocrypha from the canon and made no recommendation of the Apocrypha above "other human writings",[12] and this attitude toward the Apocrypha is represented by the decision of the British and Foreign Bible Society in the early 19th century not to print it. Today, "English Bibles with the Apocrypha are becoming more popular again" and they are often printed as intertestamental books.[8]

Many of these texts are considered canonical Old Testament books by the Catholic Church, affirmed by the Council of Rome (382) and later reaffirmed by the Council of Trent (1545–1563); and by the Eastern Orthodox Church which are referred to as anagignoskomena per the Synod of Jerusalem (1672). The Anglican Communion accepts "the Apocrypha for instruction in life and manners, but not for the establishment of doctrine (Article VI in the Thirty-Nine Articles)",[13] and many "lectionary readings in The Book of Common Prayer are taken from the Apocrypha", with these lessons being "read in the same ways as those from the Old Testament".[14] The first Methodist liturgical book, The Sunday Service of the Methodists, employs verses from the Apocrypha, such as in the Eucharistic liturgy.[15] The Protestant Apocrypha contains three books (1 Esdras, 2 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh) that are accepted by many Eastern Orthodox Churches and Oriental Orthodox Churches as canonical, but are regarded as non-canonical by the Catholic Church and are therefore not included in modern Catholic Bibles.[16]

To this date, the Apocrypha are "included in the lectionaries of Anglican and Lutheran Churches".[17] Anabaptists use the Luther Bible, which contains the Apocrypha as intertestamental books; Amish wedding ceremonies include "the retelling of the marriage of Tobias and Sarah in the Apocrypha".[18] Moreover, the Revised Common Lectionary, in use by most mainline Protestants including Methodists and Moravians, lists readings from the Apocrypha in the liturgical calendar, although alternate Old Testament scripture lessons are provided.[19]

Technically, a pseudepigraphon is a book written in a biblical style and ascribed to an author who did not write it. In common usage, however, the term pseudepigrapha is often used by way of distinction to refer to apocryphal writings that do not appear in printed editions of the Bible, as opposed to the texts listed above. Examples[54] include:

Often included among the pseudepigrapha are 3 and 4 Maccabees because they are not traditionally found in western Bibles, although they are in the Septuagint. Similarly, the Book of Enoch, Book of Jubilees and 4 Baruch are often listed with the pseudepigrapha although they are commonly included in Ethiopian Bibles. The Psalms of Solomon are found in some editions of the Septuagint.

Texts

Commentaries

Introductions