Poetry

Poetry (a term derived from the Greek word poiesis, "making"), also called verse,[note 1] is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic[1][2][3] qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, a prosaic ostensible meaning. A poem is a literary composition, written by a poet, using this principle.

This article is about the art form. For other uses, see Poetry (disambiguation).

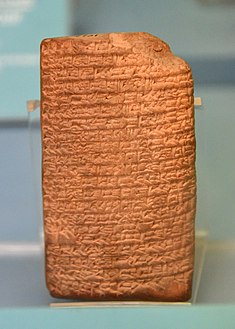

Poetry has a long and varied history, evolving differentially across the globe. It dates back at least to prehistoric times with hunting poetry in Africa and to panegyric and elegiac court poetry of the empires of the Nile, Niger, and Volta River valleys.[4] Some of the earliest written poetry in Africa occurs among the Pyramid Texts written during the 25th century BCE. The earliest surviving Western Asian epic poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh, was written in the Sumerian language.

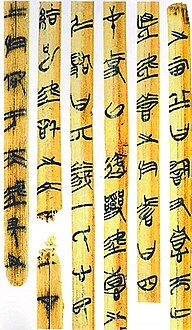

Early poems in the Eurasian continent evolved from folk songs such as the Chinese Shijing as well as from religious hymns (the Sanskrit Rigveda, the Zoroastrian Gathas, the Hurrian songs, and the Hebrew Psalms); or from a need to retell oral epics, as with the Egyptian Story of Sinuhe, Indian epic poetry, and the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Ancient Greek attempts to define poetry, such as Aristotle's Poetics, focused on the uses of speech in rhetoric, drama, song, and comedy. Later attempts concentrated on features such as repetition, verse form, and rhyme, and emphasized the aesthetics which distinguish poetry from more objectively-informative prosaic writing.

Poetry uses forms and conventions to suggest differential interpretations of words, or to evoke emotive responses. Devices such as assonance, alliteration, onomatopoeia, and rhythm may convey musical or incantatory effects. The use of ambiguity, symbolism, irony, and other stylistic elements of poetic diction often leaves a poem open to multiple interpretations. Similarly, figures of speech such as metaphor, simile, and metonymy[5] establish a resonance between otherwise disparate images—a layering of meanings, forming connections previously not perceived. Kindred forms of resonance may exist, between individual verses, in their patterns of rhyme or rhythm.

Some poetry types are unique to particular cultures and genres and respond to characteristics of the language in which the poet writes. Readers accustomed to identifying poetry with Dante, Goethe, Mickiewicz, or Rumi may think of it as written in lines based on rhyme and regular meter. There are, however, traditions, such as Biblical poetry and alliterative verse, that use other means to create rhythm and euphony. Much modern poetry reflects a critique of poetic tradition,[6] testing the principle of euphony itself or altogether forgoing rhyme or set rhythm.[7][8]

Poets – as, from the Greek, "makers" of language – have contributed to the evolution of the linguistic, expressive, and utilitarian qualities of their languages. In an increasingly globalized world, poets often adapt forms, styles, and techniques from diverse cultures and languages.

A Western cultural tradition (extending at least from Homer to Rilke) associates the production of poetry with inspiration – often by a Muse (either classical or contemporary), or through other (often canonised) poets' work which sets some kind of example or challenge.

In first-person poems, the lyrics are spoken by an "I", a character who may be termed the speaker, distinct from the poet (the author). Thus if, for example, a poem asserts, "I killed my enemy in Reno", it is the speaker, not the poet, who is the killer (unless this "confession" is a form of metaphor which needs to be considered in closer context – via close reading).