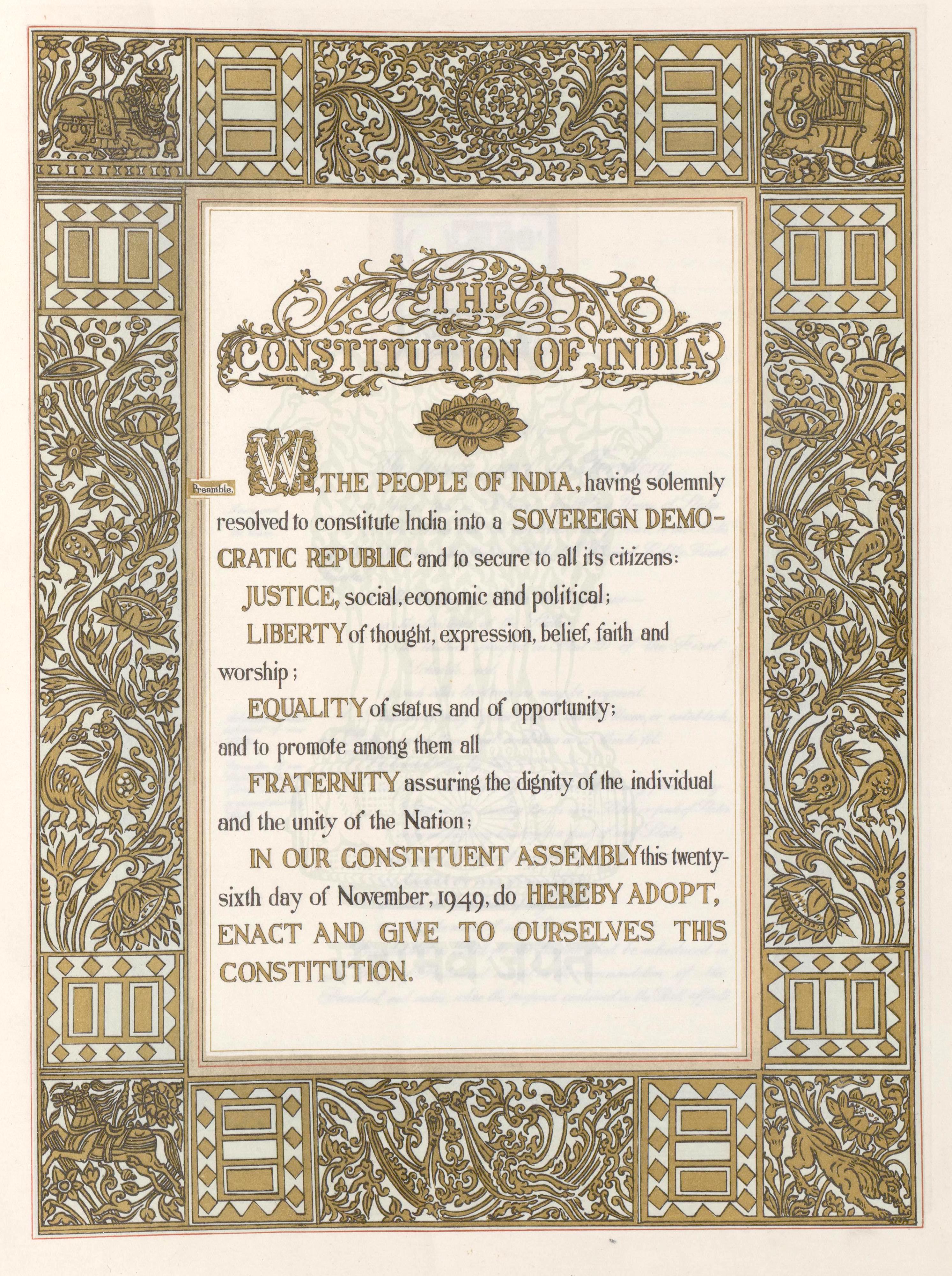

Constitution of India

The Constitution of India is the supreme law of India.[2][3] The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures, powers, and duties of government institutions and sets out fundamental rights, directive principles, and the duties of citizens, based on the proposal suggested by M. N. Roy. It is the longest written national constitution in the world.[4][5][6]

Constitution of India

26 November 1949

26 January 1950

Three (Executive, Legislature and Judiciary)

Two (Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha)

Prime Minister of India–led cabinet responsible to the lower house of the parliament

Federal[1]

Yes, for presidential and vice presidential elections

2

Constitution of India (PDF), 9 September 2020, archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2020

284 members of the Constituent Assembly

It imparts constitutional supremacy (not parliamentary supremacy, since it was created by a constituent assembly rather than Parliament) and was adopted by its people with a declaration in its preamble. Parliament cannot override the constitution.[7]

It was adopted by the Constituent Assembly of India on 26 November 1949 and became effective on 26 January 1950.[8] The constitution replaced the Government of India Act 1935 as the country's fundamental governing document, and the Dominion of India became the Republic of India. To ensure constitutional autochthony, its framers repealed prior acts of the British parliament in Article 395.[9] India celebrates its constitution on 26 January as Republic Day.[10]

The constitution declares India a sovereign, socialist, secular,[11] and democratic republic, assures its citizens justice, equality, and liberty, and endeavours to promote fraternity.[12] The original 1950 constitution is preserved in a nitrogen-filled case at the Parliament House in New Delhi.[13]

International law

The Constitution includes treaty making as part of the executive power given to the President.[117] Because the President must act in accordance with the advice of the Council of Ministers, the Prime Minister is the chief party responsible for making international treaties in the Constitution. Because the legislative power rests with Parliament, the President's signature on an international agreement does not bring it into effect domestically or enable courts to enforce its provisions. Article 253 of the Constitution bestows this power on Parliament, enabling it to make laws necessary for implementing international agreements and treaties.[118] These provisions indicate that the Constitution of India is dualist, that is, treaty law only takes effect when a domestic law passed using the normal processes incorporates it into domestic law.[119]

Recent Supreme Court decisions have begun to change this convention, incorporating aspects of international law without enabling legislation from parliament.[120] For example, in Gramophone Company of India Ltd. v Birendra Bahadur Pandey, the Court held that "the rules of international law are incorporated into national law and considered to be part of the national law, unless they are in conflict with an Act of Parliament."[121] In essence, this implies that international law applies domestically unless parliament says it does not.[119] This decision moves the Indian Constitution to a more hybrid regime, but not to a fully monist one.

According to Granville Austin, "The Indian constitution is first and foremost a social document, and is aided by its Parts III & IV (Fundamental Rights & Directive Principles of State Policy, respectively) acting together, as its chief instruments and its conscience, in realising the goals set by it for all the people."[h][122] The constitution has deliberately been worded in generalities (not in vague terms) to ensure its flexibility.[123] John Marshall, the fourth chief justice of the United States, said that a constitution's "great outlines should be marked, its important objects designated, and the minor ingredients which compose those objects be deduced from the nature of the objects themselves."[124] A document "intended to endure for ages to come",[125] it must be interpreted not only based on the intention and understanding of its framers, but in the existing social and political context.

The "right to life" guaranteed under Article 21[A] has been expanded to include a number of human rights, including:[4]

At the conclusion of his book, Making of India's Constitution, retired Supreme Court Justice Hans Raj Khanna wrote: