Treaty of San Francisco

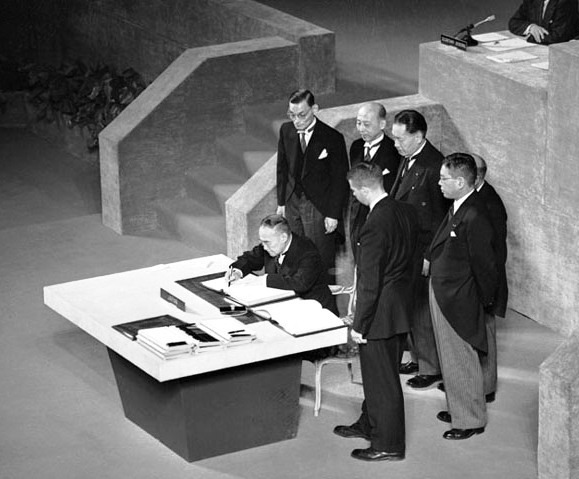

The Treaty of San Francisco (サンフランシスコ講和条約, San-Furanshisuko kōwa-Jōyaku), also called the Treaty of Peace with Japan (日本国との平和条約, Nihon-koku to no Heiwa-Jōyaku), re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It was signed by 49 nations on 8 September 1951, in San Francisco, California, at the War Memorial Opera House.[2] Italy and China were not invited, the latter due to disagreements on whether the Republic of China or the People's Republic of China represented the Chinese people. Korea was also not invited due to a similar disagreement on whether South Korea or North Korea represented the Korean people.[3]

Not to be confused with Security Treaty between the United States and Japan or United Nations charter.Treaty of Peace with Japan

8 September 1951

San Francisco, California, U.S.

28 April 1952

- US: John Foster Dulles

- Japan: Shigeru Yoshida

Japan and 48 of the Allies of World War II

The treaty came into force on 28 April 1952. It ended Japan's role as an imperial power, allocated compensation to Allied nations and former prisoners of war who had suffered Japanese war crimes during World War II, ended the Allied post-war occupation of Japan, and returned full sovereignty to it. This treaty relied heavily on the Charter of the United Nations[4] and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights[5] to enunciate the Allies' goals. In Article 11, Japan accepted the judgments of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and of other Allied War Crimes Courts imposed on Japan both within and outside Japan.[6]

The 1951 treaty, along with the Security Treaty signed that same day, marks the beginning of the San Francisco System, which defines Japan's relationship with the United States and its role in the international arena and characterizes Japan's post-war history.[7]

Attendance[edit]

Present[edit]

Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Cambodia, Canada, Ceylon (currently Sri Lanka), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, El Salvador, Ethiopia, France, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Japan, Laos, Lebanon, Liberia, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, the Philippines, Poland, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, State of Vietnam, the Soviet Union, Syria, Turkey, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uruguay, and Venezuela attended the Conference.[8]

Absent[edit]

China was not invited due to disagreements between the United States and Great Britain on whether the established but defeated Republic of China (in Taiwan) or the newly-formed People's Republic of China (in mainland China) represented the Chinese people.[9] The United States recognized the ROC government while Britain had recognized the PRC in 1950.[9] Additionally, an internal US political debate had seen the Republican Party and US military supporting the Kuomintang party and accusing President Truman of having abandoned the anti-communism cause.[10]

The absence of China at the table would later play a significant role in the South China Sea dispute, specifically regarding the overall diplomatic relationship (or lack thereof) between the United States and China.[9] According to historian Rana Mitter, "The absence of contact between the United States and China made the establishment of shared norms, or even areas of mutually acknowledged difference, impossible."[9]

Burma, India, and Yugoslavia were invited, but did not participate;[11] India considered certain provisions of the treaty to constitute limitations on Japanese sovereignty and national independence.[12] India signed a separate peace treaty, the Treaty of Peace Between Japan and India, for the purpose of giving Japan a proper position of honor and equality among the community of free nations, on June 9, 1952.[13] Italy was not invited, despite its government having issued a formal declaration of war on Japan on July 14, 1945, just a few weeks before the end of the war.[14] Nor was Portugal invited, even though, despite its status as a neutral country during the war, its territory of East Timor had been invaded by Japan. Pakistan, although it had not existed as a state at the time of the war, was invited because it was seen as a successor state to British India, a major combatant against Japan.[15]

Stances[edit]

Soviet Union's opposition to the treaty[edit]

The Soviet Union took part in the San Francisco conference, and the Soviet delegation was led by the Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko. From the start of the conference the Soviet Union expressed vigorous and vocal opposition to the draft treaty text prepared by the United States and the United Kingdom. The Soviet delegation made several unsuccessful procedural attempts to stall the proceedings.[16] The Soviet Union's objections were detailed in a lengthy 8 September 1951, statement by Gromyko.[17] The statement contained a number of the Soviet Union's claims and assertions: that the treaty did not provide any guarantees against the rise of Japanese militarism; that China was not invited to participate despite being one of the main victims of the Japanese aggression; that the Soviet Union was not properly consulted when the treaty was being prepared; that the treaty sets up Japan as an American military base and draws Japan into a military coalition directed against the Soviet Union; that the treaty was in effect a separate peace treaty; that the draft treaty violated the rights of China to Taiwan and several other islands; that the draft treaty, in violation of the Yalta agreement, did not recognize the Soviet Union's sovereignty over South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands; and other objections. It was not until 19 October 1956, that Japan and the Soviet Union signed a Joint Declaration ending the war and reestablishing diplomatic relations.[18]

People's Republic of China's objections to the treaty[edit]

The ongoing Chinese Civil War and thus the question of which Chinese government was legitimate presented a dilemma to conference organizers. The United States wanted to invite the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan to represent China, while the United Kingdom wished to invite the People's Republic of China (PRC) on mainland China as China's representative.[9] As a compromise, neither government was invited.

Sri Lanka's defense of Japan[edit]

A major player in providing support for a post-war free Japan was the delegation from Ceylon (now known as Sri Lanka).[19] While many were reluctant to allow a free Japan capable of aggressive action and insisted that the terms of surrender should be rigidly enforced in an attempt to break the spirit of the Japanese nation, the Ceylonese Finance Minister J.R. Jayawardene spoke in defense of a free Japan and informed the conference of Ceylon's refusal to accept the payment of reparations that would harm Japan's economy. His reason was "We in Ceylon were fortunate that we were not invaded, but the damage caused by air raids, by the stationing of enormous armies under the South-East Asia Command, and by the slaughter-tapping of one of our main commodities, rubber, when we were the only producer of natural rubber for the Allies, entitles us to ask that the damage so caused should be repaired. We do not intend to do so for we believe in the words of the Great Teacher [Buddha] whose message has ennobled the lives of countless millions in Asia, that 'hatred ceases not by hatred but by love'." He ended the same speech by saying:

Minister Jayewardene's speech was received with resounding applause.[22] Afterwards, the New York Times stated, "The voice of free Asia, eloquent, melancholy and still strong with the lilt of an Oxford accent, dominated the Japanese peace treaty conference today."[23]

Fate of Taiwan and other Japanese overseas territories[edit]

According to the treaty's travaux préparatoires, a consensus existed among the states present at the San Francisco Peace Conference that, while the legal status of the island of Taiwan is temporarily undetermined, it would be resolved at a later time in accordance with the principles of peaceful settlement of disputes and self-determination, ideas that had been enshrined in the UN Charter.[30]

The document officially renounces Japan's treaty rights derived from the Boxer Protocol of 1901 and its rights to Korea, Formosa and the Pescadores, Hong Kong (then a British colony), the Kuril Islands, the Spratly Islands, Antarctica and South Sakhalin.

Article 3 of the treaty left the Bonin Islands, Volcano Islands (including Iwo Jima), and the Ryukyu Islands, which included Okinawa and the Amami, Miyako and Yaeyama Islands groups, under a potential U.N. trusteeship. While the treaty provision implied that these territories would become a United Nations trusteeship, in the end that option was not pursued. The Amami Islands were eventually restored to Japan on 25 December 1953, with the Bonin and Volcano Islands restored on 5 April 1968.[31] In 1969 U.S.-Japan negotiations authorized the transfer of authority over the Ryūkyūs to Japan to be implemented in 1972. In 1972, the United States' "reversion" of the Ryūkyūs occurred along with the ceding of control over the nearby Senkaku Islands.[32] Both the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC) argue that this agreement did not determine the ultimate sovereignty of the Senkaku Islands.

The Treaty of Taipei between Japan and the ROC stated that all residents of Taiwan and the Pescadores were deemed as nationals of the ROC. Additionally, in Article 2 it specified that –

It is recognised that under Article 2 of the Treaty of Peace which Japan signed at the city of San Francisco on 8 September 1951 (hereinafter referred to as the San Francisco Treaty), Japan has renounced all right, title, and claim to Taiwan (Formosa) and Penghu (the Pescadores) as well as the Spratley Islands and the Paracel Islands.[33] However, this treaty does not include any wording saying that Japan recognizes that the territorial sovereignty of Taiwan was transferred to the Republic of China.[34]

Some supporters of Taiwan independence refer to the San Francisco Peace Treaty to argue that Taiwan is not a part of the Republic of China, for it does not explicitly state the sovereignty status of Taiwan after Japan's renunciation.[35] In 1955, U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, co-author of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, affirmed that the treaty ceded Taiwan to no one; that Japan "merely renounced sovereignty over Taiwan".[36] Dulles said that America "cannot, therefore, admit that the disposition of Taiwan is merely an internal problem of China."[36] However, the ROC Ministry of Foreign Affairs rejected this justification, arguing that the Instrument of Surrender of Japan accepts the Potsdam Declaration and the Cairo Declaration, which intends Taiwan and Penghu to be restored to the ROC. Supporters of Taiwan independence point out that the Potsdam Declaration and the Cairo Declaration were not treaties, but President Ma expressed that the Treaty of Taipei has voided the Treaty of Shimonoseki and recognizes that people of Taiwan and Penghu as Chinese nationality.[35] In more recent years supporters of Taiwan independence have more often relied on arguments based on self-determination as implied in the San Francisco Peace Treaty and popular sovereignty, but the United Nations has consistently rejected such arguments.[37]

By Article 11 Japan accepted the judgments of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and of other Allied War Crimes Courts both within and outside Japan and agreed to carry out the sentences imposed thereby upon Japanese nationals imprisoned in Japan.

The document further set guidelines for repatriation of Allied prisoners of war and renounces future military aggression under the guidelines set by the United Nations Charter. The document nullifies prior treaties and lays down the framework for Japan's current status of retaining a military that is purely defensive in nature.

There is also some ambiguity as to over which islands Japan has renounced sovereignty. This has led to both the Kuril Islands dispute and the Senkaku Islands dispute.

Germany: