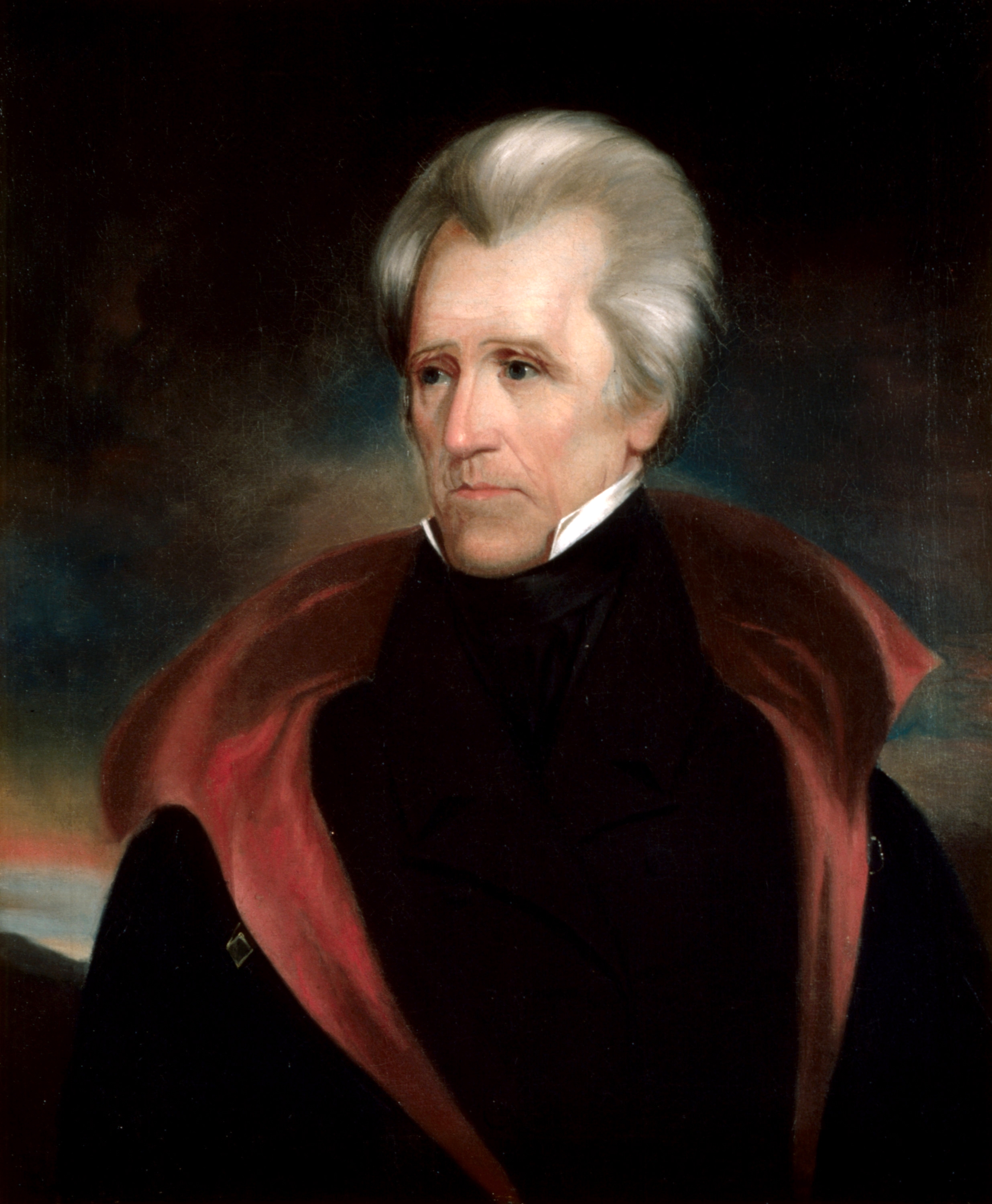

Presidency of Andrew Jackson

The presidency of Andrew Jackson began on March 4, 1829, when Andrew Jackson was inaugurated as President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1837. Jackson, the seventh United States president, took office after defeating incumbent President John Quincy Adams in the bitterly contested 1828 presidential election. During the 1828 presidential campaign, Jackson founded the political force that coalesced into the Democratic Party during Jackson's presidency. Jackson won re-election in 1832, defeating National Republican candidate Henry Clay by a wide margin. He was succeeded by his hand-picked successor, Vice President Martin Van Buren, after Van Buren won the 1836 presidential election.

"Age of Jackson" redirects here. For the Pulitzer Prize-winning book about this topic, see Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.Cabinet

Jackson's presidency saw several important developments in domestic policy. A strong supporter of the removal of Native American tribes from U.S. territory east of the Mississippi River, Jackson began the process of forced relocation known as the "Trail of Tears". He instituted the spoils system for federal government positions, using his patronage powers to build a powerful and united Democratic Party. In response to the nullification crisis, Jackson threatened to send federal soldiers into South Carolina, but the crisis was defused by the passage of the Tariff of 1833. He engaged in a long struggle with the Second Bank of the United States, which he viewed as an anti-democratic bastion of elitism. Jackson emerged triumphant in the "Bank War" and the federal charter of the Second Bank of the United States expired in 1836. The destruction of the bank and Jackson's hard money policies would contribute to the Panic of 1837. Foreign affairs were less eventful than domestic affairs during Jackson's presidency, but Jackson pursued numerous commercial treaties with foreign powers and recognized the independence of the Republic of Texas.

Jackson was the most influential and controversial political figure of the 1830s, and his two terms as president set the tone for the quarter-century era of American public discourse known as the Jacksonian Era. Historian James Sellers has stated that "Andrew Jackson's masterful personality was enough by itself to make him one of the most controversial figures ever to stride across the American stage".[1] His actions encouraged his political opponents to coalesce into the Whig Party, which favored the use of federal power to modernize the economy through support for banking, tariffs on manufactured imports, and internal improvements such as canals and harbors. Of all presidential reputations, Jackson's is perhaps the most difficult to summarize or explain. A generation after his presidency, biographer James Parton found his reputation a mass of contradictions: "he was dictator or democrat, ignoramus or genius, Satan or saint". Thirteen polls of historians and political scientists taken between 1948 and 2009 ranked Jackson always in or near the top ten presidents.[2]

Slavery controversies[edit]

A slave owner himself, Jackson favored the expansion of slavery into the territories and disapproved of anti-slavery agitation. Though slavery was not a major issue of Jackson's presidency, two notable controversies related to slavery arose while he was in the White House. In 1835, the American Anti-Slavery Society launched a mail campaign against the peculiar institution. Tens of thousands of antislavery pamphlets and tracts were sent to Southern destinations through the U.S. mail. Across the South, reaction to the abolition mail campaign bordered on apoplexy.[109] In Congress, Southerners demanded the prevention of delivery of the tracts, and Jackson moved to placate Southerners in the aftermath of the nullification crisis. Abolitionists decried Postmaster General Amos Kendall's decision to give Southern postmasters discretionary powers to discard the tracts as a suppression of free speech.[110]

Another conflict over slavery in 1835 ensued when abolitionists sent the U.S. House of Representatives petitions to end the slave trade and slavery in Washington, D.C.[111] These petitions infuriated pro-slavery Southerners, who attempted to prevent acknowledgement or discussion of the petitions. Northern Whigs objected that anti-slavery petitions were constitutional and should not be forbidden.[111] South Carolina Representative Henry L. Pinckney introduced a resolution that denounced the petitions as "sickly sentimentality", declared that Congress had no right to interfere with slavery, and tabled all further anti-slavery petitions. Southerners in Congress, including many of Jackson's supporters, favored the measure (the 21st Rule, commonly called the "gag rule"), which was passed quickly and without any debate, thus temporarily suppressing abolitionist activities in Congress.[111]

Two other important slavery-related developments occurred while Jackson was in office. In January 1831, William Lloyd Garrison established The Liberator, which emerged as the most influential abolitionist newspaper in the country. While many slavery opponents sought the gradual emancipation of all slaves, Garrison called for the immediate abolition of slavery throughout the country. Garrison also established the American Anti-Slavery Society, which grew to approximately 250,000 members by 1838.[112] In the same year that Garrison founded The Liberator, Nat Turner launched his slave rebellion. After killing dozens of whites in southeastern Virginia across two days, Turner's rebels were suppressed by a combination of vigilantes, the state militia, and federal soldiers.[113]