Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as "Stalwarts"[5][6]) were a political faction within the Republican Party originating from the party's founding in 1854—some six years before the Civil War—until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction. They called themselves "Radicals" because of their goal of immediate, complete, and permanent eradication of slavery in the United States. The Radical faction also included, though, very strong currents of Nativism, anti-Catholicism, and in favor of the Prohibition of alcoholic beverages. These policy goals and the rhetoric in their favor often made it extremely difficult for the Republican Party as a whole to avoid alienating large numbers of American voters from Irish Catholic, German-, and other White ethnic backgrounds.

For other uses, see Radical Republicans (disambiguation).

Radical Republicans

The Radicals were opposed during the war by the Moderate Republicans (led by President Abraham Lincoln), and by the Democratic Party. Radicals led efforts after the war to establish civil rights for former slaves and fully implement emancipation. After unsuccessful measures in 1866 resulted in violence against former slaves in the former rebel states, Radicals pushed the Fourteenth Amendment for statutory protections through Congress. They opposed allowing ex-Confederate politicians and military veterans to retake political power in the Southern U.S., and emphasized equality, civil rights and voting rights for the "freedmen", i.e., former slaves who had been freed during or after the Civil War by the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment.[7]

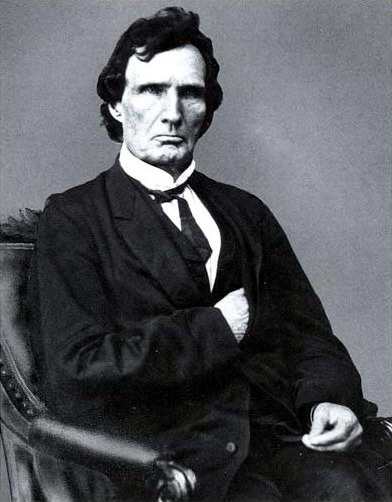

During the war, Radicals opposed Lincoln's initial selection of General George B. McClellan for top command of the major eastern Army of the Potomac and Lincoln's efforts in 1864 to bring seceded Southern states back into the Union as quickly and easily as possible. Lincoln later recognized McClellan as unfit and relieved him of his command. The Radicals tried passing their own Reconstruction plan through Congress in 1864. Lincoln vetoed it, as he was putting his own policy in effect through his power as military commander-in-chief. Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865.[8] Radicals demanded for the uncompensated abolition of slavery, while Lincoln wished instead to partially emulate the British Empire's abolition of slavery by financially compensating former slave owners who had remained loyal to the Union. The Radicals, led by Thaddeus Stevens, bitterly fought Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson. After Johnson vetoed various congressional acts favoring citizenship for freedmen and other bills he considered unconstitutional, the Radicals attempted to remove him from office through impeachment, which failed by one vote in 1868.

End of Reconstruction[edit]

By 1872, the Radicals were increasingly splintered and in the congressional elections of 1874, the Democrats took control of Congress. Many former Radicals joined the "Stalwart" faction of the Republican Party while many opponents joined the "Half-Breeds", who differed primarily on matters of patronage rather than policy.[24]

In state after state in the South, the so-called Redeemers' movement seized control from the Republicans until in 1876 only three Republican states were left: South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana. In the intensely disputed 1876 U.S. presidential election, Republican presidential candidate Rutherford B. Hayes was declared the winner following the Compromise of 1877 (a corrupt bargain): he obtained the electoral votes of those states, and with them the presidency, by committing himself to removing federal troops from those states. Deprived of military support, Reconstruction came to an end. "Redeemers" took over in these states as well. As white Democrats now dominated all Southern state legislatures, the period of Jim Crow laws began, and rights were progressively taken away from blacks. This period would last over 80 years, until the gains made by the Civil Rights Movement.