Sun Yat-sen

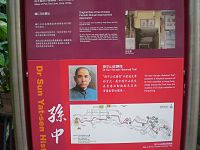

Sun Yat-sen[a] (traditional Chinese: 孫中山; simplified Chinese: 孙中山; pinyin: Sūn Zhōngshān, /ˈsʌn ˌjætˈsɛn/,[b] 12 November 1866 – 12 March 1925)[2][3][4] was a Chinese revolutionary statesman, physician, and political philosopher who served as the first provisional president of the Republic of China and the first leader of the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party of China). He is called the "Father of the Nation" in the present-day Republic of China (Taiwan) and the "Forerunner of the Revolution" in the People's Republic of China for his instrumental role in the overthrowing of the Qing dynasty during the 1911 Revolution. Sun is unique among 20th-century Chinese leaders for being widely revered by both the Communist Party in Mainland China and the Nationalist Party in Taiwan.[5]

"Sun Wen" redirects here. For the female footballer, see Sun Wen (footballer).

Sun Yat-sen

Office established

Office established

Zhang Renjie (as Chairman)

12 November 1866

Cuiheng Village, Hsiangshan County, Kwangtung Province, Qing Empire.

12 March 1925 (aged 58)

Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, Republic of China

- Chen Cuifen (concubine, 1892–1925)

- Haru Asada (concubine, 1897–1902)

4, including Sun Fo

- Sun Da-cheng (孫達成) (father)

- Madame Yang (mother)

Politician, writer, physician

1917–1925

孫中山

孙中山

Sūn Zhōngshān

Sūn Zhōngshān

ㄙㄨㄣ ㄓㄨㄥ ㄕㄢ

Sun Jongshan

Sun1 Chung1-shan1

Sun Jhong-shan

Syūn Jūng sāan

syun1 zung1 saan1

Sun Tiong-san

孫日新

孙日新

Sūn Rìxīn

Sūn Rìxīn

ㄙㄨㄣ ㄖˋ ㄒㄧㄣ

Sun Jihhshin

Sun1 Jih4-hsin1

Sun Rìh-sin

Syūn Yaht-sīn

syun1 jat6 san1

Suen Yat-sun

Sun E̍k-sin

孫逸仙

孙逸仙

Sūn Yìxiān

Sūn Yìxiān

ㄙㄨㄣ ㄧˋ ㄒㄧㄢ

Sun Yihshian

Sun1 Yi4-hsien1

Sun Yì-sian

Syūn Yaht-sīn

syun1 jat6 sin1

Suen Yat-sin

Sun E̍k-sian

孫文

孙文

Sūn Wén

Sūn Wén

ㄙㄨㄣ ㄨㄣˊ

Sun1 Wen2

Sun Wún

Syūn Màhn

syun1 man4

孫載之

孙载之

Sūn Zàizhī

Sūn Zàizhī

ㄙㄨㄣ ㄗㄞˋ ㄓ

Sun1 Tsai4-chih1

Sun Zài-jhih

Syūn Joi-jī

syun1 zoi3 zi1

孫德明

孙德明

Sūn Démíng

Sūn Démíng

ㄙㄨㄣ ㄉㄜˊ ㄇㄧㄥˊ

Sun1 Te2-ming2

Sun Dé-míng

Syūn Dāk-mìng

syun1 dak1 ming4

孫文

そんぶん

ソンブン

sonbun

sonbun

sonbun

Educated overseas, Sun is considered to be one of the greatest and most important leaders of modern China, but his political life was one of constant struggle and frequent exile. After the success of the revolution in 1911, he quickly resigned as president of the newly founded Republic of China and relinquished the position to Yuan Shikai. He soon went to exile in Japan for safety but returned to form and found a revolutionary government in Southern China, as a challenge to the warlords who controlled much of the nation. In 1923, he invited representatives of the Communist International to Canton (Guangzhou) to reorganize his party and formed a brittle alliance with the Chinese Communist Party. He did not live to see his party unify the country under his successor, Chiang Kai-shek, in the Northern Expedition. He died in Beijing of gallbladder cancer in 1925.[6]

Sun's chief legacy is his political philosophy known as the Three Principles of the People: Mínzú (民族主義; Mínzúzhǔyì) or nationalism (independence from foreign domination), Mínquán (民權主義; Mínquánzhǔyì) or "rights of the people" (also translated as "democracy"), and Mínshēng (民生主義; Mínshēngzhǔyì) or people's livelihood (sometimes translated as "communitarianism" or "welfarism").[7][8][9]

Early years[edit]

Birthplace and early life[edit]

Sun Te-ming was born on 12 November 1866 to Sun Dacheng and Madame Yang.[4] His birthplace was the village of Cuiheng, Xiangshan County (now Zhongshan City), Canton Province (now Guangdong).[4] He had a cultural background of Hakka[13][14] and Cantonese. His father owned very little land and worked as a tailor in Macau and as a journeyman and a porter.[15] After finishing primary education and meeting childhood friend Lu Haodong,[3] he moved to Honolulu in the Kingdom of Hawaii, where he lived a comfortable life of modest wealth supported by his elder brother Sun Mei.[16][17][18][19]

Education[edit]

At the age of 10, in Hawaii, Sun began his schooling.[3] He went to secondary school in Hawaii.[20] By age 13 in 1878, after receiving a few years of local schooling, Sun went to live with his elder brother, Sun Mei (孫眉) in Honolulu.[3] Sun Mei financed Sun Yat-sen's education and would later be a major contributor for the overthrow of the Manchus (Qing dynasty).[16][17][18][19]

During his stay in Honolulu, Sun Yat-sen went to ʻIolani School, where he studied English, British history, mathematics, science, and Christianity.[3] Although he was originally unable to speak English, Sun Yat-sen quickly picked up the language, received a prize for academic achievement from King David Kalākaua, and graduated in 1882.[21] He then attended Oahu College (now known as Punahou School) for one semester.[3][22] In 1883, he was sent home to China, as his brother was becoming worried that Sun was beginning to embrace Christianity.[3]

When he returned to China in 1883 at age 17, Sun met up with his childhood friend Lu Haodong again at Beijidian (北極殿), a temple in Cuiheng.[3] They saw many villagers worshipping the Beiji (literally North Pole) Emperor-God in the temple and were dissatisfied with their ancient folk healing methods.[3] Both of them broke the effigy, incurring the wrath of fellow villagers, and escaped to Hong Kong.[3][23][24] After arriving there in November 1883, he studied at the Diocesan Home and Orphanage on Eastern Street (now the Diocesan Boys' School),[25][26] and from 15 April 1884 to his graduation in 1886, he was at The Government Central School on Gough Street (now Queen's College).[27][28]

In 1886, Sun studied medicine at the Guangzhou Boji Hospital under the Christian missionary John G. Kerr.[3] According to his book "Kidnapped in London", Sun in 1887 heard of the opening of the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (the forerunner of the University of Hong Kong) and immediately decided to benefit from the "advantages it offered."[29] Ultimately, he earned the license of Christian practice as a medical doctor from there in 1892.[3][12] Notably, of his class of 12 students, Sun was one of only two who graduated.[30][31][32]

Religious views and Christian baptism[edit]

In the early 1880s, Sun Mei had sent his brother to ʻIolani School, which was under the supervision of the Church of Hawaii and directed by an Anglican prelate, Alfred Willis, with the language of instruction being English. At the school, the young Sun first came in contact with Christianity.

Sun was later baptized in Hong Kong (on 4 May 1884) by Rev. Charles Robert Hager[33][34][35] an American missionary of the Congregational Church of the United States (American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions) to his brother's disdain. The minister would also develop a friendship with Sun.[36][37] Sun attended To Tsai Church (道濟會堂), founded by the London Missionary Society in 1888,[38] while he studied medicine in Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese. Sun pictured a revolution as similar to the salvation mission of the Christian church. His conversion to Christianity was related to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement.[37]

From failed uprisings to revolution[edit]

Huizhou Uprising[edit]

On 22 October 1900, Sun ordered the launch of the Huizhou Uprising to attack Huizhou and provincial authorities in Guangdong.[59] That came five years after the failed Guangzhou Uprising. This time, Sun appealed to the triads for help.[60] The uprising was another failure. Miyazaki, who participated in the revolt with Sun, wrote an account of the revolutionary effort under the title "33-Year Dream" (三十三年之夢) in 1902.[61][62][63]

Getting support from Siamese Chinese[edit]

In 1903, Sun made a secret trip to Bangkok in which he sought funds for his cause in Southeast Asia. His loyal followers published newspapers, providing invaluable support to the dissemination of his revolutionary principles and ideals among Siamese Chinese in Siam. In Bangkok, Sun visited Yaowarat Road, in the city's Chinatown. On that street, Sun gave a speech claiming that Overseas Chinese were "the Mother of the Revolution." He also met the local Chinese merchant Seow Houtseng,[64] who sent financial support to him.

Sun's speech on Yaowarat Road was commemorated by the street later being named "Sun Yat Sen Street" or "Soi Sun Yat Sen" (Thai: ซอยซุนยัตเซ็น) in his honour.[65]

Getting support from American Chinese[edit]

According to Lee Yun-ping, chairman of the Chinese historical society, Sun needed a certificate to enter the United States since the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 would have otherwise blocked him.[66]

In March 1904, while residing in Kula, Maui, Sun Yat-sen obtained a Certificate of Hawaiian Birth, issued by the Territory of Hawaii, stating that "he was born in the Hawaiian Islands on the 24th day of November, A.D. 1870."[67][68] He renounced it after it served its purpose to circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act.[68] Official files of the United States show that Sun had United States nationality, moved to China with his family at age 4, and returned to Hawaii 10 years later.[69]

On 6 April 1904, on his first attempt to enter the United States, Sun Yat-sen landed in San Francisco. He was detained and faced with possible deportation.[66] Sun, represented by the law firm of Ralston & Siddons, based in Washington DC, filed an appeal with the Commissioner-General of Immigration on 26 April 1904. On 28 April 1904, the acting secretary of the Department of Commerce and Labor in a four-page decision contained in the case file, set aside the order of deportation and ordered the Commissioner of Immigration in San Francisco to "permit the said Sun Yat-sen to land." Sun was then freed to embark on his fundraising tour in the United States.[66]

In popular culture[edit]

Opera[edit]

Dr. Sun Yat-sen[171] (中山逸仙; ZhōngShān yì xiān) is a 2011 Chinese-language western-style opera in three acts by the New York-based American composer Huang Ruo, who was born in China and is a graduate of Oberlin College's Conservatory as well as the Juilliard School. The libretto was written by Candace Mui-ngam Chong, a recent collaborator with playwright David Henry Hwang.[172] It was performed in Hong Kong in October 2011 and was given its North America premiere on 26 July 2014 at the Santa Fe Opera.

Television series and films[edit]

Sun Yat-sen's life is portrayed in various films, mainly The Soong Sisters and Road to Dawn. A fictionalized assassination attempt on his life was featured in Bodyguards and Assassins. He is also portrayed during his struggle to overthrow the Qing dynasty in Once Upon a Time in China II. The television series Towards the Republic features Ma Shaohua as Sun. In 1911, a film commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Revolution, Winston Chao played Sun.[173] In Space: Above and Beyond, one of the starships of the China Navy is named the Sun Yat-sen.[174]