Messiah in Judaism

The Messiah in Judaism (Hebrew: מָשִׁיחַ, romanized: māšīaḥ) is a savior and liberator figure in Jewish eschatology who is believed to be the future redeemer of the Jews. The concept of messianism originated in Judaism,[1][2] and in the Hebrew Bible a messiah is a king or High Priest of Israel traditionally anointed with holy anointing oil.[3] However, messiahs were not exclusively Jewish, as the Hebrew Bible refers to Cyrus the Great, Achaemenid Emperor, as a messiah[4][5][6][7] for his decree to rebuild the Jerusalem Temple.

"Jewish Messiah" and "Mashiach" redirect here. See also Mashiach (disambiguation) and List of Jewish messiah claimants. For the Christian religious movement, see Messianic Judaism.

In Jewish eschatology, the Messiah is a future Jewish king from the Davidic line, who is expected to be anointed with holy anointing oil and rule the Jewish people during the Messianic Age and world to come.[1][2][8] The Messiah is often referred to as "King Messiah" (Hebrew: מלך משיח, romanized: melekh mashiach) or malka meshiḥa in Aramaic.[9]

Jewish messianism gave birth to Christianity, which started as a Second Temple period messianic Jewish sect or religious movement.[10][11]

Etymology[edit]

In Jewish eschatology, the term mashiach, or "Messiah", refers specifically to a future Jewish king from the Davidic line, who is expected to save the Jewish nation, and will be anointed with holy anointing oil and rule the Jewish people during the Messianic Age.[1][2][8][12] The Messiah is often referred to as "King Messiah", or, in Hebrew, מלך משיח (melekh mashiach), and, in Aramaic, malka meshiḥa.[9] In a generalized sense, messiah has "the connotation of a savior or redeemer who would appear at the end of days and usher in the kingdom of God, the restoration of Israel, or whatever dispensation was considered to be the ideal state of the world."[12]

Messianism "denotes a movement, or a system of beliefs and ideas, centered on the expectation of the advent of a messiah."[12] Orthodox views hold that the Messiah will be descended from his father through the line of King David,[13] and will gather the Jews back into the Land of Israel, usher in an era of peace, build the Third Temple, father a male heir, re-institute the Sanhedrin, and so on. The word, mashiach, however, is rarely used in Jewish literature in the period from the 1st century BCE to the 1st century CE.[14]

Jewish tradition of the late, or early post-Second Temple period alludes to two redeemers, one suffering and the second fulfilling the traditional messianic role, namely Mashiach ben Yosef, and Mashiach ben David.[15][16][17][18][1][2] In general, the term "Messiah" unqualified refers to "Mashiach ben David" (Messiah, son of David).[1][2]

Belief in the future advent of the Messiah was first recorded in the Talmud[19] and later codified in halacha by Maimonides in Mishneh Torah as one of the fundamental requisites of the Jewish faith, concerning which has written: "Anyone who does not believe in him, or who does not wait for his arrival, has not merely denied the other prophets, but has also denied the Torah and Moses, our Rabbi."[20]

Post-Temple and medieval views[edit]

Talmud[edit]

The Talmud extensively discusses the coming of the Messiah (Sanhedrin 98a–99a, et al.) and describes a period of freedom and peace, which will be the time of ultimate goodness for the Jews. Tractate Sanhedrin contains a long discussion of the events leading to the coming of the Messiah.[note 4] The Talmud tells many stories about the Messiah, some of which represent famous Talmudic rabbis as receiving personal visitations from Elijah the Prophet and the Messiah.[note 5]

Midrash[edit]

There are innumerable references to the Messiah in Midrashic literature, where they often stretch the meaning of biblical verses. One such reference is found in the Midrash HaGadol (on Genesis 36:39) where Abba bar Kahana says: "What is meant by, 'In that day the root of Jesse, who shall stand as an ensign for the peoples, of him shall the nations inquire, and his rest shall be glorious' (Isaiah 11:10)? It means that when the banner of the anointed king shall be lifted-up, all the masts of ships belonging to the nations of the world shall be broken, while all the lines (halyard, downhaul and sheets) are cut loose, while all ships are broken asunder, and none of them remain excepting the banner of the son of David, as it says: 'who shall stand as an ensign for the peoples'. Likewise, when the banner of the son of David shall arise, all the languages belonging to the nations shall be made useless, and their customs shall be rendered null and void. The nations, at that time, will learn from the Messiah, as it says: 'of him shall the nations inquire' (ibid.); 'and his rest shall be glorious', meaning, he gives to them satisfaction, and tranquility, and they dwell in peace and quiet."[47]

Maimonides[edit]

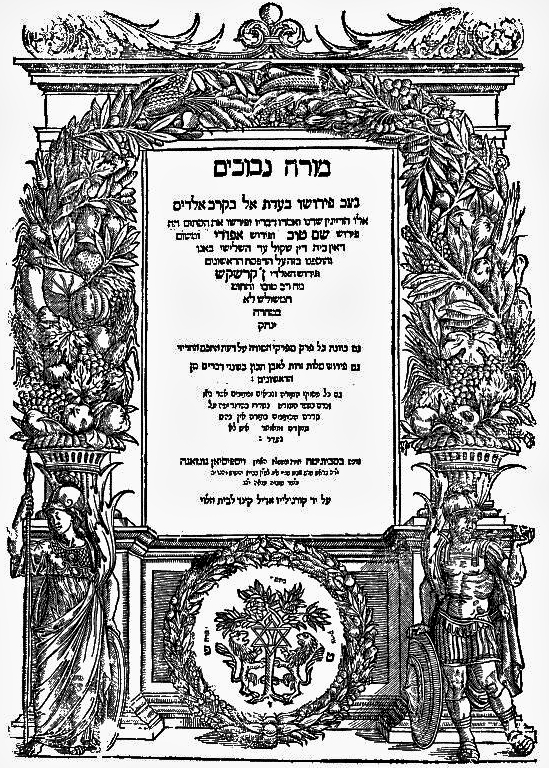

The influential Jewish philosopher Maimonides discussed the messiah in his Mishneh Torah, his 14-volume compendium of Jewish law, in the section Hilkhot Melakhim Umilchamoteihem, chapters 11 & 12.[note 6] According to Maimonides, Jesus of Nazareth is not the Messiah, as is claimed by Christians.[note 7]

Spanish Inquisition[edit]

Following the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, many Spanish rabbis such as Abraham ben Eliezer Halevi believed that the year 1524 would be the beginning of the Messianic Age and that the Messiah himself would appear in 1530–1531.[48]

Kabbalah and the Zohar[edit]

"…[This] tells you that all those involved with the Torah will not see punishment, neither in this world, in the times of Moshiach, nor in the World to Come"

How is it possible that in the times of Moshiach there can be punishments? They are the pangs for the birth of Mashiach: days will come... of serious punishments because the Zohar admits, like the Pentateuch in Deuteronomy, a terrible era before the era of maximum goodness and "double good" identified in the length of days of the World to Come. The Moshiach will conclude those days before and after with the pangs of the Moshiach to be projected into the "awakening" of the messianic time in its fullness, i.e. the World to Come; it is true for the Zohar that the Torah will testify favorably for Israel that thus he will not suffer the earthly judgment, not the judgment of Gehinnom and the angel of Death will not be able to harm him in any way.

"Length of days" refers to the definitive Tikkun in fact it refers to "the future World of Moshiach"; the warning that "days will come..." concerns those days that "Moshiach himself will bring to an end". Finally, "the awakening" occurs without excessively suffering "the pangs of Moshiach".[49]

Contemporary Jewish views[edit]

Orthodox Judaism[edit]

Orthodox Judaism maintains the 13 Principles of Faith as formulated by Maimonides in his introduction to Chapter Helek of the Mishna Torah. Each principle starts with the words Ani Maamin (I believe). Number 12 is the main principle relating to Mashiach. Orthodox Jews strictly believe in a Messiah, life after death, and restoration of the Promised Land:[50][51]

Calculation of appearance[edit]

According to the Talmud,[60] the Midrash,[61] and the Zohar,[62] the "deadline" by which the Messiah must appear is 6000 years from creation (approximately the year 2240 in the Gregorian calendar, though calculations vary).[note 10] Elaborating on this theme are numerous early and late Jewish scholars, including the Ramban,[66] Isaac Abrabanel,[67] Abraham Ibn Ezra,[68] Rabbeinu Bachya,[69] the Vilna Gaon,[70] the Lubavitcher Rebbe,[71] the Ramchal,[72] Aryeh Kaplan,[73] and Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis.[74]