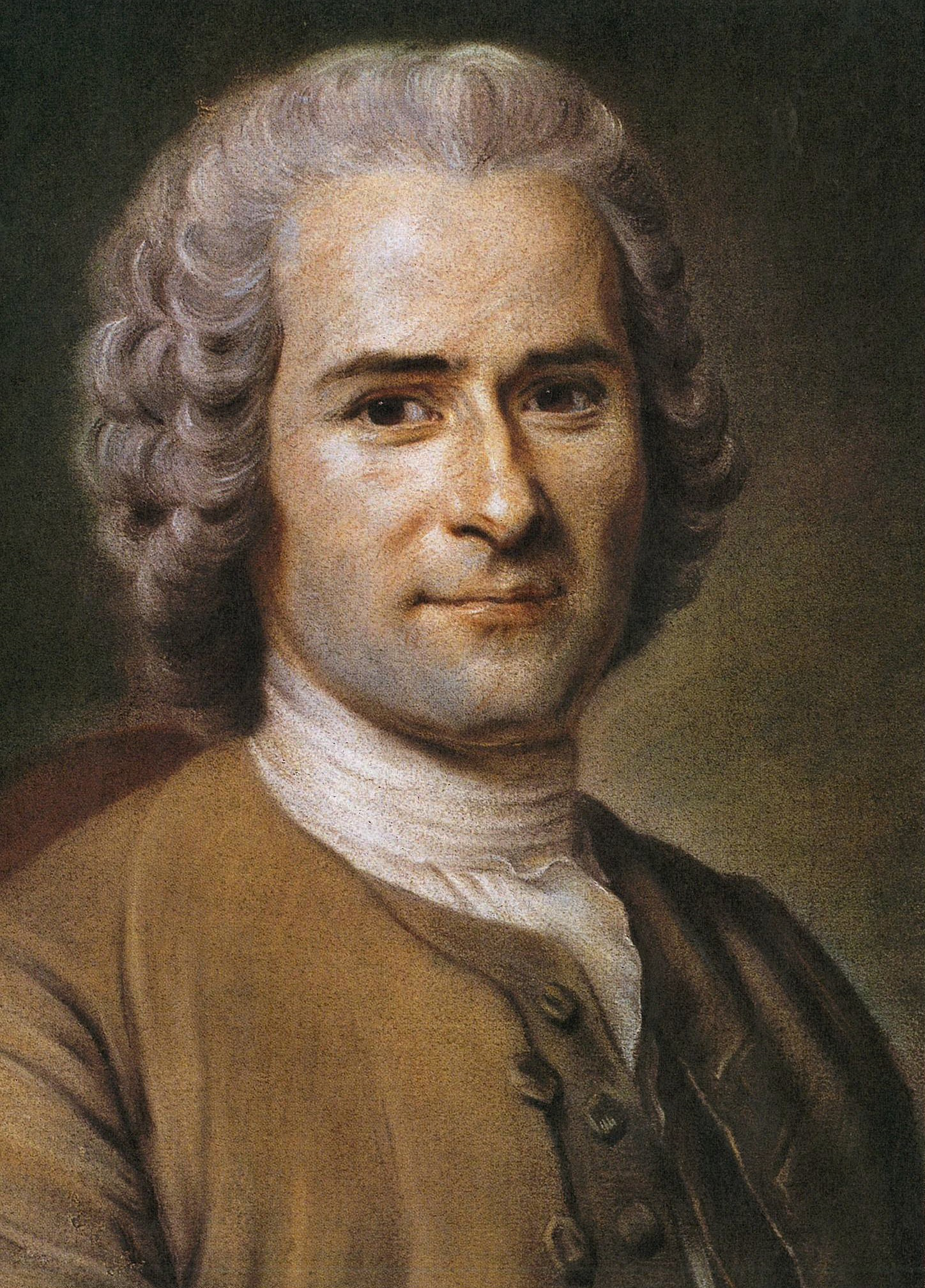

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (UK: /ˈruːsoʊ/, US: /ruːˈsoʊ/[1][2] French: [ʒɑ̃ ʒak ʁuso]; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher (philosophe), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolution and the development of modern political, economic, and educational thought.[3]

This article is about the philosopher. For the director, see Jean-Jacques Rousseau (director).

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

28 June 1712

2 July 1778 (aged 66)

Thérèse Levasseur (1745–1778)

Political philosophy, music, education, literature

French

Social change

from 1743

Académie de Dijon (1750)

His Discourse on Inequality, which argues that private property is the source of inequality, and The Social Contract, which outlines the basis for a legitimate political order, are cornerstones in modern political and social thought. Rousseau's sentimental novel Julie, or the New Heloise (1761) was important to the development of preromanticism and romanticism in fiction.[4][5] His Emile, or On Education (1762) is an educational treatise on the place of the individual in society. Rousseau's autobiographical writings—the posthumously published Confessions (completed in 1770), which initiated the modern autobiography, and the unfinished Reveries of the Solitary Walker (composed 1776–1778)—exemplified the late 18th-century "Age of Sensibility", and featured an increased focus on subjectivity and introspection that later characterized modern writing.

Biography[edit]

Youth[edit]

Rousseau was born in the Republic of Geneva, which was at the time a city-state and a Protestant associate of the Swiss Confederacy (now a canton of Switzerland). Since 1536, Geneva had been a Huguenot republic and the seat of Calvinism. Five generations before Rousseau, his ancestor Didier, a bookseller who may have published Protestant tracts, had escaped persecution from French Catholics by fleeing to Geneva in 1549, where he became a wine merchant.[6][7]

Philosophy[edit]

Influences[edit]

Rousseau later noted, that when he read the question for the essay competition of the Academy of Dijon, which he would go on to win: "Has the rebirth of the arts and sciences contributed to the purification of the morals?", he felt that "the moment I read this announcement I saw another universe and became a different man".[85] The essay he wrote in response led to one of the central themes of Rousseau's thought, which was that perceived social and cultural progress had in fact led only to the moral degradation of humanity.[86] His influences to this conclusion included Montesquieu, François Fénelon, Michel de Montaigne, Seneca the Younger, Plato, and Plutarch.[87]

Rousseau based his political philosophy on contract theory and his reading of Thomas Hobbes.[88] Reacting to the ideas of Samuel von Pufendorf and John Locke was also driving his thought.[89] All three thinkers had believed that humans living without central authority were facing uncertain conditions in a state of mutual competition.[89] In contrast, Rousseau believed that there was no explanation for why this would be the case, as there would have been no conflict or property.[90] Rousseau especially criticized Hobbes for asserting that since man in the "state of nature... has no idea of goodness he must be naturally wicked; that he is vicious because he does not know virtue". On the contrary, Rousseau holds that "uncorrupted morals" prevail in the "state of nature".[91]

Religion[edit]

Having converted to Roman Catholicism early in life and returned to the austere Calvinism of his native Geneva as part of his period of moral reform, Rousseau maintained a profession of that religious philosophy and of John Calvin as a modern lawgiver throughout the remainder of his life.[125] Unlike many of the more agnostic Enlightenment philosophers, Rousseau affirmed the necessity of religion. His views on religion presented in his works of philosophy, however, may strike some as discordant with the doctrines of both Catholicism and Calvinism.

Rousseau's strong endorsement of religious toleration, as expounded in Émile, was interpreted as advocating indifferentism, a heresy, and led to the condemnation of the book in both Calvinist Geneva and Catholic Paris. Although he praised the Bible, he was disgusted by the Christianity of his day.[126] Rousseau's assertion in The Social Contract that true followers of Christ would not make good citizens may have been another reason for his condemnation in Geneva. He also repudiated the doctrine of original sin, which plays a large part in Calvinism. In his "Letter to Beaumont", Rousseau wrote, "there is no original perversity in the human heart."[127]

In the 18th century, many deists viewed God merely as an abstract and impersonal creator of the universe, likened to a giant machine. Rousseau's deism differed from the usual kind in its emotionality. He saw the presence of God in the creation as good, and separate from the harmful influence of society. Rousseau's attribution of a spiritual value to the beauty of nature anticipates the attitudes of 19th-century Romanticism towards nature and religion. (Historians—notably William Everdell, Graeme Garrard, and Darrin McMahon—have additionally situated Rousseau within the Counter-Enlightenment.)[128][129] Rousseau was upset that his deism was so forcefully condemned, while those of the more atheistic philosophers were ignored. He defended himself against critics of his religious views in his "Letter to Mgr de Beaumont, the Archbishop of Paris", "in which he insists that freedom of discussion in religious matters is essentially more religious than the attempt to impose belief by force."[130]

Rousseau was a moderately successful composer of music, who wrote seven operas as well as music in other forms, and contributed to music theory. As a composer, his music was a blend of the late Baroque style and the emergent Classical fashion, i.e. Galant, and he belongs to the same generation of transitional composers as Christoph Willibald Gluck and C. P. E. Bach. One of his more well-known works is the one-act opera The Village Soothsayer. It contains the duet "Non, Colette n'est point trompeuse," which was later rearranged as a standalone song by Beethoven,[131] and the gavotte in scene no. 8 is the source of the tune of the folk song "Go Tell Aunt Rhody".[132] He also composed several noted motets, some of which were sung at the Concert Spirituel in Paris.[133] Rousseau's Aunt Suzanne was passionate about music and heavily influenced Rousseau's interest in music. In his Confessions, Rousseau claims he is "indebted" to her for his passion of music. Rousseau took formal instruction in music at the house of Françoise-Louise de Warens. She housed Rousseau on and off for about 13 years, giving him jobs and responsibilities.[134] In 1742, Rousseau developed a system of musical notation that was compatible with typography and numbered. He presented his invention to the Academie Des Sciences, but they rejected it, praising his efforts and pushing him to try again.[135] In 1743, Rousseau wrote his first opera, Les Muses galantes, which was first performed in 1745. Rousseau also developed a style of "boustrophedon" notation which would have music read in alternating directions (right to left for a second staff, and then left to right for the next staff for example) in an effort to allow musicians to not have to "jump" staffs while reading.[136]

Rousseau and Jean-Philippe Rameau argued over the superiority of Italian music over French.[135] Rousseau argued that Italian music was superior based on the principle that melody must have priority over harmony. Rameau argued that French music was superior based on the principle that harmony must have priority over melody. Rousseau's plea for melody introduced the idea that in art, the free expression of a creative person is more important than the strict adherence to traditional rules and procedures. This is known today as a characteristic of Romanticism.[137] Rousseau argued for musical freedom and changed people's attitudes towards music. His works were acknowledged by composers such as Christoph Willibald Gluck and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. After composing The Village Soothsayer in 1752, Rousseau felt he could not go on working for the theater because he was a moralist who had decided to break from worldly values.

Musical compositions