Jacksonian democracy

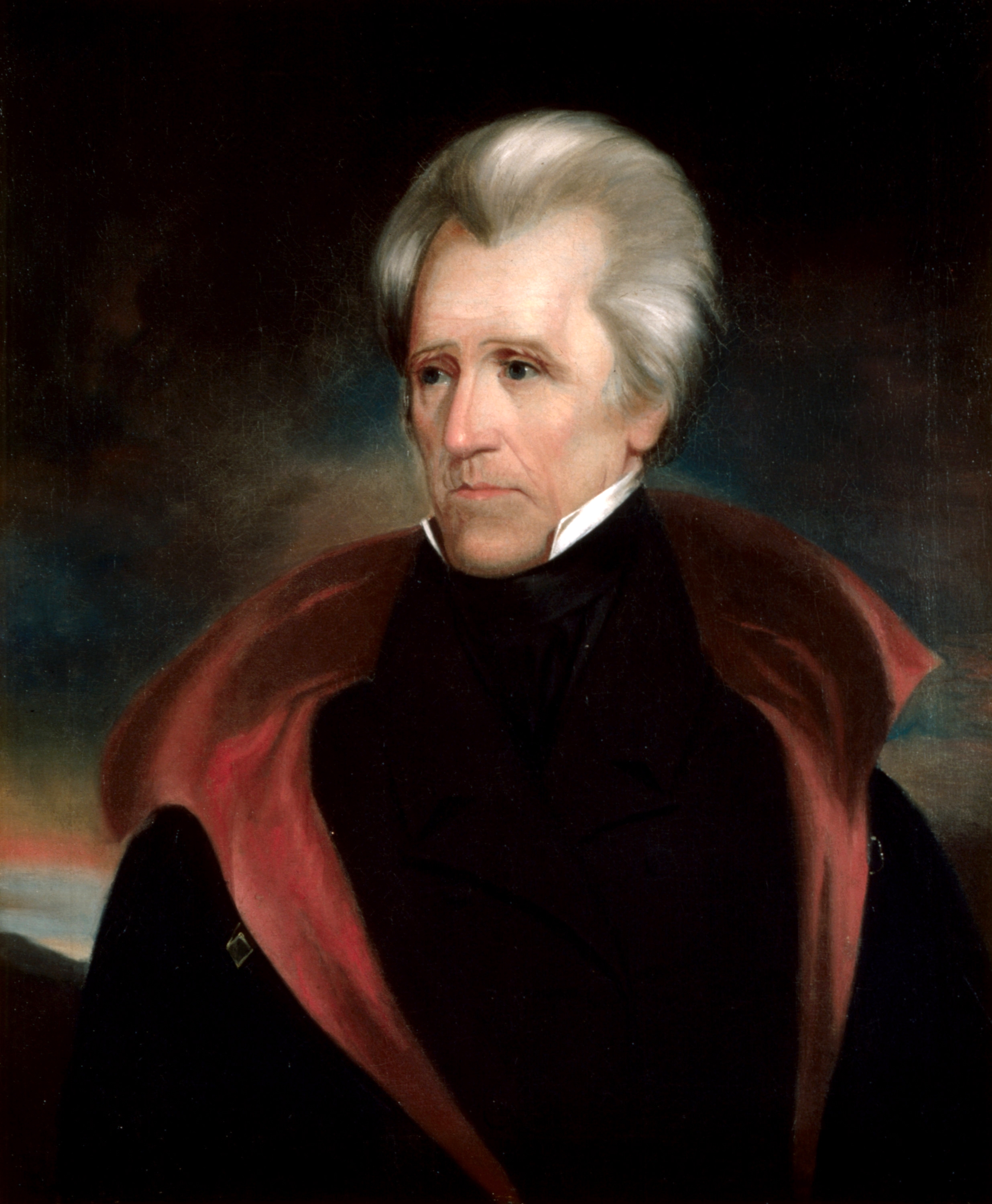

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21 and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, Andrew Jackson and his supporters, it became the nation's dominant political worldview for a generation. The term itself was in active use by the 1830s.[7]

Jacksonian Democrats

This era, called the Jacksonian Era or Second Party System by historians and political scientists, lasted roughly from Jackson's 1828 presidential election until the practice of slavery became the dominant issue with the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act in 1854 and the political repercussions of the American Civil War dramatically reshaped American politics. It emerged when the long-dominant Democratic-Republican Party became factionalized around the 1824 presidential election. Jackson's supporters began to form the modern Democratic Party. His political rivals John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay created the National Republican Party, which would afterward combine with other anti-Jackson political groups to form the Whig Party.

Broadly speaking, the era was characterized by a democratic spirit. It built upon Jackson's equal political policy, subsequent to ending what he termed a monopoly of government by elites. Even before the Jacksonian era began, suffrage had been extended to a majority of white male adult citizens, a result which the Jacksonians celebrated.[8] Jacksonian democracy also promoted the strength of the presidency and the executive branch at the expense of Congress, while also seeking to broaden the public's participation in government. The Jacksonians demanded elected, not appointed, judges and rewrote many state constitutions to reflect the new values. In national terms, they favored geographical expansionism, justifying it in terms of manifest destiny.

There was usually a consensus among both Democrats (Jacksonians) and the Whigs (anti-Jacksonians) that battles over slavery should be avoided.

Jackson's expansion of democracy was largely exclusively limited to White Americans, as well as voting rights in the nation were extended to adult white males only. There was also little to no change, and in many cases a reduction of the rights of non-white U.S citizens, during the extensive period of Jacksonian democracy, spanning from 1829 to 1860.[9]

Jacksonian Presidents[edit]

In addition to Jackson, his second Vice President and one of the key organizational leaders of the Jacksonian Democratic Party, Martin Van Buren, served as president. He helped shape modern presidential campaign organizations and methods.[42]

Van Buren was defeated in 1840 by Whig William Henry Harrison. Harrison died just 30 days into his term and his Vice President John Tyler quickly reached accommodation with the Jacksonians. Tyler was then succeeded by James K. Polk, a Jacksonian who won the election of 1844 with Jackson's endorsement.[43] Franklin Pierce had been a supporter of Jackson as well. James Buchanan served in Jackson's administration as Minister to Russia and as Polk's Secretary of State, but he did not pursue Jacksonian policies. Finally, Andrew Johnson, who had been a strong supporter of Jackson, became president following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, but by then Jacksonian democracy had been pushed off the stage of American politics.