Medieval art

The medieval art of the Western world covers a vast scope of time and place, with over 1000 years of art in Europe, and at certain periods in Western Asia and Northern Africa. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional art, genres, revivals, the artists' crafts, and the artists themselves.

Art historians attempt to classify medieval art into major periods and styles, often with some difficulty. A generally accepted scheme includes the later phases of Early Christian art, Migration Period art, Byzantine art, Insular art, Pre-Romanesque, Romanesque art, and Gothic art, as well as many other periods within these central styles. In addition, each region, mostly during the period in the process of becoming nations or cultures, had its own distinct artistic style, such as Anglo-Saxon art or Viking art.

Medieval art was produced in many media, and works survive in large numbers in sculpture, illuminated manuscripts, stained glass, metalwork and mosaics, all of which have had a higher survival rate than other media such as fresco wall-paintings, work in precious metals or textiles, including tapestry. Especially in the early part of the period, works in the so-called "minor arts" or decorative arts, such as metalwork, ivory carving, vitreous enamel and embroidery using precious metals, were probably more highly valued than paintings or monumental sculpture.[1]

Medieval art in Europe grew out of the artistic heritage of the Roman Empire and the iconographic traditions of the early Christian church. These sources were mixed with the vigorous "barbarian" artistic culture of Northern Europe to produce a remarkable artistic legacy. Indeed, the history of medieval art can be seen as the history of the interplay between the elements of classical, early Christian and "barbarian" art.[2] Apart from the formal aspects of classicism, there was a continuous tradition of realistic depiction of objects that survived in Byzantine art throughout the period, while in the West it appears intermittently, combining and sometimes competing with new expressionist possibilities developed in Western Europe and the Northern legacy of energetic decorative elements. The period ended with the self-perceived Renaissance recovery of the skills and values of classical art, and the artistic legacy of the Middle Ages was then disparaged for some centuries. Since a revival of interest and understanding in the 19th century it has been seen as a period of enormous achievement that underlies the development of later Western art.

Early Christian art, more generally described as Late Antique art, covers the period from about 200 (before which no distinct Christian art survives), until the onset of a fully Byzantine style in about 500. There continue to be different views as to when the medieval period begins during this time, both in terms of general history and specifically art history, but it is most often placed late in the period. In the course of the 4th century Christianity went from being a persecuted popular sect to the official religion of the Empire, adapting existing Roman styles and often iconography, from both popular and Imperial art. From the start of the period the main survivals of Christian art are the tomb-paintings in popular styles of the catacombs of Rome, but by the end there were a number of lavish mosaics in churches built under Imperial patronage.

Over this period imperial Late Roman art went through a strikingly "baroque" phase, and then largely abandoned classical style and Greek realism in favour of a more mystical and hieratic style—a process that was well underway before Christianity became a major influence on imperial art. Influences from Eastern parts of the Empire—Egypt, Syria and beyond, and also a robust "Italic" vernacular tradition, contributed to this process.

Figures are mostly seen frontally staring out at the viewer, where classical art tended to show a profile view - the change was eventually seen even on coins. The individuality of portraits, a great strength of Roman art, declines sharply, and the anatomy and drapery of figures is shown with much less realism. The models from which medieval Northern Europe in particular formed its idea of "Roman" style were nearly all portable Late Antique works, and the Late Antique carved sarcophagi found all over the former Roman Empire;[11] the determination to find earlier "purer" classical models, was a key element in the art all'antica of the Renaissance.[12]

Ivory reliefs

African Medieval Art[edit]

Often overlooked in reviews of medieval art are the works of the African continent. Among these are the arts of Egypt, Nubia, and Ethiopia. After the African churches refused the Council of Chalcedon and became the Oriental Orthodox Churches, their art developed in new directions, related to Byzantium but different from it.

Coptic art arose from indigenous Egyptian conceptions, with a non-realist style, often with large-eyed figures floating on unpainted backgrounds. Coptic decoration used intricate geometric designs, which Islamic art later followed. Because of the exceptionally good preservation of Egyptian burials, we know more about the textiles used by the less well-off in Egypt than anywhere else. These were often elaborately decorated with figurative and patterned designs.

Ethiopian art was a vital part of the Aksumite empire, with one important example being the Garima Gospels, among the earliest illustrated biblical manuscripts anywhere. Works about the Virgin Mary were especially likely to be illustrated, as demonstrated by a royal manuscript known as EMML 9002 created at the end of the 1300s.[15] Some of these images of Mary can be viewed at the Princeton Ethiopian, Eritrean and Egyptian Miracles of Mary project.[16]

Migration Period art describes the art of the "barbarian" Germanic and Eastern-European peoples who were on the move, and then settling within the former Roman Empire, during the Migration Period from about 300-700; the blanket term covers a wide range of ethnic or regional styles including early Anglo-Saxon art, Visigothic art, Viking art, and Merovingian art, all of which made use of the animal style as well as geometric motifs derived from classical art. By this period the animal style had reached a much more abstracted form than in earlier Scythian art or La Tène style. Most artworks were small and portable and those surviving are mostly jewellery and metalwork, with the art expressed in geometric or schematic designs, often beautifully conceived and made, with few human figures and no attempt at realism. The early Anglo-Saxon grave goods from Sutton Hoo are among the best examples.

As the "barbarian" peoples were Christianised, these influences interacted with the post-classical Mediterranean Christian artistic tradition, and new forms like the illuminated manuscript,[17] and indeed coins, which attempted to emulate Roman provincial coins and Byzantine types. Early coinage like the sceat shows designers completely unused to depicting a head in profile grappling with the problem in a variety of different ways.

As for larger works, there are references to Anglo-Saxon wooden pagan statues, all now lost, and in Norse art the tradition of carved runestones was maintained after their conversion to Christianity. The Celtic Picts of Scotland also carved stones before and after conversion, and the distinctive Anglo-Saxon and Irish tradition of large outdoor carved crosses may reflect earlier pagan works. Viking art from later centuries in Scandinavia and parts of the British Isles includes work from both pagan and Christian backgrounds, and was one of the last flowerings of this broad group of styles.

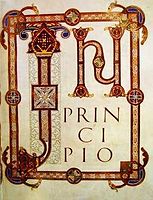

Insular art refers to the distinct style found in Ireland and Britain from about the 7th century, to about the 10th century, lasting later in Ireland, and parts of Scotland. The style saw a fusion between the traditions of Celtic art, the Germanic Migration period art of the Anglo-Saxons and the Christian forms of the book, high crosses and liturgical metalwork.

Extremely detailed geometric, interlace, and stylised animal decoration, with forms derived from secular metalwork like brooches, spread boldly across manuscripts, usually gospel books like the Book of Kells, with whole carpet pages devoted to such designs, and the development of the large decorated and historiated initial. There were very few human figures—most often these were Evangelist portraits—and these were crude, even when closely following Late Antique models.

The insular manuscript style was transmitted to the continent by the Hiberno-Scottish mission, and its anti-classical energy was extremely important in the formation of later medieval styles. In most Late Antique manuscripts text and decoration were kept clearly apart, though some initials began to be enlarged and elaborated, but major insular manuscripts sometimes take a whole page for a single initial or the first few words (see illustration) at beginnings of gospels or other sections in a book. Allowing decoration a "right to roam" was to be very influential on Romanesque and Gothic art in all media.

The buildings of the monasteries for which the insular gospel books were made were then small and could fairly be called primitive, especially in Ireland. There increasingly were other decorations to churches, where possible in precious metals, and a handful of these survive, like the Ardagh Chalice, together with a larger number of extremely ornate and finely made pieces of secular high-status jewellery, the Celtic brooches probably worn mainly by men, of which the Tara Brooch is the most spectacular.

"Franco-Saxon" is a term for a school of late Carolingian illumination in north-eastern France that used insular-style decoration, including super-large initials, sometimes in combination with figurative images typical of contemporary French styles. The "most tenacious of all the Carolingian styles", it continued until as late as the 11th century.[18]

Giant initials

Pre-Romanesque is a term for architecture and to some extent pictorial and portable art found initially in Southern Europe (Spain, Italy and Southern France) between the Late Antique period to the start of the Romanesque period in the 11th century. Northern European art gradually forms part of the movement after Christianisation as it assimilates post-classical styles. The Carolingian art of the Frankish Empire, especially modern France and Germany, from roughly 780-900 takes its name from Charlemagne and is an art of the court circle and a few monastic centres under Imperial patronage, that consciously sought to revive "Roman" styles and standards as befitted the new Empire of the West. Some centres of Carolingian production also pioneered expressive styles in works like the Utrecht Psalter and Ebbo Gospels. Christian monumental sculpture is recorded for the first time, and depiction of the human figure in narrative scenes became confident for the first time in Northern art. Carolingian architecture produced larger buildings than had been seen since Roman times, and the westwork and other innovations.[31]

After the collapse of the dynasty there was a hiatus before a new dynasty brought a revival in Germany with Ottonian art, again centred on the court and monasteries, with art that moved towards great expressiveness through simple forms that achieve monumentality even in small works like ivory reliefs and manuscript miniatures, above all those of the Reichenau School, such as the Pericopes of Henry II (1002–1012). Later Anglo-Saxon art in England, from about 900, was expressive in a very different way, with agitated figures and even drapery perhaps best shown in the many pen drawings in manuscripts. The Mozarabic art of Christian Spain had strong Islamic influence, and a complete lack of interest in realism in its brilliantly coloured miniatures, where figures are presented as entirely flat patterns. Both of these were to influence the formation in France of the Romanesque style.[32]

Romanesque art developed in the period between about 1000 to the rise of Gothic art in the 12th century, in conjunction with the rise of monasticism in Western Europe. The style developed initially in France, but spread to Christian Spain, England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, and elsewhere to become the first medieval style found all over Europe, though with regional differences.[34] The arrival of the style coincided with a great increase in church-building, and in the size of cathedrals and larger churches; many of these were rebuilt in subsequent periods, but often reached roughly their present size in the Romanesque period. Romanesque architecture is dominated by thick walls, massive structures conceived as a single organic form, with vaulted roofs and round-headed windows and arches.

Figurative sculpture, originally colourfully painted, plays an integral and important part in these buildings, in the capitals of columns, as well as around impressive portals, usually centred on a tympanum above the main doors, as at Vézelay Abbey and Autun Cathedral. Reliefs are much more common than free-standing statues in stone, but Romanesque relief became much higher, with some elements fully detached from the wall behind. Large carvings also became important, especially painted wooden crucifixes like the Gero Cross from the very start of the period, and figures of the Virgin Mary like the Golden Madonna of Essen. Royalty and the higher clergy began to commission life-size effigies for tomb monuments. Some churches had massive pairs of bronze doors decorated with narrative relief panels, like the Gniezno Doors or those at Hildesheim, "the first decorated bronze doors cast in one piece in the West since Roman times", and arguably the finest before the Renaissance.[35]

Most churches were extensively frescoed; a typical scheme had Christ in Majesty at the east (altar) end, a Last Judgement at the west end over the doors, and scenes from the Life of Christ facing typologically matching Old Testament scenes on the nave walls. The "greatest surviving monument of Romanesque wall painting", much reduced from what was originally there, is in the Abbey Church of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe near Poitiers, where the rounded barrel vault of the nave, the crypt, portico and other areas retain most of their paintings.[36] An equivalent cycle in Sant'Angelo in Formis at Capua in southern Italy by Italian painters trained by Greeks illustrates the continuing predominance of Byzantine style in much of Italy.[37]

Romanesque sculpture and painting is often vigorous and expressive, and inventive in terms of iconography—the subjects chosen and their treatment. Though many features absorbed from classical art form part of the Romanesque style, Romanesque artists rarely intended to achieve any sort of classical effect, except perhaps in Mosan art.[38] As art became seen by a wider section of the population, and because of challenges from new heresies, art became more didactic, and the local church the "Poor Man's Bible". At the same time grotesque beasts and monsters, and fights with or between them, were popular themes, to which religious meanings might be loosely attached, although this did not impress St Bernard of Clairvaux, who famously denounced such distractions in monasteries:

He might well have known the miniature at left, which was produced at Cîteaux Abbey before the young Bernard was transferred from there in 1115.[40]

During the period typology became the dominant approach in theological literature and art to interpreting the bible, with Old Testament incidents seen as pre-figurations of aspects of the life of Christ, and shown paired with their corresponding New Testament episode. Often the iconography of the New Testament scene was based on traditions and models originating in Late Antiquity, but the iconography of the Old Testament episode had to be invented in this period, for lack of precedents. New themes such as the Tree of Jesse were devised, and representations of God the Father became more acceptable. The vast majority of surviving art is religious. Mosan art was an especially refined regional style, with much superb metalwork surviving, often combined with enamel, and elements of classicism rare in Romanesque art, as in the Baptismal font at St Bartholomew's Church, Liège, or the Shrine of the Three Kings at Cologne, one of a number of surviving works by Nicholas of Verdun, whose services were sought across north-western Europe.

Stained glass became a significant art-form in the period, though little Romanesque glass survives. In illuminated manuscripts the bible became a new focus of intensive decoration, with the psalter also remaining important. The strong emphasis on the suffering of Christ and other sacred figures entered Western art in this period, a feature that strongly distinguishes it from both Byzantine and classical art for the remainder of the Middle Ages and beyond. The Gero Cross of 965-970, at the cusp of Ottonian and Romanesque art, has been called the first work to exhibit this.[41] The end of the Romanesque period saw the start of the greatly increased emphasis on the Virgin Mary in theology, literature and so also art that was to reach its full extent in the Gothic period.

Gothic art is a variable term depending on the craft, place and time. The term originated with the Gothic architecture which developed in France from about 1137 with the rebuilding of the Abbey Church of St Denis. As with Romanesque architecture, this included sculpture as an integral part of the style, with even larger portals and other figures on the facades of churches the location of the most important sculpture, until the late period, when large carved altarpieces and reredos, usually in painted and gilded wood, became an important focus in many churches. Gothic painting did not appear until around 1200 (this date has many qualifications), when it diverged from Romanesque style. A Gothic style in sculpture originates in France around 1144 and spread throughout Europe, becoming by the 13th century the international style, replacing Romanesque, though in sculpture and painting the transition was not as sharp as in architecture.

The majority of Romanesque cathedrals and large churches were replaced by Gothic buildings, at least in those places benefiting from the economic growth of the period—Romanesque architecture is now best seen in areas that were subsequently relatively depressed, like many southern regions of France and Italy, or northern Spain. The new architecture allowed for much larger windows, and stained glass of a quality never excelled is perhaps the type of art most associated in the popular mind with the Gothic, although churches with nearly all their original glass, like the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, are extremely rare anywhere, and unknown in Britain.

Most Gothic wall-paintings have also disappeared; these remained very common, though in parish churches often rather crudely executed. Secular buildings also often had wall-paintings, although royalty preferred the much more expensive tapestries, which were carried along as they travelled between their many palaces and castles, or taken with them on military campaigns—the finest collection of late-medieval textile art comes from the Swiss booty at the Battle of Nancy, when they defeated and killed Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, and captured all his baggage train.[43]

As mentioned in the previous section, the Gothic period coincided with a greatly increased emphasis on the Virgin Mary, and it was in this period that the Virgin and Child became such a hallmark of Catholic art. Saints were also portrayed far more often, and many of the range of attributes developed to identify them visually for a still largely illiterate public first appeared.

During this period panel painting for altarpieces, often polyptyches and smaller works became newly important. Previously icons on panels had been much more common in Byzantine art than in the West, although many now lost panel paintings made in the West are documented from much earlier periods, and initially Western painters on panel were very largely under the sway of Byzantine models, especially in Italy, from where most early Western panel paintings come. The process of establishing a distinct Western style was begun by Cimabue and Duccio, and completed by Giotto, who is traditionally regarded as the starting point for the development of Renaissance painting. Most panel painting remained more conservative than miniature painting however, partly because it was seen by a wide public.

International Gothic describes courtly Gothic art from about 1360 to 1430, after which Gothic art begins to merge into the Renaissance art that had begun to form itself in Italy during the Trecento, with a return to classical principles of composition and realism, with the sculptor Nicola Pisano and the painter Giotto as especially formative figures. The Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is one of the best known works of International Gothic. The transition to the Renaissance occurred at different times in different places - Early Netherlandish painting is poised between the two, as is the Italian painter Pisanello. Outside Italy Renaissance styles appeared in some works in courts and some wealthy cities while other works, and all work beyond these centres of innovation, continued late Gothic styles for a period of some decades. The Protestant Reformation often provided an end point for the Gothic tradition in areas that went Protestant, as it was associated with Catholicism.

The invention of a comprehensive mathematically based system of linear perspective is a defining achievement of the early-15th-century Italian Renaissance in Florence, but Gothic painting had already made great progress in the naturalistic depiction of distance and volume, though it did not usually regard them as essential features of a work if other aims conflicted with them, and late Gothic sculpture was increasingly naturalistic. In the mid-15th century Burgundian miniature (right) the artist seems keen to show his skill at representing buildings and blocks of stone obliquely, and managing scenes at different distances. But his general attempt to reduce the size of more distant elements is unsystematic. Sections of the composition are at a similar scale, with relative distance shown by overlapping, foreshortening, and further objects being higher than nearer ones, though the workmen at left do show finer adjustment of size. But this is abandoned on the right where the most important figure is much larger than the mason.

The end of the period includes new media such as prints; along with small panel paintings these were frequently used for the emotive andachtsbilder ("devotional images") influenced by new religious trends of the period. These were images of moments detached from the narrative of the Passion of Christ designed for meditation on his sufferings, or those of the Virgin: the Man of Sorrows, Pietà, Veil of Veronica or Arma Christi. The trauma of the Black Death in the mid-14th century was at least partly responsible for the popularity of themes such as the Dance of Death and Memento mori. In the cheap blockbooks with text (often in the vernacular) and images cut in a single woodcut, works such as that illustrated (left), the Ars Moriendi (Art of Dying) and typological verse summaries of the bible like the Speculum Humanae Salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation) were the most popular.

Renaissance Humanism and the rise of a wealthy urban middle class, led by merchants, began to transform the old social context of art, with the revival of realistic portraiture and the appearance of printmaking and the self-portrait, together with the decline of forms like stained glass and the illuminated manuscript. Donor portraits, in the Early Medieval period largely the preserve of popes, kings and abbots, now showed businessmen and their families, and churches were becoming crowded with the tomb monuments of the well-off.

The book of hours, a type of manuscript normally owned by laymen, or even more often, laywomen, became the type of manuscript most often heavily illustrated from the 14th century onwards, and also by this period, the lead in producing miniatures had passed to lay artists, also very often women. In the most important centres of illumination, Paris and in the 15th century the cities of Flanders, there were large workshops, exporting to other parts of Europe. Other forms of art, such as small ivory reliefs, stained glass, tapestries and Nottingham alabasters (cheap carved panels for altarpieces) were produced in similar conditions, and artists and craftsmen in cities were usually covered by the guild system—the goldsmith's guild was typically among the richest in a city, and painters were members of a special Guild of St Luke in many places.

Secular works, often using subjects concerned with courtly love or knightly heroism, were produced as illuminated manuscripts, carved ivory mirror-cases, tapestries and elaborate gold table centrepieces like nefs. It begins to be possible to distinguish much greater numbers of individual artists, some of whom had international reputations. Art collectors begin to appear, of manuscripts among the great nobles, like John, Duke of Berry (1340–1416) and of prints and other works among those with moderate wealth. In the wealthier areas tiny cheap religious woodcuts brought art in an approximation of the latest style even into the homes of peasants by the late 15th century.

Virgin Mary

![Another Carolingian evangelist portrait in Greek/Byzantine realist style, probably by a Greek artist, also late 8th century.[33]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/Coronation_Gospels_-_St_John.png/160px-Coronation_Gospels_-_St_John.png)

![The 12th-century frescos in St Botolph's Church, England, are part of the 'Lewes Group' of Romanesque paintings created for Lewes Priory.[42]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c6/Hardham_church%2C_interior.jpg/200px-Hardham_church%2C_interior.jpg)