Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin philosophia naturalis) is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

This article is about the philosophical study of nature. For the current in 19th-century German idealism, see Naturphilosophie.

From the ancient world (at least since Aristotle) until the 19th century, natural philosophy was the common term for the study of physics (nature), a broad term that included botany, zoology, anthropology, and chemistry as well as what we now call physics. It was in the 19th century that the concept of science received its modern shape, with different subjects within science emerging, such as astronomy, biology, and physics. Institutions and communities devoted to science were founded.[1] Isaac Newton's book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687) (English: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy) reflects the use of the term natural philosophy in the 17th century. Even in the 19th century, the work that helped define much of modern physics bore the title Treatise on Natural Philosophy (1867).

In the German tradition, Naturphilosophie (philosophy of nature) persisted into the 18th and 19th centuries as an attempt to achieve a speculative unity of nature and spirit, after rejecting the scholastic tradition and replacing Aristotelian metaphysics, along with those of the dogmatic churchmen, with Kantian rationalism. Some of the greatest names in German philosophy are associated with this movement, including Goethe, Hegel, and Schelling. Naturphilosophie was associated with Romanticism and a view that regarded the natural world as a kind of giant organism, as opposed to the philosophical approach of figures such as John Locke and others espousing a more mechanical philosophy of the world, regarding it as being like a machine.

Origin and evolution of the term[edit]

The term natural philosophy preceded current usage of natural science (i.e. empirical science). Empirical science historically developed out of philosophy or, more specifically, natural philosophy. Natural philosophy was distinguished from the other precursor of modern science, natural history, in that natural philosophy involved reasoning and explanations about nature (and after Galileo, quantitative reasoning), whereas natural history was essentially qualitative and descriptive.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, natural philosophy was one of many branches of philosophy, but was not a specialized field of study. The first person appointed as a specialist in Natural Philosophy per se was Jacopo Zabarella, at the University of Padua in 1577.

Modern meanings of the terms science and scientists date only to the 19th century. Before that, science was a synonym for knowledge or study, in keeping with its Latin origin. The term gained its modern meaning when experimental science and the scientific method became a specialized branch of study apart from natural philosophy,[2] especially since William Whewell, a natural philosopher from the University of Cambridge, proposed the term "scientist" in 1834 to replace such terms as "cultivators of science" and "natural philosopher".[3]

From the mid-19th century, when it became increasingly unusual for scientists to contribute to both physics and chemistry, "natural philosophy" came to mean just physics, and the word is still used in that sense in degree titles at the University of Oxford and University of Aberdeen. In general, chairs of Natural Philosophy established long ago at the oldest universities are nowadays occupied mainly by physics professors. Isaac Newton's book Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687), whose title translates to "Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy", reflects the then-current use of the words "natural philosophy", akin to "systematic study of nature". Even in the 19th century, a treatise by Lord Kelvin and Peter Guthrie Tait, which helped define much of modern physics, was titled Treatise on Natural Philosophy (1867).

Greek philosophers defined it as the combination of beings living in the universe, ignoring things made by humans.[4] The other definition refers to human nature.[4]

Scope[edit]

Plato's earliest known dialogue, Charmides, distinguishes between science or bodies of knowledge that produce a physical result, and those that do not. Natural philosophy has been categorized as a theoretical rather than a practical branch of philosophy (like ethics). Sciences that guide arts and draw on the philosophical knowledge of nature may produce practical results, but these subsidiary sciences (e.g., architecture or medicine) go beyond natural philosophy.

The study of natural philosophy seeks to explore the cosmos by any means necessary to understand the universe. Some ideas presuppose that change is a reality. Although this may seem obvious, there have been some philosophers who have denied the concept of metamorphosis, such as Plato's predecessor Parmenides and later Greek philosopher Sextus Empiricus, and perhaps some Eastern philosophers. George Santayana, in his Scepticism and Animal Faith, attempted to show that the reality of change cannot be proven. If his reasoning is sound, it follows that to be a physicist, one must restrain one's skepticism enough to trust one's senses, or else rely on anti-realism.

René Descartes' metaphysical system of mind–body dualism describes two kinds of substance: matter and mind. According to this system, everything that is "matter" is deterministic and natural—and so belongs to natural philosophy—and everything that is "mind" is volitional and non-natural, and falls outside the domain of philosophy of nature.

Branches and subject matter[edit]

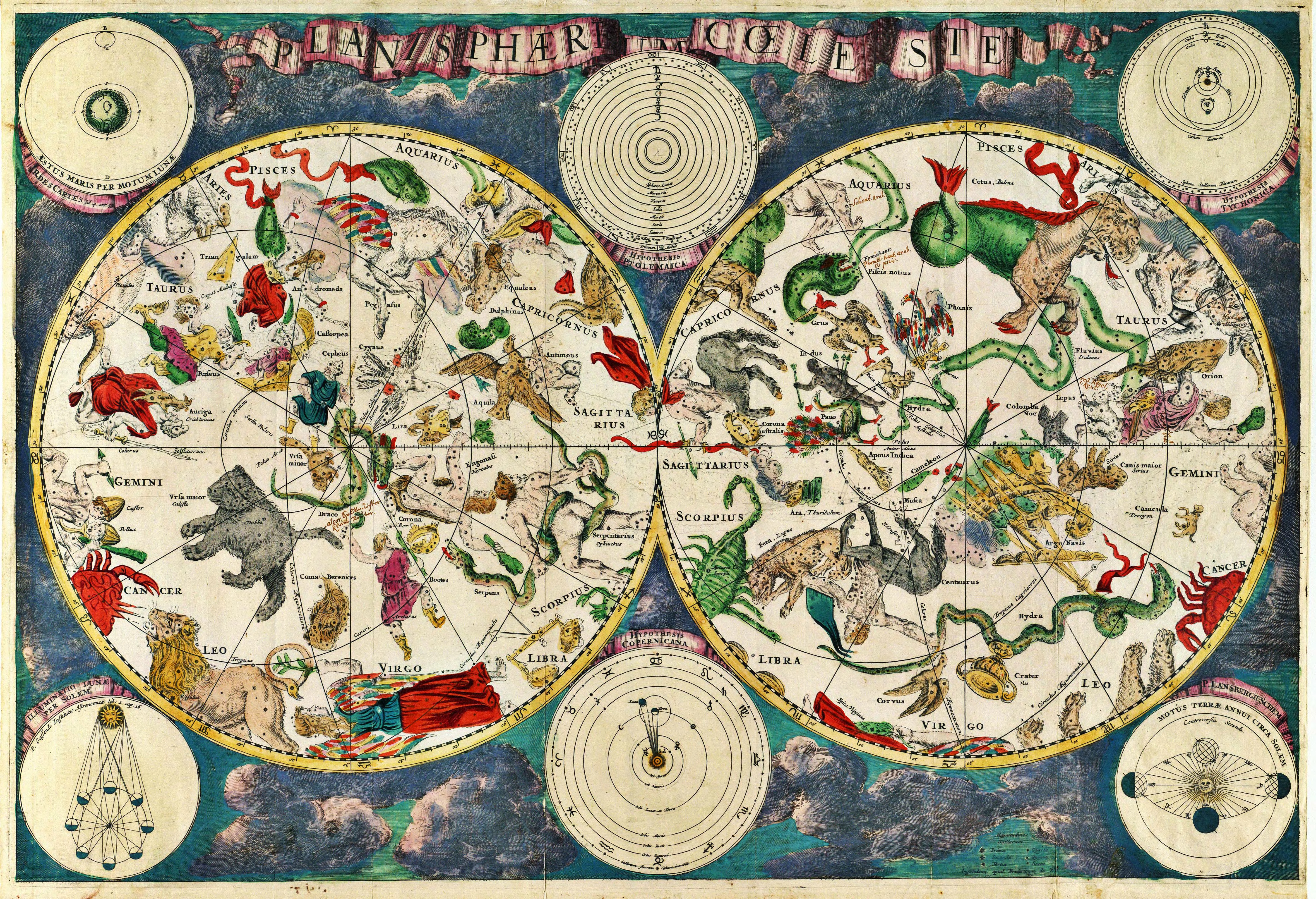

Major branches of natural philosophy include astronomy and cosmology, the study of nature on the grand scale; etiology, the study of (intrinsic and sometimes extrinsic) causes; the study of chance, probability and randomness; the study of elements; the study of the infinite and the unlimited (virtual or actual); the study of matter; mechanics, the study of translation of motion and change; the study of nature or the various sources of actions; the study of natural qualities; the study of physical quantities; the study of relations between physical entities; and the philosophy of space and time. (Adler, 1993)

Current work in the philosophy of science and nature[edit]

In the middle of the 20th century, Ernst Mayr's discussions on the teleology of nature brought up issues that were dealt with previously by Aristotle (regarding final cause) and Kant (regarding reflective judgment).[19]

Especially since the mid-20th-century European crisis, some thinkers argued the importance of looking at nature from a broad philosophical perspective, rather than what they considered a narrowly positivist approach relying implicitly on a hidden, unexamined philosophy.[20] One line of thought grows from the Aristotelian tradition, especially as developed by Thomas Aquinas. Another line springs from Edmund Husserl, especially as expressed in The Crisis of European Sciences. Students of his such as Jacob Klein and Hans Jonas more fully developed his themes. Last, but not least, there is the process philosophy inspired by Alfred North Whitehead's works.[21]

Among living scholars, Brian David Ellis, Nancy Cartwright, David Oderberg, and John Dupré are some of the more prominent thinkers who can arguably be classed as generally adopting a more open approach to the natural world. Ellis (2002) observes the rise of a "New Essentialism".[22] David Oderberg (2007) takes issue with other philosophers, including Ellis to a degree, who claim to be essentialists. He revives and defends the Thomistic-Aristotelian tradition from modern attempts to flatten nature to the limp subject of the experimental method. In Praise of Natural Philosophy: A Revolution for Thought and Life (2017), Nicholas Maxwell argues that we need to reform philosophy and put science and philosophy back together again to create a modern version of natural philosophy.