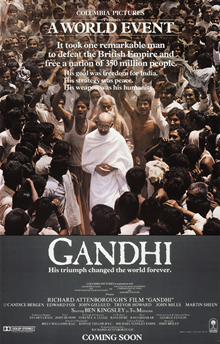

Gandhi (film)

Gandhi is a 1982 epic biographical film based on the life of Mahatma Gandhi, a major leader in the Indian independence movement against the British Empire during the 20th century. A co-production between India and the United Kingdom, the film was directed and produced by Richard Attenborough from a screenplay written by John Briley. It stars Ben Kingsley in the title role. The biographical film covers Gandhi's life from a defining moment in 1893, as he is thrown off a South African train for being in a whites-only compartment and concludes with his assassination and funeral in 1948. Although a practising Hindu, Gandhi's embracing of other faiths, particularly Christianity and Islam, is also depicted.

Gandhi

Richard Attenborough

- Goldcrest Films

- International Film Investors

- National Film Development Corporation of India

- Indo-British Films

Columbia Pictures (through Columbia-EMI-Warner Distributors in the United Kingdom[1])

- 30 November 1982 (New Delhi)

- 3 December 1982 (United Kingdom)

191 minutes[1]

- United Kingdom

- India

- English

- Hindi

$22 million[2]

$127.8 million[2]

Gandhi was released by Columbia Pictures in India on 30 November 1982, in the United Kingdom on 3 December, and in the United States on 8 December. It was praised for providing a historically accurate portrayal of the life of Gandhi, the Indian independence movement and the deleterious results of British colonisation on India. Its production values, costume design, and Kingsley's performance received worldwide critical acclaim. It became a commercial success, grossing $127.8 million on a $22 million budget. Gandhi received a leading eleven nominations at the 55th Academy Awards, winning eight, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor (for Kingsley). The British Film Institute ranked it as the 34th greatest British film of the 20th century. The American Film Institute ranked the film #29 on its list of most inspiring movies.

Plot[edit]

On 30 January 1948,[3] on his way to an evening prayer service, an elderly Gandhi is helped out for his evening walk to meet a large number of greeters and admirers. One visitor, Nathuram Godse, shoots him point blank in the chest. His state funeral is shown, the procession attended by millions of people from all walks of life, with a radio reporter speaking eloquently about Gandhi's world-changing life and works.

In June 1893, the 23-year-old Gandhi is thrown off a South African train for being an Indian sitting in a first-class compartment, despite him having a first-class ticket.[4] Realising the laws are biased even against well-educated and successful Indians, he then decides to start a non-violent protest campaign for the rights of all Indians in South Africa, arguing that they are British subjects and entitled to the same rights and privileges as whites. After numerous arrests and unwelcome international attention, the government finally relents by recognising some rights for Indians.[5]

In 1915, as a result of his victory in South Africa, Gandhi is invited back to India, where he is now considered something of a national hero. He is urged to take up the fight for India's independence (Swaraj, Quit India) from the British Empire. Gandhi agrees, and mounts a non-violent non-cooperation campaign of unprecedented scale, coordinating millions of Indians nationwide. There are some setbacks, such as violence against the protesters or by the protesters themselves, Gandhi's occasional imprisonment, and the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar.

Nevertheless, the campaign generates great attention, and Britain faces intense public pressure. In 1930, Gandhi protests against the British-imposed salt tax via a highly symbolic Salt March. He also travels to London for a conference concerning Britain's possible departure from India; this, however, proves fruitless. Gandhi spends much of the Second World War in prison for not supporting the war. During a period under house arrest, his wife Kasturba dies. After the war ends,[6] India finally wins its independence.[7] Indians celebrate this victory, but their troubles are far from over. The country is subsequently partitioned by religion. It is decided that the northwest area and the eastern part of India (current-day Bangladesh), both places where Muslims are in the majority, will become a new country called Pakistan. It is hoped that by permitting the Muslims to live in a separate country, violence will abate. Gandhi is opposed to the idea and is even willing to allow Muhammad Ali Jinnah to become the first Prime Minister of India,[8] but the Partition of India is carried out nevertheless. Religious tensions between Hindus and Muslims erupt into nationwide violence. Repulsed by this sudden unrest, Gandhi declares a hunger strike, in which he will not eat until the fighting stops.[9] The fighting does stop eventually.

Gandhi spends his last days trying to bring about peace between both nations. He, thereby, angers many dissidents on both sides, one of whom (Godse) is involved in a conspiracy to assassinate him.[10] Gandhi is cremated and his ashes are scattered on the Ganges.[11] As this happens, viewers hear Gandhi in another voiceover from earlier in the film.

Release[edit]

Gandhi premiered in New Delhi, India on 30 November 1982. Two days later, on 2 December, it had a Royal Premiere at the Odeon Leicester Square in London[24] in the presence of Prince Charles and Princess Diana before opening to the public the following day.[25][26] The film had a limited release in the US starting on Wednesday, 8 December 1982, followed by a wider release in January 1983.[2] In February 1983 it opened on two screens in India as well as opening nationwide in the UK and expanding into other countries.[27]

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Reviews were broadly positive not only in India but also internationally.[28] The film was discussed or reviewed in Newsweek,[21] Time,[29] the Washington Post,[30][31] The Public Historian,[32] Cross Currents,[33] The Journal of Asian Studies,[34] Film Quarterly,[35] The Progressive,[36] The Christian Century[36] and elsewhere.[37] Ben Kingsley's performance was especially praised. Among the few who took a more negative view of the film, historian Lawrence James called it "pure hagiography"[38] while anthropologist Akhil Gupta said it "suffers from tepid direction and a superficial and misleading interpretation of history."[39] Also Indian novelist Makarand R. Paranjape has written that "Gandhi, though hagiographical, follow a mimetic style of film-making in which cinema, the visual image itself, is supposed to portray or reflect 'reality'".[40] The film was also criticised by some right-wing commentators who objected to the film's advocacy of nonviolence, including Pat Buchanan, Emmett Tyrrell, and especially Richard Grenier.[36][41] In Time, Richard Schickel wrote that in portraying Gandhi's "spiritual presence... Kingsley is nothing short of astonishing."[29]: 97 A "singular virtue" of the film is that "its title figure is also a character in the usual dramatic sense of the term." Schickel viewed Attenborough's directorial style as having "a conventional handsomeness that is more predictable than enlivening," but this "stylistic self-denial serves to keep one's attention fastened where it belongs: on a persuasive, if perhaps debatable vision of Gandhi's spirit, and on the remarkable actor who has caught its light in all its seasons."[29]: 97 Roger Ebert gave the film four stars and called it a "remarkable experience",[42] and placed it 5th on his 10 best films of 1983.[43]

In Newsweek, Jack Kroll stated that "There are very few movies that absolutely must be seen. Sir Richard Attenborough's Gandhi is one of them."[21] The movie "deals with a subject of great importance... with a mixture of high intelligence and immediate emotional impact... [and] Ben Kingsley... gives what is possibly the most astonishing biographical performance in screen history." Kroll stated that the screenplay's "least persuasive characters are Gandhi's Western allies and acolytes" such as an English cleric and an American journalist, but that "Attenborough's 'old-fashioned' style is exactly right for the no-tricks, no-phony-psychologizing quality he wants."[21] Furthermore, Attenborough