Regency era

The Regency era of British history is commonly described as the years between c. 1795 and 1837, although the official regency for which it is named only spanned the years 1811 to 1820. King George III first suffered debilitating illness in the late 1780s, and relapsed into his final mental illness in 1810; by the Regency Act 1811, his eldest son George, Prince of Wales, was appointed prince regent to discharge royal functions. When George III died in 1820, the Prince Regent succeeded him as George IV. In terms of periodisation, the longer timespan is roughly the final third of the Georgian era (1714–1837), encompassing the last 25 years or so of George III's reign, including the official Regency, and the complete reigns of both George IV and his brother and successor William IV. It ends with the accession of Queen Victoria in June 1837 and is followed by the Victorian era (1837–1901).

"The Regency" redirects here. For other uses, see Regency (disambiguation).

Although the Regency era is remembered as a time of refinement and culture, that was the preserve of the wealthy few, especially those in the Prince Regent's own social circle. For the masses, poverty was rampant as population began to concentrate due to industrial labour migration. City dwellers lived in increasingly larger slums, a state of affairs severely aggravated by the combined impact of war, economic collapse, mass unemployment, a bad harvest in 1816 (the "Year Without a Summer"), and an ongoing population boom. Political response to the crisis included the Corn Laws, the Peterloo Massacre, and the Representation of the People Act 1832. Led by William Wilberforce, there was increasing support for the abolitionist cause during the Regency era, culminating in passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807 and the Slavery Abolition Act 1833.

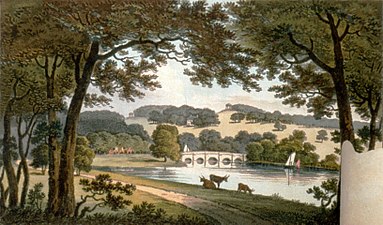

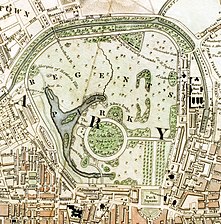

The longer timespan recognises the wider social and cultural aspects of the Regency era, characterised by the distinctive fashions, architecture and style of the period. The first 20 years to 1815 were overshadowed by the Napoleonic Wars. Throughout the whole period, the Industrial Revolution gathered pace and achieved significant progress by the coming of the railways and the growth of the factory system. The Regency era overlapped with Romanticism and many of the major artists, musicians, novelists and poets of the Romantic movement were prominent Regency figures, such as Jane Austen[2], William Blake, Lord Byron, John Constable, John Keats, John Nash, Ann Radcliffe, Walter Scott, Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, J. M. W. Turner and William Wordsworth.

Legislative background[edit]

George III (1738–1820) became King of Great Britain on 25 October 1760 when he was 22 years old, succeeding his grandfather George II. George III had himself been the subject of legislation to provide for a regency when Parliament passed the Minority of Successor to Crown Act 1751 following the death of his father Frederick, Prince of Wales, on 31 March 1751. George became heir apparent at the age of 12 and he would have succeeded as a minor if his grandfather had died before 4 June 1756, George's 18th birthday. As a contingency, the Act provided for his mother, Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales, to be appointed regent and discharge most but not all royal functions.[3]

In 1761, George III married Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and over the following years they had 15 children (nine sons and six daughters). The eldest was Prince George, born on 12 August 1762 as heir apparent. He was named Prince of Wales soon after his birth. By 1765, three infant children led the order of succession and Parliament again passed a Regency Act as contingency. The Minority of Heir to the Crown Act 1765 provided for either Queen Charlotte or Princess Augusta to act as regent if necessary.[3] George III had a long episode of mental illness in the summer of 1788. Parliament proposed the Regency Bill 1789 which was passed by the House of Commons. Before the House of Lords could debate it, the King recovered and the Bill was withdrawn. Had it been passed into law, the Prince of Wales would have become the regent in 1789.[4]

The King's mental health continued to be a matter of concern but, whenever he was of sound mind, he opposed any further moves to implement a Regency Act. Finally, following the death on 2 November 1810 of his youngest daughter, Princess Amelia, he became permanently insane. Parliament passed the Care of King During his Illness, etc. Act 1811, commonly known as the Regency Act 1811. The King was suspended from his duties as head of state and the Prince of Wales assumed office as Prince Regent on 5 February 1811.[5] At first, Parliament restricted some of the Regent's powers, but the constraints expired one year after the passage of the Act.[6] The Regency ended when George III died on 29 January 1820 and the Prince Regent succeeded him as George IV.[7]

After George IV died in 1830, a further Regency Act was passed by Parliament. George IV was succeeded by his brother William IV. His wife, Queen Adelaide, was 37 and there were no surviving legitimate children. The heir presumptive was Princess Victoria of Kent, aged eleven. The new Act provided for her mother, Victoria, Dowager Duchess of Kent to become regent in the event of William's death before 24 May 1837, the young Victoria's 18th birthday. The Act made allowance for Adelaide having another child, either before or after William's death. If the latter scenario had arisen, Victoria would have become Queen only temporarily until the new monarch was born. Adelaide had no more children and, as it happened, William died on 20 June 1837, just four weeks after Victoria was 18.[8]

Perceptions[edit]

Periodisation terminology[edit]

Officially, the Regency began on 5 February 1811 and ended on 29 January 1820 but the "Regency era", as such, is generally perceived to have been much longer. The term is commonly, though loosely, applied to the period from c. 1795 until the accession of Queen Victoria on 20 June 1837.[9] The Regency Era is a sub-period of the longer Georgian era (1714–1837), both of which were followed by the Victorian era (1837–1901). The latter term had contemporaneous usage although some historians give it an earlier startpoint, typically the enactment of the Great Reform Act on 7 June 1832.[10][11][12]

Social, economic and political counterpoints[edit]

The Prince Regent himself was one of the leading patrons of the arts and architecture. He ordered the costly building and refurbishing of the exotic Brighton Pavilion, the ornate Carlton House, and many other public works and architecture. This all required considerable expense which neither the Regent himself nor HM Treasury could afford. The Regent's extravagance was pursued at the expense of the common people.[13]

While the Regency is noted for its elegance and achievements in the fine arts and architecture, there was a concurrent need for social, political and economic change. The country was enveloped in the Napoleonic Wars until June 1815 and the conflict heavily impacted commerce at home and internationally. There was mass unemployment and, in 1816, an exceptionally bad harvest. In addition, the country underwent a population boom and the combination of these factors resulted in rampant poverty. Apart from the national unity government led by William Grenville from February 1806 to March 1807, all governments from December 1783 to November 1830 were formed and led by Tories. Their responses to the national crisis included the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 and the various Corn Laws. The Whig government of Earl Grey passed the Great Reform Act in 1832.[12][14]

Essentially, England during the Regency era was a stratified society in which political power and influence lay in the hands of the landed class. Their fashionable locales were worlds apart from the slums in which the majority of people existed. The slum districts were known as rookeries, a notorious example being St Giles in London. These were places where alcoholism, gambling, prostitution, thievery and violence prevailed.[15] The population boom, comprising an increase from just under a million in 1801 to one and a quarter million by 1820, heightened the crisis.[15] Robert Southey drew a comparison between the squalor of the slums and the glamour of the Regent's circle:[16]

Among the popular newspapers, pamphlets and other publications of the era were:

Science and technology[edit]

In 1814, The Times adopted steam printing. Using this method, it could print 1,100 sheets every hour, five and a half times the prior rate of 200 per hour.[26] The faster speed of printing enabled the rise of the "silver fork novels" which depicted the lives of the rich and aristocratic. Publishers used these as a way of spreading gossip and scandal, often clearly hinting at identities. The novels were popular during the later years of the Regency era.[27]

Sport and recreation[edit]

Women's activities[edit]

During the Regency era and well into the succeeding Victorian era, society women were discouraged from exertion although many did take the opportunity to pursue activities such as dancing, riding and walking that were recreational rather than competitive. Depending on a lady's rank, she may be expected to be proficient in reading and writing, mathematics, dancing, music, sewing, and embroidery[28].[29] In Pride and Prejudice, the Bennet sisters are frequently out walking and it is at a ball where Elizabeth meets Mr Darcy. There was a contemporary belief that people had limited energy levels with women, as the "weaker sex", being most at risk of over-exertion because their menstruation cycles caused periodic energy reductions.[30]

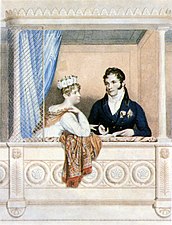

Balls[edit]

One of the most common activities among the upper class was attending and hosting balls, house parties, and more. These often included dancing, food, and gossip. The food generally served included items such as white soup made with veal stock, almonds and cream, cold meats, salads, etc.[31]