Partition of India

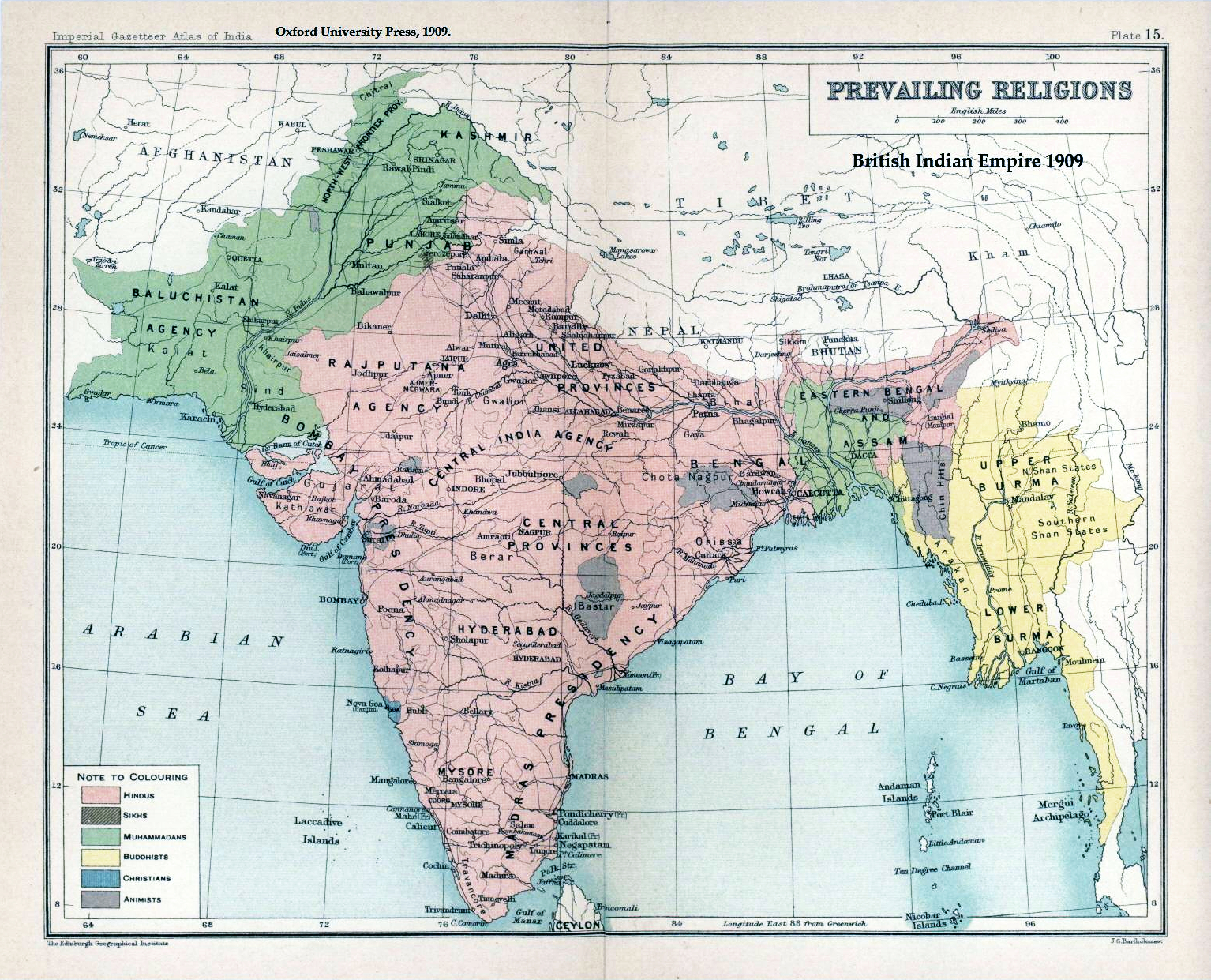

The Partition of India in 1947 was the change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in the Indian subcontinent and the creation of two independent dominions in South Asia: India and Pakistan.[1][2] The Dominion of India is today the Republic of India, and the Dominion of Pakistan—which at the time comprised two regions lying on either side of India—is now the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the People's Republic of Bangladesh. The partition was outlined in the Indian Independence Act 1947.[3] The change of political borders notably included the division of two provinces of British India,[a] Bengal and Punjab.[4] The majority Muslim districts in these provinces were awarded to Pakistan and the majority non-Muslim to India. The other assets that were divided included the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the Royal Indian Air Force, the Indian Civil Service, the railways, and the central treasury. Provisions for self-governing independent Pakistan and India legally came into existence at midnight on 14 and 15 August 1947 respectively.[5]

Date

14–15 August 1947

Two-nation theory: Muslim league's demand for separate Islamic nation, Indian Independence Act 1947

Partition of British India into two independent Dominions, India and Pakistan, sectarian violence, religious cleansing, and refugee crises

1 million

10–20 million

The partitioning of India was due to the demand of Muhammad Ali Jinnah seeking a separate homeland for Muslims; Jinnah had said in a speech in Lahore leading up to the partition, that Hindus and Muslims belong to two different religious philosophies, social customs and literary traditions, neither intermarrying nor eating together, belonging to two different civilisations whose ideas and conceptions are incompatible.[6][7][8]

The partition caused large-scale loss of life and an unprecedented migration between the two dominions.[9] Among refugees who survived, it solidified the belief that safety lay among co-religionists. In the instance of Pakistan, it made palpable a hitherto only-imagined refuge for the Muslims of British India.[10] The migrations took place hastily and with little warning. It is thought that between 14 million and 18 million people moved, and perhaps more. Excess mortality during the period of the partition is usually estimated to have been around one million.[11] The violent nature of the partition created an atmosphere of hostility and suspicion between India and Pakistan that affects their relationship to this day.

The term partition of India does not cover:

Nepal and Bhutan signed treaties with the British designating them as independent states and were not a part of British-ruled India.[12] The Himalayan Kingdom of Sikkim was established as a princely state after the Anglo-Sikkimese Treaty of 1861, but its sovereignty had been left undefined.[13] In 1947, Sikkim became an independent kingdom under the suzerainty of India. The Maldives became a protectorate of the British crown in 1887 and gained its independence in 1965.

Resettlement of refugees: 1947–1951[edit]

Resettlement in India[edit]

According to the 1951 Census of India, 2% of India's population were refugees (1.3% from West Pakistan and 0.7% from East Pakistan).

The majority of Hindu and Sikh Punjabi refugees from West Punjab were settled in Delhi and East Punjab (including Haryana and Himachal Pradesh). Delhi received the largest number of refugees for a single city, with the population of Delhi showing an increase from under 1 million (917,939) in the Census of India, 1941, to a little less than 2 million (1,744,072) in the 1951 Census, despite a large number of Muslims leaving Delhi in 1947 to go to Pakistan whether voluntarily or by coercion.[163] The incoming refugees were housed in various historical and military locations such as the Purana Qila, Red Fort, and military barracks in Kingsway Camp (around the present Delhi University). The latter became the site of one of the largest refugee camps in northern India, with more than 35,000 refugees at any given time besides Kurukshetra camp near Panipat. The campsites were later converted into permanent housing through extensive building projects undertaken by the Government of India from 1948 onwards. Many housing colonies in Delhi came up around this period, like Lajpat Nagar, Rajinder Nagar, Nizamuddin East, Punjabi Bagh, Rehgar Pura, Jangpura, and Kingsway Camp. Several schemes such as the provision of education, employment opportunities, and easy loans to start businesses were provided for the refugees at the all-India level.[164] Many Punjabi Hindu refugees were also settled in Cities of Western and Central Uttar Pradesh. A Colony consisting largely of Sikhs and Punjabi Hindus was also founded in Central Mumbai's Sion Koliwada region, and named Guru Tegh Bahadur Nagar.[165]

Hindus fleeing from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) were settled across Eastern, Central and Northeastern India, many ending up in neighbouring Indian states such as West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura. Substantial number of refugees were also settled in Madhya Pradesh (incl. Chhattisgarh) Bihar (incl. Jharkhand), Odisha and Andaman islands (where Bengalis today form the largest linguistic group)[166][167]

Sindhi Hindus settled predominantly in Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan. Substantial, however, were also settled in Madhya Pradesh, A few also settled in Delhi. A new township was established for Sindhi Hindu refugees in Maharashtra. The Governor-General of India, Sir Rajagopalachari, laid the foundation for this township and named it Ulhasnagar ('city of joy').

Substantial communities of Hindu Gujarati and Marathi Refugees who had lived in cities of Sindh and Southern Punjab were also resettled in Cities of Modern-day Gujarat and Maharashtra.[144][168]

A small community of Pashtun Hindus from Loralai, Balochistan was also settled City of Jaipur. Today they number around 1,000.[169]

Missing people[edit]

A study of the total population inflows and outflows in the districts of Punjab, using the data provided by the 1931 and 1951 Census has led to an estimate of 1.3 million missing Muslims who left western India but did not reach Pakistan.[126] The corresponding number of missing Hindus/Sikhs along the western border is estimated to be approximately 0.8 million.[174] This puts the total of missing people, due to partition-related migration along the Punjab border, to around 2.2 million.[174] Another study of the demographic consequences of partition in the Punjab region using the 1931, 1941 and 1951 censuses concluded that between 2.3 and 3.2 million people went missing in the Punjab.[175]

Post-partition migration[edit]

Pakistan[edit]

Due to Religious persecution in India persecution of Muslims in India, even after the 1951 Census, many Muslim families from India continued migrating to Pakistan throughout the 1950s and the early 1960s. According to historian Omar Khalidi, the Indian Muslim migration to West Pakistan between December 1947 and December 1971 was from Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala. The next stage of migration was between 1973 and the 1990s, and the primary destination for these migrants was Karachi and other urban centres in Sindh.[180]

In 1959, the International Labour Organization (ILO) published a report stating that from 1951 to 1956, a total of 650,000 Muslims from India relocated to West Pakistan.[180] However, Visaria (1969) raised doubts about the authenticity of the claims about Indian Muslim migration to Pakistan, since the 1961 Census of Pakistan did not corroborate these figures. However, the 1961 Census of Pakistan did incorporate a statement suggesting that there had been a migration of 800,000 people from India to Pakistan throughout the previous decade.[181] Of those who left for Pakistan, most never came back.

Indian Muslim migration to Pakistan declined drastically in the 1970s, a trend noticed by the Pakistani authorities. In June 1995, Pakistan's interior minister, Naseerullah Babar, informed the National Assembly that between the period of 1973–1994, as many as 800,000 visitors came from India on valid travel documents. Of these only 3,393 stayed.[180] In a related trend, intermarriages between Indian and Pakistani Muslims have declined sharply. According to a November 1995 statement of Riaz Khokhar, the Pakistani High Commissioner in New Delhi, the number of cross-border marriages has dropped from 40,000 a year in the 1950s and 1960s to barely 300 annually.[180]

In the aftermath of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, 3,500 Muslim families migrated from the Indian part of the Thar Desert to the Pakistani section of the Thar Desert.[182] 400 families were settled in Nagar after the 1965 war and an additional 3000 settled in the Chachro taluka in Sindh province of West Pakistan.[183] The government of Pakistan provided each family with 12 acres of land. According to government records, this land totalled 42,000 acres.[183]

The 1951 census in Pakistan recorded 671,000 refugees in East Pakistan, the majority of which came from West Bengal. The rest were from Bihar.[184] According to the ILO in the period 1951–1956, half a million Indian Muslims migrated to East Pakistan.[180] By 1961 the numbers reached 850,000. In the aftermath of the riots in Ranchi and Jamshedpur, Biharis continued to migrate to East Pakistan well into the late sixties and added up to around a million.[185] Crude estimates suggest that about 1.5 million Muslims migrated from West Bengal and Bihar to East Bengal in the two decades after partition.[186]

India[edit]

Due to religious persecution in Pakistan, Hindus continue to flee to India. Most of them tend to settle in the state of Rajasthan in India.[187] According to data of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan, just around 1,000 Hindu families fled to India in 2013.[187] In May 2014, a member of the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), Ramesh Kumar Vankwani, revealed in the National Assembly of Pakistan that around 5,000 Hindus are migrating from Pakistan to India every year.[188] Since India is not a signatory to the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention, it refuses to recognise Pakistani Hindu migrants as refugees.[187]

The population in the Tharparkar district in the Sindh province of West Pakistan was 80% Hindu and 20% Muslim at the time of independence in 1947. During the Indo-Pakistani Wars of 1965 and 1971, an estimated 1,500 Hindu families fled to India, which led to a massive demographic shift in the district.[182][189] During these same wars, 23,300 Hindu families also migrated to Jammu Division from Azad Kashmir and West Punjab.[190]

The migration of Hindus from East Pakistan to India continued unabated after partition. The 1951 census in India recorded that 2.5 million refugees arrived from East Pakistan, of which 2.1 million migrated to West Bengal while the rest migrated to Assam, Tripura, and other states.[184] These refugees arrived in waves and did not come solely at partition. By 1973, their number reached over 6 million. The following data displays the major waves of refugees from East Pakistan and the incidents which precipitated the migrations:[191][192]

Documentation efforts and oral history[edit]

In 2010, a Berkeley, California and Delhi, India-based non-profit organization, The 1947 Partition Archive, began documenting oral histories from those who lived through the partition and consolidated the interviews into an archive.[194] As of June 2021, nearly 9,700 interviews are preserved from 18 countries and are being released in collaboration with five university libraries in India and Pakistan, including Ashoka University, Habib University, Lahore University of Management Sciences, Guru Nanak Dev University and Delhi University in collaboration with Tata Trusts.[195]

In August 2017, The Arts and Cultural Heritage Trust (TAACHT) of United Kingdom set up what they describe as "the world's first Partition Museum" at Town Hall in Amritsar, Punjab. The Museum, which is open from Tuesday to Sunday, offers multimedia exhibits and documents that describe both the political process that led to partition and carried it forward, and video and written narratives offered by survivors of the events.[196]

A 2019 book by Kavita Puri, Partition Voices: Untold British Stories, based on the BBC Radio 4 documentary series of the same name, includes interviews with about two dozen people who witnessed partition and subsequently migrated to Britain.[197][198]