Electroencephalography

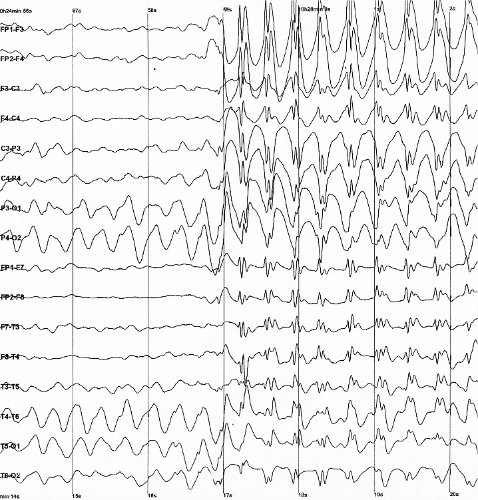

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a method to record an electrogram of the spontaneous electrical activity of the brain. The biosignals detected by EEG have been shown to represent the postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex and allocortex.[1] It is typically non-invasive, with the EEG electrodes placed along the scalp (commonly called "scalp EEG") using the International 10–20 system, or variations of it. Electrocorticography, involving surgical placement of electrodes, is sometimes called "intracranial EEG". Clinical interpretation of EEG recordings is most often performed by visual inspection of the tracing or quantitative EEG analysis.

Not to be confused with other types of electrography.

Voltage fluctuations measured by the EEG bioamplifier and electrodes allow the evaluation of normal brain activity. As the electrical activity monitored by EEG originates in neurons in the underlying brain tissue, the recordings made by the electrodes on the surface of the scalp vary in accordance with their orientation and distance to the source of the activity. Furthermore, the value recorded is distorted by intermediary tissues and bones, which act in a manner akin to resistors and capacitors in an electrical circuit. This means not all neurons will contribute equally to an EEG signal, with an EEG predominately reflecting the activity of cortical neurons near the electrodes on the scalp. Deep structures within the brain further away from the electrodes will not contribute directly to an EEG; these include the base of the cortical gyrus, mesial walls of the major lobes, hippocampus, thalamus, and brain stem.[2]

A healthy human EEG will show certain patterns of activity that correlate with how awake a person is. The range of frequencies one observes are between 1 and 30 Hz, and amplitudes will vary between 20 and 100 μV. The observed frequencies are subdivided into various groups: alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), delta (0.5–4 Hz), and theta (4–7 Hz). Alpha waves are observed when a person is in a state of relaxed wakefulness and are mostly prominent over the parietal and occipital sites. During intense mental activity, beta waves are more prominent in frontal areas as well as other regions. If a relaxed person is told to open their eyes, one observes alpha activity decreasing and an increase in beta activity. Theta and delta waves are not seen in wakefulness, and if they are, it is a sign of brain dysfunction.[2]

EEG can detect abnormal electrical discharges such as sharp waves, spikes, or spike-and-wave complexes that are seen in people with epilepsy; thus, it is often used to inform the medical diagnosis. EEG can detect the onset and spatio-temporal (location and time) evolution of seizures and the presence of status epilepticus. It is also used to help diagnose sleep disorders, depth of anesthesia, coma, encephalopathies, cerebral hypoxia after cardiac arrest, and brain death. EEG used to be a first-line method of diagnosis for tumors, stroke, and other focal brain disorders,[3][4] but this use has decreased with the advent of high-resolution anatomical imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). Despite its limited spatial resolution, EEG continues to be a valuable tool for research and diagnosis. It is one of the few mobile techniques available and offers millisecond-range temporal resolution, which is not possible with CT, PET, or MRI.[5][6]

Derivatives of the EEG technique include evoked potentials (EP), which involves averaging the EEG activity time-locked to the presentation of a stimulus of some sort (visual, somatosensory, or auditory). Event-related potentials (ERPs) refer to averaged EEG responses that are time-locked to more complex processing of stimuli; this technique is used in cognitive science, cognitive psychology, and psychophysiological research.

Mechanisms[edit]

The brain's electrical charge is maintained by billions of neurons.[49] Neurons are electrically charged (or "polarized") by membrane transport proteins that pump ions across their membranes. Neurons are constantly exchanging ions with the extracellular milieu, for example to maintain resting potential and to propagate action potentials. Ions of similar charge repel each other, and when many ions are pushed out of many neurons at the same time, they can push their neighbours, who push their neighbours, and so on, in a wave. This process is known as volume conduction. When the wave of ions reaches the electrodes on the scalp, they can push or pull electrons on the metal in the electrodes. Since metal conducts the push and pull of electrons easily, the difference in push or pull voltages between any two electrodes can be measured by a voltmeter. Recording these voltages over time gives us the EEG.[50]

The electric potential generated by an individual neuron is far too small to be picked up by EEG or MEG.[51] EEG activity therefore always reflects the summation of the synchronous activity of thousands or millions of neurons that have similar spatial orientation. If the cells do not have similar spatial orientation, their ions do not line up and create waves to be detected. Pyramidal neurons of the cortex are thought to produce the most EEG signal because they are well-aligned and fire together. Because voltage field gradients fall off with the square of distance, activity from deep sources is more difficult to detect than currents near the skull.[52]

Scalp EEG activity shows oscillations at a variety of frequencies. Several of these oscillations have characteristic frequency ranges, spatial distributions and are associated with different states of brain functioning (e.g., waking and the various sleep stages). These oscillations represent synchronized activity over a network of neurons. The neuronal networks underlying some of these oscillations are understood (e.g., the thalamocortical resonance underlying sleep spindles), while many others are not (e.g., the system that generates the posterior basic rhythm). Research that measures both EEG and neuron spiking finds the relationship between the two is complex, with a combination of EEG power in the gamma band and phase in the delta band relating most strongly to neuron spike activity.[53]

Inexpensive EEG devices exist for the low-cost research and consumer markets. Recently, a few companies have miniaturized medical grade EEG technology to create versions accessible to the general public. Some of these companies have built commercial EEG devices retailing for less than US$100.