Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew (עִבְרִית מִקְרָאִית ⓘ or לְשׁוֹן הַמִּקְרָא ⓘ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite branch of Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Israel, roughly west of the Jordan River and east of the Mediterranean Sea. The term "Hebrew" (ivrit) was not used for the language in the Hebrew Bible, which was referred to as שְֹפַת כְּנַעַן (sefat kena'an, i.e. language of Canaan) or יְהוּדִית (Yehudit, i.e. Judaean), but the name was used in Ancient Greek and Mishnaic Hebrew texts.[1]

Biblical Hebrew

attested from the 10th century BCE; developed into Mishnaic Hebrew after the Jewish–Roman wars in the first century CE

Either:hbo – Ancient Hebrewsmp – Samaritan Hebrew

The Hebrew language is attested in inscriptions from about the 10th century BCE,[2][3] when it was almost identical to Phoenician and other Canaanite languages, and spoken Hebrew persisted through and beyond the Second Temple period, which ended in the siege of Jerusalem (70 CE). It eventually developed into Mishnaic Hebrew, spoken until the fifth century CE.

The language of the Hebrew Bible reflects various stages of the Hebrew language in its consonantal skeleton, as well as a vocalization system which was added in the Middle Ages by the Masoretes. There is also some evidence of regional dialectal variation, including differences between Biblical Hebrew as spoken in the northern Kingdom of Israel and in the southern Kingdom of Judah. The consonantal text was transmitted in manuscript form, and underwent redaction in the Second Temple period, but its earliest portions (parts of Amos, Isaiah, Hosea and Micah) can be dated to the late 8th to early 7th centuries BCE.

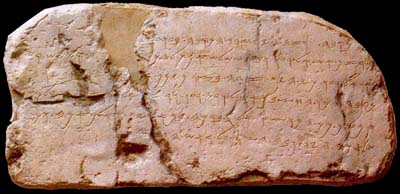

Biblical Hebrew has been written with a number of different writing systems. From around the 12th century BCE until the 6th century BCE the Hebrews used the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet. This was retained by the Samaritans, who use the descendent Samaritan script to this day. However, the Imperial Aramaic alphabet gradually displaced the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet after the exile to Babylon, and it became the source for the Modern Hebrew alphabet. All of these scripts were lacking letters to represent all of the sounds of Biblical Hebrew, although these sounds are reflected in Greek and Latin transcriptions/translations of the time. These scripts originally indicated only consonants, but certain letters, known by the Latin term matres lectionis, became increasingly used to mark vowels. In the Middle Ages, various systems of diacritics were developed to mark the vowels in Hebrew manuscripts; of these, only the Tiberian vocalization is still in wide use.

Biblical Hebrew possessed a series of emphatic consonants whose precise articulation is disputed, likely ejective or pharyngealized. Earlier Biblical Hebrew possessed three consonants which did not have their own letters in the writing system, but over time they merged with other consonants. The stop consonants developed fricative allophones under the influence of Aramaic, and these sounds eventually became marginally phonemic. The pharyngeal and glottal consonants underwent weakening in some regional dialects, as reflected in the modern Samaritan Hebrew reading tradition. The vowel system of Biblical Hebrew changed over time and is reflected differently in the ancient Greek and Latin transcriptions, medieval vocalization systems, and modern reading traditions.

Biblical Hebrew had a typical Semitic morphology with nonconcatenative morphology, arranging Semitic roots into patterns to form words. Biblical Hebrew distinguished two genders (masculine, feminine), three numbers (singular, plural, and uncommonly, dual). Verbs were marked for voice and mood, and had two conjugations which may have indicated aspect and/or tense (a matter of debate). The tense or aspect of verbs was also influenced by the conjunction ו, in the so-called waw-consecutive construction. Unlike modern Hebrew, the default word order for biblical Hebrew was verb–subject–object, and verbs inflected for the number, gender, and person of their subject. Pronominal suffixes could be appended to verbs (to indicate object) or nouns (to indicate possession), and nouns had special construct states for use in possessive constructions.

Nomenclature[edit]

The earliest written sources refer to Biblical Hebrew as שפת כנען "the language of Canaan".[4][5] The Hebrew Bible also calls the language יהודית "Judaean, Judahite"[6][5] In the Hellenistic period, Greek writings use the names Hebraios, Hebraïsti[7] and in Mishnaic Hebrew we find עברית 'Hebrew' and לשון עברית "Hebrew language".[8][5] The origin of this term is obscure; suggested origins include the biblical Eber, the ethnonyms Ḫabiru, Ḫapiru, and ˁApiru found in sources from Egypt and the near east, and a derivation from the root עבר "to pass" alluding to crossing over the Jordan River.[5][9] Jews also began referring to Hebrew as לשון הקדש "the Holy Tongue" in Mishnaic Hebrew.[5]

The term Classical Hebrew may include all pre-medieval dialects of Hebrew, including Mishnaic Hebrew, or it may be limited to Hebrew contemporaneous with the Hebrew Bible. The term Biblical Hebrew refers to pre-Mishnaic dialects (sometimes excluding Dead Sea Scroll Hebrew). The term Biblical Hebrew may or may not include extra-biblical texts, such as inscriptions (e.g. the Siloam inscription), and generally also includes later vocalization traditions for the Hebrew Bible's consonantal text, most commonly the early medieval Tiberian vocalization.

Eras[edit]

Biblical Hebrew as preserved in the Hebrew Bible is composed of multiple linguistic layers. The consonantal skeleton of the text is the most ancient, while the cantillation and modern vocalization are later additions reflecting a later stage of the language.[19] These additions were added after 600 CE; Hebrew had already ceased being used as a spoken language around 200 CE.[38] Biblical Hebrew as reflected in the consonantal text of the Bible and in extra-biblical inscriptions may be subdivided by era.

The oldest form of Biblical Hebrew, Archaic Hebrew, is found in poetic sections of the Bible and inscriptions dating to around 1000 BCE, the early Monarchic Period.[39][40] This stage is also known as Old Hebrew or Paleo-Hebrew, and is the oldest stratum of Biblical Hebrew. The oldest known artifacts of Archaic Biblical Hebrew are various sections of the Tanakh, including the Song of Moses (Exodus 15) and the Song of Deborah (Judges 5).[41] Biblical poetry uses a number of distinct lexical items, for example חזה for prose ראה 'see', כביר for גדול 'great'.[42] Some have cognates in other Northwest Semitic languages, for example פעל 'do' and חָרוּץ 'gold' which are common in Canaanite and Ugaritic.[43] Grammatical differences include the use of זה, זוֹ, and זוּ as relative particles, negative בל, and various differences in verbal and pronominal morphology and syntax.[44]

Later pre-exilic Biblical Hebrew (such as is found in prose sections of the Pentateuch, Nevi'im, and some Ketuvim) is known as 'Biblical Hebrew proper' or 'Standard Biblical Hebrew'.[39][40] This is dated to the period from the 8th to the 6th century BCE. In contrast to Archaic Hebrew, Standard Biblical Hebrew is more consistent in using the definite article ה-, the accusative marker את, distinguishing between simple and waw-consecutive verb forms, and in using particles like אשר and כי rather than asyndeton.[45]

Biblical Hebrew from after the Babylonian exile in 587 BCE is known as 'Late Biblical Hebrew'.[39][40] Late Biblical Hebrew shows Aramaic influence in phonology, morphology, and lexicon, and this trend is also evident in the later-developed Tiberian vocalization system.[46][nb 4]

Qumran Hebrew, attested in the Dead Sea Scrolls from ca. 200 BCE to 70 CE, is a continuation of Late Biblical Hebrew.[40] Qumran Hebrew may be considered an intermediate stage between Biblical Hebrew and Mishnaic Hebrew, though Qumran Hebrew shows its own idiosyncratic dialectal features.[47]

Dialects[edit]

Dialect variation in Biblical Hebrew is attested to by the well-known shibboleth incident of Judges 12:6, where Jephthah's forces from Gilead caught Ephraimites trying to cross the Jordan river by making them say שִׁבֹּ֤לֶת šibboleṯ ('ear of corn')[48] The Ephraimites' identity was given away by their pronunciation: סִבֹּ֤לֶת sibboleṯ.[48] The apparent conclusion is that the Ephraimite dialect had /s/ for standard /ʃ/.[48] As an alternative explanation, it has been suggested that the proto-Semitic phoneme */θ/, which shifted to /ʃ/ in most dialects of Hebrew, may have been retained in the Hebrew of the trans-Jordan[49][nb 5] (however, there is evidence that שִׁבֹּ֤לֶת's Proto-Semitic ancestor had initial consonant š (whence Hebrew /ʃ/), contradicting this theory;[48] for example, שִׁבֹּ֤לֶת's Proto-Semitic ancestor has been reconstructed as *šu(n)bul-at-.[50]); or that the Proto-Semitic sibilant *s1, transcribed with šin and traditionally reconstructed as */ʃ/, had been originally */s/ while another sibilant *s3, transcribed with sameḵ and traditionally reconstructed as /s/, had been originally /ts/;[51] later on, a push-type chain shift changed *s3 /ts/ to /s/ and pushed s1 /s/ to /ʃ/ in many dialects (e.g. Gileadite) but not others (e.g. Ephraimite), where *s1 and *s3 merged into /s/.

Hebrew as spoken in the northern Kingdom of Israel, known also as Israelian Hebrew, shows phonological, lexical, and grammatical differences from southern dialects.[52] The Northern dialect spoken around Samaria shows more frequent simplification of /aj/ into /eː/ as attested by the Samaria ostraca (8th century BCE), e.g. ין (= /jeːn/ < */jajn/ 'wine'), while the Southern (Judean) dialect instead adds in an epenthetic vowel /i/, added halfway through the first millennium BCE (יין = /ˈjajin/).[30][nb 6][53] The word play in Amos 8:1–2 כְּלוּב קַ֫יִץ... בָּא הַקֵּץ may reflect this: given that Amos was addressing the population of the Northern Kingdom, the vocalization *קֵיץ would be more forceful.[53] Other possible Northern features include use of שֶ- 'who, that', forms like דֵעָה 'to know' rather than דַעַת and infinitives of certain verbs of the form עֲשוֹ 'to do' rather than עֲשוֹת.[54] The Samaria ostraca also show שת for standard שנה 'year', as in Aramaic.[54]

The guttural phonemes /ħ ʕ h ʔ/ merged over time in some dialects.[55] This was found in Dead Sea Scroll Hebrew, but Jerome attested to the existence of contemporaneous Hebrew speakers who still distinguished pharyngeals.[55] Samaritan Hebrew also shows a general attrition of these phonemes, though /ʕ ħ/ are occasionally preserved as [ʕ].[56]