Political integration of India

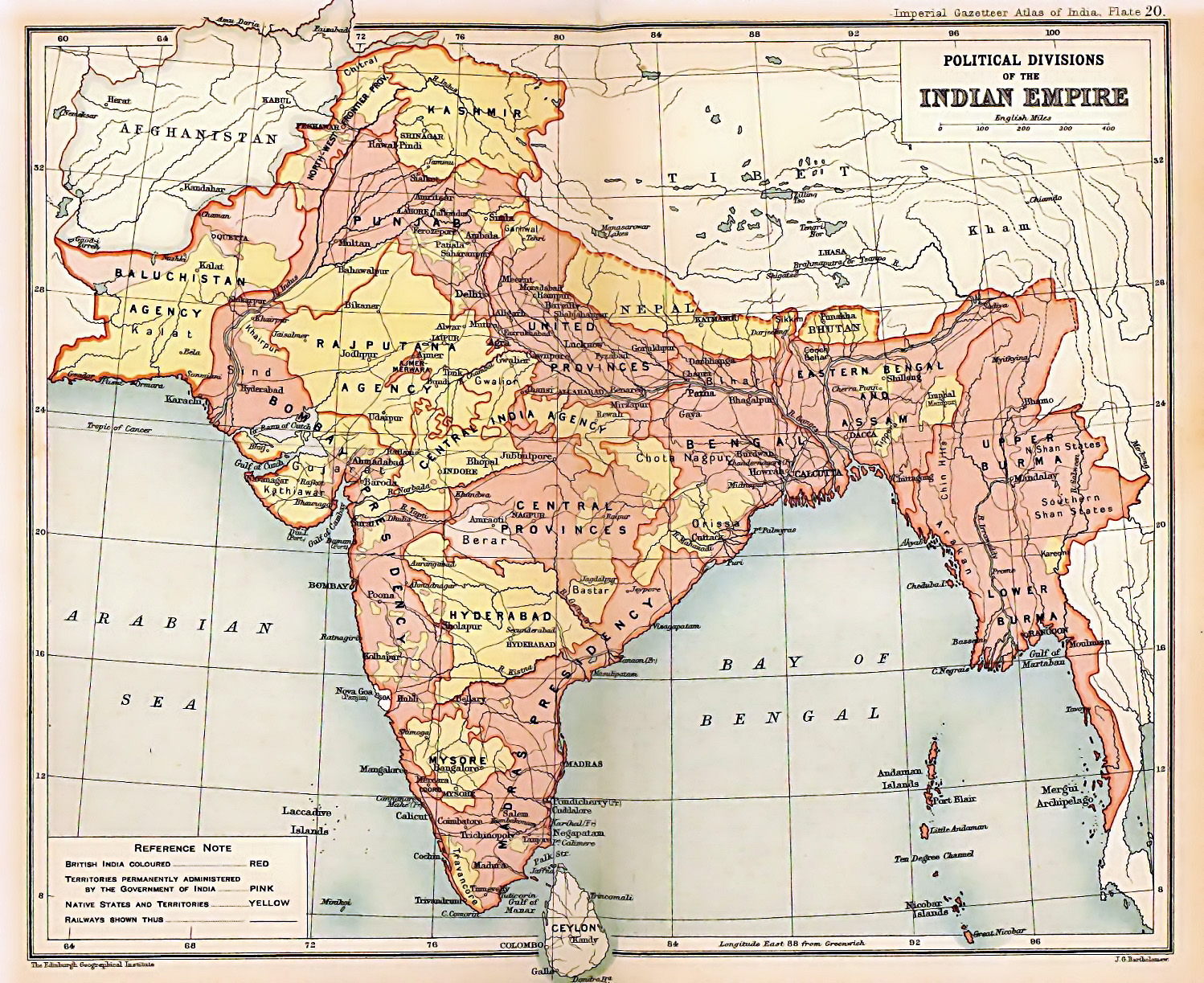

Before India gained independence in 1947, India (also called the Indian Empire) was divided into two sets of territories, one under direct British rule (British India), and the other consisting of princely states under the suzerainty of the British Crown, with control over their internal affairs remaining in the hands of their hereditary rulers. The latter included 562 princely states which had different types of revenue-sharing arrangements with the British, often depending on their size, population and local conditions. In addition, there were several colonial enclaves controlled by France and Portugal. After independence, the political integration of these territories into an Indian Union was a declared objective of the Indian National Congress, and the Government of India pursued this over the next decade.

In July 1946, Jawaharlal Nehru pointedly observed that no princely state could prevail militarily against the army of independent India.[1] In January 1947, Nehru said that independent India would not accept the divine right of kings.[2] In May 1947, he declared that any princely state which refused to join the Constituent Assembly would be treated as an enemy state.[3] Vallabhbhai Patel and V. P. Menon were more conciliatory towards the princes, and as the men charged with integrating the states, were successful in the task.[4] Through a combination of factors, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V. P. Menon coerced and coalesced the rulers of the various princely states to accede to India. Having secured their accession, they then proceeded, in a step-by-step process, to secure and extend the union government's authority over these states and transform their administrations until, by 1956, there was little difference between the territories that had been part of British India and those that had been princely states. Simultaneously, the Government of India, through a combination of military and diplomatic means, acquired de facto and de jure control over the remaining colonial enclaves, which too were integrated into India.

Although this process successfully integrated the vast majority of princely states into India, it was not as successful for a few, notably the former princely states of Jammu and Kashmir and Manipur, where active secessionist and separatist insurgencies continued to exist due to various reasons.

Princely states in India[edit]

The early history of British expansion in India was characterised by the co-existence of two approaches towards the existing princely states.[5] The first was a policy of annexation, where the British sought to forcibly absorb the Indian princely states into the provinces which constituted their Empire in India. The second was a policy of indirect rule, where the British assumed paramountcy over princely states, but conceded to them sovereignty and varying degrees of internal self-government.[6] During the early part of the 19th century, the policy of the British tended towards annexation, but the Indian Rebellion of 1857 forced a change in this approach, by demonstrating both the difficulty of absorbing and subduing annexed states, and the usefulness of princely states as a source of support.[7] In 1858, the policy of annexation was formally renounced, and British relations with the remaining princely states thereafter were based on subsidiary alliances, whereby the British exercised paramountcy over all princely states, with the British crown as ultimate suzerain, but at the same time respected and protected them as allies, taking control of their external relations.[8] The exact relations between the British and each princely state were regulated by individual treaties and varied widely, with some states having complete internal self-government, others being subject to significant control in their internal affairs, and some rulers being in effect little more than the owners of landed estates, with little autonomy.[9]

During the 20th century, the British made several attempts to integrate the princely states more closely with British India, in 1921 creating the Chamber of Princes as a consultative and advisory body,[10] and in 1936 transferring the responsibility for the supervision of smaller states from the provinces to the centre and creating direct relations between the Government of India and the larger princely states, superseding political agents.[11] A more ambitious aim was a scheme of federation contained in the Government of India Act 1935, which envisaged the princely states and British India being united under a federal government.[12] This scheme came close to success, but was abandoned in 1939 as a result of the outbreak of the Second World War.[13] As a result, in the 1940s the relationship between the princely states and the crown remained regulated by the principle of paramountcy and by the various treaties between the British crown and the states.[14]

Neither paramountcy nor the subsidiary alliances could continue after Indian independence. The British took the view that because they had been established directly between the British crown and the princely states, they could not be transferred to the newly independent dominions of India and Pakistan.[15] At the same time, the alliances imposed obligations on Britain that it was not prepared to continue to carry out, such as the obligation to maintain troops in India for the defence of the princely states. The British government therefore decided that paramountcy, together with all treaties between them and the princely states, would come to an end upon the British departure from India.[16]

Accepting integration[edit]

The princes' position[edit]

The rulers of the princely states were not uniformly enthusiastic about integrating their domains into independent India. The Jamkhandi State integrated first with Independent India. Some, such as the rulers of Bikaner and Jawhar, were motivated to join India out of ideological and patriotic considerations,[28] but others insisted that they had the right to join either India or Pakistan, to remain independent, or form a union of their own.[29] Bhopal, Travancore and Hyderabad announced that they did not intend to join either dominion.[30] Hyderabad went as far as to appoint trade representatives in European countries and commencing negotiations with the Portuguese to lease or buy Goa to give it access to the sea,[31] and Travancore pointed to the strategic importance to Western countries of its thorium reserves while asking for recognition.[32] Some states proposed a subcontinent-wide confederation of princely states, as a third entity in addition to India and Pakistan.[33] Bhopal attempted to build an alliance between the princely states and the Muslim League to counter the pressure being put on rulers by the Congress.[34]

A number of factors contributed to the collapse of this initial resistance and to nearly all non-Muslim majority princely states agreeing to accede to India. An important factor was the lack of unity among the princes. The smaller states did not trust the larger states to protect their interests, and many Hindu rulers did not trust Muslim princes, in particular Hamidullah Khan, the Nawab of Bhopal and a leading proponent of independence, whom they viewed as an agent for Pakistan.[35] Others, believing integration to be inevitable, sought to build bridges with the Congress, hoping thereby to gain a say in shaping the final settlement. The resultant inability to present a united front or agree on a common position significantly reduced their bargaining power in negotiations with the Congress.[36] The decision by the Muslim League to stay out of the Constituent Assembly was also fatal to the princes' plan to build an alliance with it to counter the Congress,[37] and attempts to boycott the Constituent Assembly altogether failed on 28 April 1947, when the states of Baroda, Bikaner, Cochin, Gwalior, Jaipur, Jodhpur, Patiala and Rewa took their seats in the Assembly.[38]

Many princes were also pressured by popular sentiment favouring integration with India, which meant their plans for independence had little support from their subjects.[39] The Maharaja of Travancore, for example, definitively abandoned his plans for independence after the attempted assassination of his dewan, Sir C. P. Ramaswami Iyer.[40] In a few states, the chief ministers or dewans played a significant role in convincing the princes to accede to India.[41] The key factors that led the states to accept integration into India were, however, the efforts of Lord Mountbatten, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and V. P. Menon. The latter two were respectively the political and administrative heads of the States Department, which was in charge of relations with the princely states.

Critical perspectives on the process of integration[edit]

The integration process repeatedly brought Indian and Pakistani leaders into conflict. During negotiations, Jinnah, representing the Muslim League, strongly supported the right of the princely states to remain independent, joining neither India nor Pakistan, an attitude which was diametrically opposed to the stance taken by Nehru and the Congress[151] and which was reflected in Pakistan's support of Hyderabad's bid to stay independent. Post-partition, the Government of Pakistan accused India of hypocrisy on the ground that there was little difference between the accession of the ruler of Junagadh to Pakistan—which India refused to recognise—and the accession of the Maharajah of Kashmir to India, and for several years refused to recognise the legality of India's incorporation of Junagadh, treating it as de jure Pakistani territory.[73]

Different theories have been proposed to explain the designs of Indian and Pakistani leaders in this period. Rajmohan Gandhi postulates that an ideal deal working in the mind of Patel was that if Muhammad Ali Jinnah let India have Junagadh and Hyderabad, Patel would not object to Kashmir acceding to Pakistan.[152] In his book Patel: A Life, Gandhi asserts that Jinnah sought to engage the questions of Junagadh and Hyderabad in the same battle. It is suggested that he wanted India to ask for a plebiscite in Junagadh and Hyderabad, knowing thus that the principle then would have to be applied to Kashmir, where the Muslim-majority would, he believed, vote for Pakistan. A speech by Patel at the Bahauddin College in Junagadh following the latter's take-over, where he said that "we would agree to Kashmir if they agreed to Hyderabad", suggests that he may have been amenable to this idea.[153] Although Patel's opinions were not India's policy, nor were they shared by Nehru, both leaders were angered at Jinnah's courting the princes of Jodhpur, Bhopal and Indore, leading them to take a harder stance on a possible deal with Pakistan.[154]

Modern historians have also re-examined the role of the States Department and Lord Mountbatten during the accession process. Ian Copland argues that the Congress leaders did not intend the settlement contained in the Instruments of Accession to be permanent even when they were signed, and at all times privately contemplated a complete integration of the sort that ensued between 1948 and 1950.[114] He points out that the mergers and cession of powers to the Government of India between 1948 and 1950 contravened the terms of the Instruments of Accession, and were incompatible with the express assurances of internal autonomy and preservation of the princely states which Mountbatten had given the princes.[155] Menon in his memoirs stated that the changes to the initial terms of accession were in every instance freely consented to by the princes with no element of coercion. Copland disagrees, on the basis that foreign diplomats at the time believed that the princes had been given no choice but to sign, and that a few princes expressed their unhappiness with the arrangements.[156] He also criticises Mountbatten's role, saying that while he stayed within the letter of the law, he was at least under a moral obligation to do something for the princes when it became apparent that the Government of India was going to alter the terms on which accession took place, and that he should never have lent his support to the bargain given that it could not be guaranteed after independence.[157] Both Copland and Ramusack argue that, in the ultimate analysis, one of the reasons why the princes consented to the demise of their states was that they felt abandoned by the British, and saw themselves as having little other option.[158] Older historians such as Lumby, in contrast, take the view that the princely states could not have survived as independent entities after the transfer of power, and that their demise was inevitable. They therefore view successful integration of all princely states into India as a triumph for the Government of India and Lord Mountbatten, and as a tribute to the sagacity of the majority of princes, who jointly achieved in a few months what the Empire had attempted, unsuccessfully, to do for over a century—unite all of India under one rule.[159]