King James Version

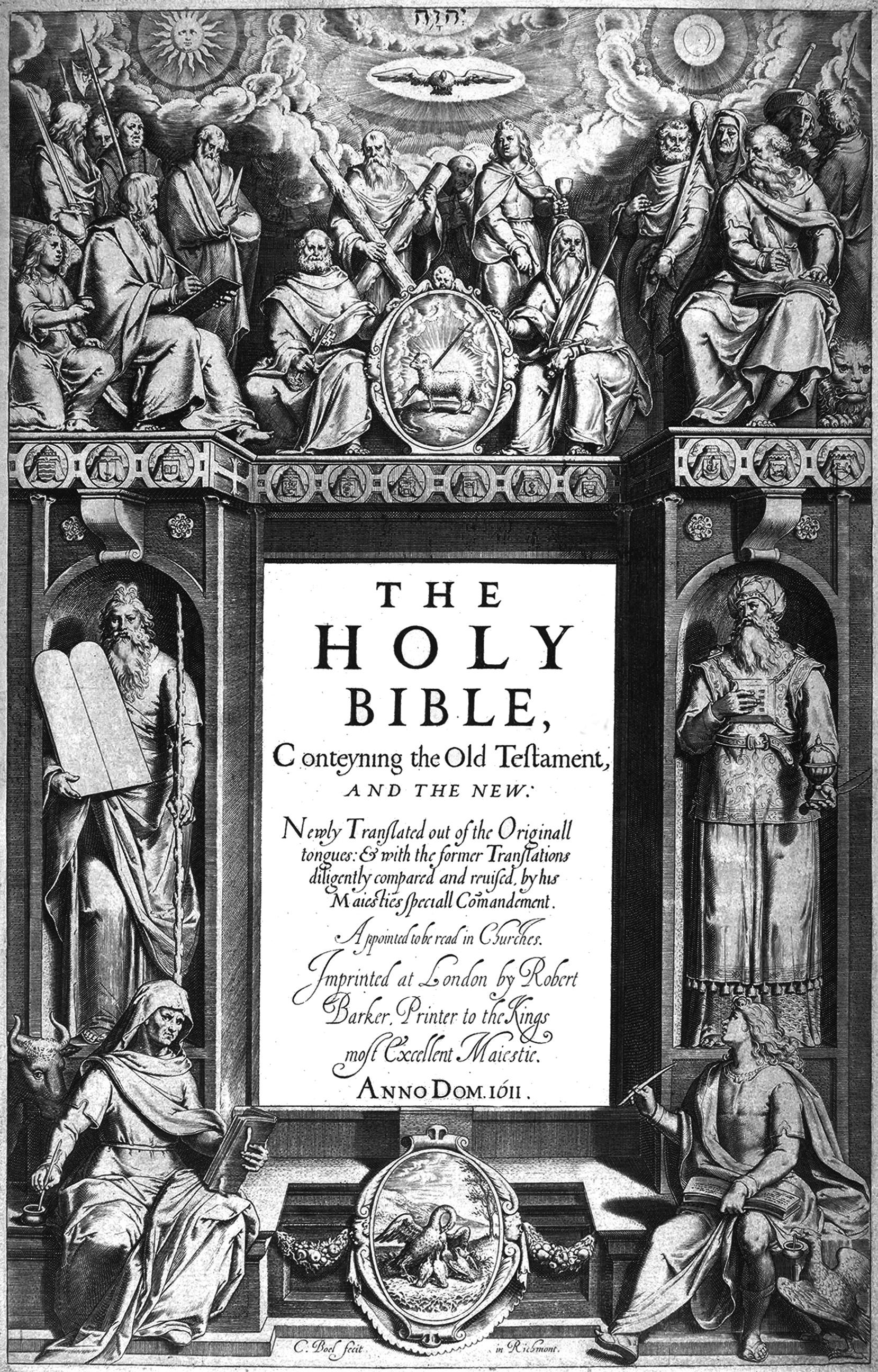

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of King James VI and I.[d][e] The 80 books of the King James Version include 39 books of the Old Testament, 14 books of Apocrypha, and the 27 books of the New Testament.

"KJB" redirects here. For other uses, see KJB (disambiguation) and King James Version (disambiguation).

Noted for its "majesty of style", the King James Version has been described as one of the most important books in English culture and a driving force in the shaping of the English-speaking world.[3][4] The King James Version remains the preferred translation of many Christian fundamentalists and religious movements, and it is considered one of the important literary accomplishments of early modern England.

The KJV was the third translation into English approved by the English Church authorities: The first had been the Great Bible (1535), and the second had been the Bishops' Bible (1568).[5] In Switzerland the first generation of Protestant Reformers had produced the Geneva Bible[6] which was published in 1560[7] having referred to the original Hebrew and Greek scriptures, which was influential in the writing of the Authorized King James Version.

The English Church initially used the officially sanctioned "Bishops' Bible", which was hardly used by the population. More popular was the named "Geneva Bible", which was created on the basis of the Tyndale translation in Geneva under the direct successor of the reformer John Calvin for his English followers. However, their footnotes represented a Calvinistic Puritanism that was too radical for James. The translators of the Geneva Bible had translated the word king as tyrant about four hundred times—the word tyrant does not appear once in the KJV. Because of this, it has been assumed King James purposely had the translators of the KJV translate the word tyrant as either "troubling", "oppressor", or some other word to avoid people being critical of his monarchy, though there is no evidence to back up that claim.[8] Arguably this more accurately reflects the difference in meaning between "tyrant" in ancient Greek and modern English.

James convened the Hampton Court Conference in January 1604, where a new English version was conceived in response to the problems of the earlier translations perceived by the Puritans,[9] a faction of the Church of England.[10] James gave translators instructions intended to ensure the new version would conform to the ecclesiology, and reflect the episcopal structure, of the Church of England and its belief in an ordained clergy.[11][12] In common with most other translations of the period, the New Testament was translated from Greek, the Old Testament from Hebrew and Aramaic, and the Apocrypha from Greek and Latin. In the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, the text of the Authorized Version replaced the text of the Great Bible for Epistle and Gospel readings, and as such was authorized by Act of Parliament.[13]

By the first half of the 18th century, the Authorized Version had become effectively unchallenged as the only English translation used in Anglican and other English Protestant churches, except for the Psalms and some short passages in the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England. Over the 18th century, the Authorized Version supplanted the Latin Vulgate as the standard version of scripture for English-speaking scholars. With the development of stereotype printing at the beginning of the 19th century, this version of the Bible had become the most widely printed book in history, almost all such printings presenting the standard text of 1769, and nearly always omitting the books of the Apocrypha. Today the unqualified title "King James Version" usually indicates this Oxford standard text.

Literary attributes[edit]

Marginal notes[edit]

In obedience to their instructions, the translators provided no marginal interpretation of the text, but in some 8,500 places a marginal note offers an alternative English wording.[133] The majority of these notes offer a more literal rendering of the original, introduced as "Heb", "Chal" (Chaldee, referring to Aramaic), "Gr" or "Lat". Others indicate a variant reading of the source text (introduced by "or"). Some of the annotated variants derive from alternative editions in the original languages, or from variant forms quoted in the fathers. More commonly, though, they indicate a difference between the literal original language reading and that in the translators' preferred recent Latin versions: Tremellius for the Old Testament, Junius for the Apocrypha, and Beza for the New Testament.[134] At thirteen places in the New Testament[135][136] a marginal note records a variant reading found in some Greek manuscript copies; in almost all cases reproducing a counterpart textual note at the same place in Beza's editions.[137]

A few more extensive notes clarify Biblical names and units of measurement or currency. Modern reprintings rarely reproduce these annotated variants—although they are to be found in the New Cambridge Paragraph Bible. In addition, there were originally some 9,000 scriptural cross-references, in which one text was related to another. Such cross-references had long been common in Latin Bibles, and most of those in the Authorized Version were copied unaltered from this Latin tradition. Consequently the early editions of the KJV retain many Vulgate verse references—e.g. in the numbering of the Psalms.[138] At the head of each chapter, the translators provided a short précis of its contents, with verse numbers; these are rarely included in complete form in modern editions.

Use of typeface[edit]

Also in obedience to their instructions, the translators indicated 'supplied' words in a different typeface; but there was no attempt to regularize the instances where this practice had been applied across the different companies; and especially in the New Testament, it was used much less frequently in the 1611 edition than would later be the case.[78] In one verse, 1 John 2:23, an entire clause was printed in roman type (as it had also been in the Great Bible and Bishop's Bible);[139] indicating a reading then primarily derived from the Vulgate, albeit one for which the later editions of Beza had provided a Greek text.[140]