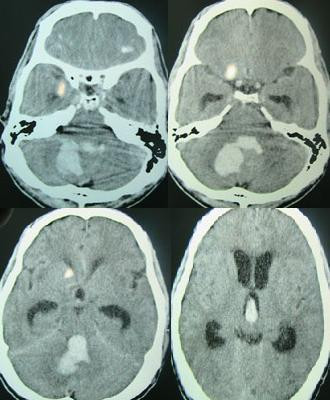

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as hemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into the tissues of the brain (i.e. the parenchyma), into its ventricles, or into both.[3][4][1] An ICH is a type of bleeding within the skull and one kind of stroke (ischemic stroke being the other).[3][4] Symptoms can vary dramatically depending on the severity (how much blood), acuity (over what timeframe), and location (anatomically) but can include headache, one-sided weakness, numbness, tingling, or paralysis, speech problems, vision or hearing problems, memory loss, attention problems, coordination problems, balance problems, dizziness or lightheadedness or vertigo, nausea/vomiting, seizures, decreased level of consciousness or total loss of consciousness, neck stiffness, and fever.[2][1]

Intracerebral hemorrhage

Cerebral haemorrhage, cerebral hemorrhage, intra-axial hemorrhage, cerebral hematoma, cerebral bleed, brain bleed, hemorrhagic stroke

Headache, one-sided numbness, weakness, tingling, or paralysis, speech problems, vision or hearing problems, dizziness or lightheadedness or vertigo, nausea/vomiting, seizures, decreased level or total loss of consciousness, neck stiffness, memory loss, attention and coordination problems, balance problems, fever, shortness of breath (when bleed is in the brain stem) [1][2]

Coma, persistent vegetative state, cardiac arrest (when bleeding is severe or in the brain stem), death

Blood pressure control, surgery, ventricular drain[1]

20% good outcome[2]

2.5 per 10,000 people a year[2]

44% die within one month[2]

Hemorrhagic stroke may occur on the background of alterations to the blood vessels in the brain, such as cerebral arteriolosclerosis, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral arteriovenous malformation, brain trauma, brain tumors and an intracranial aneurysm, which can cause intraparenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhage.[1]

The biggest risk factors for spontaneous bleeding are high blood pressure and amyloidosis.[2] Other risk factors include alcoholism, low cholesterol, blood thinners, and cocaine use.[2] Diagnosis is typically by CT scan.[1]

Treatment should typically be carried out in an intensive care unit due to strict blood pressure goals and frequent use of both pressors and antihypertensive agents.[1][5] Anticoagulation should be reversed if possible and blood sugar kept in the normal range.[1] A procedure to place an external ventricular drain may be used to treat hydrocephalus or increased intracranial pressure, however, the use of corticosteroids is frequently avoided.[1] Sometimes surgery to directly remove the blood can be therapeutic.[1]

Cerebral bleeding affects about 2.5 per 10,000 people each year.[2] It occurs more often in males and older people.[2] About 44% of those affected die within a month.[2] A good outcome occurs in about 20% of those affected.[2] Intracerebral hemorrhage, a type of hemorrhagic stroke, was first distinguished from ischemic strokes due to insufficient blood flow, so called "leaks and plugs", in 1823.[6]

Epidemiology[edit]

The incidence of intracerebral hemorrhage is estimated at 24.6 cases per 100,000 person years with the incidence rate being similar in men and women.[7][8] The incidence is much higher in the elderly, especially those who are 85 or older, who are 9.6 times more likely to have an intracerebral hemorrhage as compared to those of middle age.[8] It accounts for 20% of all cases of cerebrovascular disease in the United States, behind cerebral thrombosis (40%) and cerebral embolism (30%).[9]

Types[edit]

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage[edit]

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage (IPH) is one form of intracerebral bleeding in which there is bleeding within brain parenchyma.[10] Intraparenchymal hemorrhage accounts for approximately 8-13% of all strokes and results from a wide spectrum of disorders. It is more likely to result in death or major disability than ischemic stroke or subarachnoid hemorrhage, and therefore constitutes an immediate medical emergency. Intracerebral hemorrhages and accompanying edema may disrupt or compress adjacent brain tissue, leading to neurological dysfunction. Substantial displacement of brain parenchyma may cause elevation of intracranial pressure (ICP) and potentially fatal herniation syndromes.

Intraventricular hemorrhage[edit]

Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), also known asintraventricular bleeding, is a bleeding into the brain's ventricular system, where the cerebrospinal fluid is produced and circulates through towards the subarachnoid space. It can result from physical trauma or from hemorrhagic stroke.

30% of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) are primary, confined to the ventricular system and typically caused by intraventricular trauma, aneurysm, vascular malformations, or tumors, particularly of the choroid plexus.[11] However 70% of IVH are secondary in nature, resulting from an expansion of an existing intraparenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhage.[11] Intraventricular hemorrhage has been found to occur in 35% of moderate to severe traumatic brain injuries.[12] Thus the hemorrhage usually does not occur without extensive associated damage, and so the outcome is rarely good.[13][14]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

People with intracerebral bleeding have symptoms that correspond to the functions controlled by the area of the brain that is damaged by the bleed.[15] These localizing signs and symptoms can include hemiplegia (or weakness localized to one side of the body) and paresthesia (loss of sensation) including hemisensory loss (if localized to one side of the body).[7] These symptoms are usually rapid in onset, sometimes occurring in minutes, but not as rapid as the symptom onset in ischemic stroke.[7] While the duration of onset not be as rapid, it is important that patients go to the emergency department as soon as they notice any symptoms as early detection and management of stroke may lead to better outcomes post-stroke than delayed identification.[16]

A mnemonic to remember the warning signs of stroke is FAST (facial droop, arm weakness, speech difficulty, and time to call emergency services),[17] as advocated by the Department of Health (United Kingdom) and the Stroke Association, the American Stroke Association, the National Stroke Association (US), the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)[18] and the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS).[19] Use of these scales is recommended by professional guidelines.[20] FAST is less reliable in the recognition of posterior circulation stroke.[21]

Other symptoms include those that indicate a rise in intracranial pressure caused by a large mass (due to hematoma expansion) putting pressure on the brain.[15] These symptoms include headaches, nausea, vomiting, a depressed level of consciousness, stupor and death.[7] Continued elevation in the intracranial pressure and the accompanying mass effect may eventually cause brain herniation (when different parts of the brain are displaced or shifted to new areas in relation to the skull and surrounding dura mater supporting structures). Brain herniation is associated with hyperventilation, extensor rigidity, pupillary asymmetry, pyramidal signs, coma and death.[10]

Hemorrhage into the basal ganglia or thalamus causes contralateral hemiplegia due to damage to the internal capsule.[7] Other possible symptoms include gaze palsies or hemisensory loss.[7] Intracerebral hemorrhage into the cerebellum may cause ataxia, vertigo, incoordination of limbs and vomiting.[7] Some cases of cerebellar hemorrhage lead to blockage of the fourth ventricle with subsequent impairment of drainage of cerebrospinal fluid from the brain.[7] The ensuing hydrocephalus, or fluid buildup in the ventricles of the brain leads to a decreased level of consciousness, total loss of consciousness, coma, and persistent vegetative state.[7] Brainstem hemorrhage most commonly occurs in the pons and is associated with shortness of breath, cranial nerve palsies, pinpoint (but reactive) pupils, gaze palsies, facial weakness, coma, and persistent vegetative state (if there is damage to the reticular activating system).[7]

Intracerebral bleeds are the second most common cause of stroke, accounting for 10% of hospital admissions for stroke.[23] High blood pressure raises the risks of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage by two to six times.[22] More common in adults than in children, intraparenchymal bleeds are usually due to penetrating head trauma, but can also be due to depressed skull fractures. Acceleration-deceleration trauma,[24][25][26] rupture of an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation (AVM), and bleeding within a tumor are additional causes. Amyloid angiopathy is not an uncommon cause of intracerebral hemorrhage in patients over the age of 55. A very small proportion is due to cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

Risk factors for ICH include:[11]

Hypertension is the strongest risk factor associated with intracerebral hemorrhage and long term control of elevated blood pressure has been shown to reduce the incidence of hemorrhage.[7] Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, a disease characterized by deposition of amyloid beta peptides in the walls of the small blood vessels of the brain, leading to weakened blood vessel walls and an increased risk of bleeding; is also an important risk factor for the development of intracerebral hemorrhage. Other risk factors include advancing age (usually with a concomitant increase of cerebral amyloid angiopathy risk in the elderly), use of anticoagulants or antiplatelet medications, the presence of cerebral microbleeds, chronic kidney disease, and low low density lipoprotein (LDL) levels (usually below 70).[27][28] The direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) such as the factor Xa inhibitors or direct thrombin inhibitors are thought to have a lower risk of intracerebral hemorrhage as compared to the vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin.[7]

Cigarette smoking may be a risk factor but the association is weak.[29]

Traumautic intracerebral hematomas are divided into acute and delayed. Acute intracerebral hematomas occur at the time of the injury while delayed intracerebral hematomas have been reported from as early as 6 hours post injury to as long as several weeks.

Prognosis[edit]

About 8 to 33% of those with intracranial haemorrhage have neurological deterioration within the first 24 hours of hospital admission, where a large proportion of them happens within 6 to 12 hours. Rate of haematoma expansion, perihaematoma odema volume and the presence of fever can affect the chances of getting neurological complications.[47]

The risk of death from an intraparenchymal bleed in traumatic brain injury is especially high when the injury occurs in the brain stem.[48] Intraparenchymal bleeds within the medulla oblongata are almost always fatal, because they cause damage to cranial nerve X, the vagus nerve, which plays an important role in blood circulation and breathing.[24] This kind of hemorrhage can also occur in the cortex or subcortical areas, usually in the frontal or temporal lobes when due to head injury, and sometimes in the cerebellum.[24][49] Larger volumes of hematoma at hospital admission as well as greater expansion of the hematoma on subsequent evaluation (usually occurring within 6 hours of symptom onset) are associated with a worse prognosis.[7][50] Perihematomal edema, or secondary edema surrounding the hematoma, is associated with secondary brain injury, worsening neurological function and is associated with poor outcomes.[7] Intraventricular hemorrhage, or bleeding into the ventricles of the brain, which may occur in 30–50% of patients, is also associated with long-term disability and a poor prognosis.[7] Brain herniation is associated with poor prognoses.[7]

For spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage seen on CT scan, the death rate (mortality) is 34–50% by 30 days after the injury,[22] and half of the deaths occur in the first 2 days.[51] Even though the majority of deaths occur in the first few days after ICH, survivors have a long-term excess mortality rate of 27% compared to the general population.[52] Of those who survive an intracerebral hemorrhage, 12–39% are independent with regard to self-care; others are disabled to varying degrees and require supportive care.[8]