Modern architecture

Modern architecture, also called modernist architecture, was an architectural movement and style that was prominent in the 20th century, between the earlier Art Deco and later postmodern movements. Modern architecture was based upon new and innovative technologies of construction (particularly the use of glass, steel, and concrete); the principle functionalism (i.e. that form should follow function); an embrace of minimalism; and a rejection of ornament.[1]

This article is about modern movement architecture. For architecture in the present day, see contemporary architecture.Years active

1920s–1980s

International

According to Le Corbusier, the roots of the movement were to be found in the works of Eugène Viollet le duc.[2] The movement emerged in the first half of the 20th century and became dominant after World War II until the 1980s, when it was gradually replaced as the principal style for institutional and corporate buildings by postmodern architecture.[3]

Modern architecture emerged at the end of the 19th century from revolutions in technology, engineering, and building materials, and from a desire to break away from historical architectural styles and invent something that was purely functional and new.

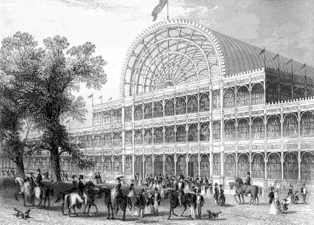

The revolution in materials came first, with the use of cast iron, drywall, plate glass, and reinforced concrete, to build structures that were stronger, lighter, and taller. The cast plate glass process was invented in 1848, allowing the manufacture of very large windows. The Crystal Palace by Joseph Paxton at the Great Exhibition of 1851 was an early example of iron and plate glass construction, followed in 1864 by the first glass and metal curtain wall. These developments together led to the first steel-framed skyscraper, the ten-story Home Insurance Building in Chicago, built in 1884 by William Le Baron Jenney[4] and based on the works of Viollet le Duc.

French industrialist François Coignet was the first to use iron-reinforced concrete, that is, concrete strengthened with iron bars, as a technique for constructing buildings.[5] In 1853 Coignet built the first iron reinforced concrete structure, a four-storey house in the suburbs of Paris.[5] A further important step forward was the invention of the safety elevator by Elisha Otis, first demonstrated at the New York Crystal Palace exposition in 1854, which made tall office and apartment buildings practical.[6] Another important technology for the new architecture was electric light, which greatly reduced the inherent danger of fires caused by gas in the 19th century.[7]

The debut of new materials and techniques inspired architects to break away from the neoclassical and eclectic models that dominated European and American architecture in the late 19th century, most notably eclecticism, Victorian and Edwardian architecture, and the Beaux-Arts architectural style.[8] This break with the past was particularly urged by the architectural theorist and historian Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. In his 1872 book Entretiens sur L'Architecture, he urged: "use the means and knowledge given to us by our times, without the intervening traditions which are no longer viable today, and in that way we can inaugurate a new architecture. For each function its material; for each material its form and its ornament."[9] This book influenced a generation of architects, including Louis Sullivan, Victor Horta, Hector Guimard, and Antoni Gaudí.[10]

At the end of the 19th century, a few architects began to challenge the traditional Beaux Arts and Neoclassical styles that dominated architecture in Europe and the United States. The Glasgow School of Art (1896–99) designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh, had a façade dominated by large vertical bays of windows.[11] The Art Nouveau style was launched in the 1890s by Victor Horta in Belgium and Hector Guimard in France; it introduced new styles of decoration, based on vegetal and floral forms. In Barcelona, Antonio Gaudi conceived architecture as a form of sculpture; the façade of the Casa Batlló in Barcelona (1904–1907) had no straight lines; it was encrusted with colorful mosaics of stone and ceramic tiles.[12]

Architects also began to experiment with new materials and techniques, which gave them greater freedom to create new forms. In 1903–1904 in Paris Auguste Perret and Henri Sauvage began to use reinforced concrete, previously only used for industrial structures, to build apartment buildings.[13] Reinforced concrete, which could be molded into any shape, and which could create enormous spaces without the need of supporting pillars, replaced stone and brick as the primary material for modernist architects. The first concrete apartment buildings by Perret and Sauvage were covered with ceramic tiles, but in 1905 Perret built the first concrete parking garage on 51 rue de Ponthieu in Paris; here the concrete was left bare, and the space between the concrete was filled with glass windows. Henri Sauvage added another construction innovation in an apartment building on Rue Vavin in Paris (1912–1914); the reinforced concrete building was in steps, with each floor set back from the floor below, creating a series of terraces. Between 1910 and 1913, Auguste Perret built the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, a masterpiece of reinforced concrete construction, with Art Deco sculptural bas-reliefs on the façade by Antoine Bourdelle. Because of the concrete construction, no columns blocked the spectator's view of the stage.[14]

Otto Wagner, in Vienna, was another pioneer of the new style. In his book Moderne Architektur (1895) he had called for a more rationalist style of architecture, based on "modern life".[15] He designed a stylized ornamental metro station at Karlsplatz in Vienna (1888–89), then an ornamental Art Nouveau residence, Majolika House (1898), before moving to a much more geometric and simplified style, without ornament, in the Austrian Postal Savings Bank (1904–1906). Wagner declared his intention to express the function of the building in its exterior. The reinforced concrete exterior was covered with plaques of marble attached with bolts of polished aluminum. The interior was purely functional and spare, a large open space of steel, glass, and concrete where the only decoration was the structure itself.[16]

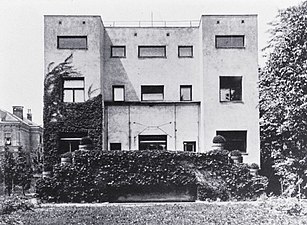

The Viennese architect Adolf Loos also began removing any ornament from his buildings. His Steiner House, in Vienna (1910), was an example of what he called rationalist architecture; it had a simple stucco rectangular façade with square windows and no ornament. The fame of the new movement, which became known as the Vienna Secession spread beyond Austria. Josef Hoffmann, a student of Wagner, constructed a landmark of early modernist architecture, the Palais Stoclet, in Brussels, in 1906–1911. This residence, built of brick covered with Norwegian marble, was composed of geometric blocks, wings, and a tower. A large pool in front of the house reflected its cubic forms. The interior was decorated with paintings by Gustav Klimt and other artists, and the architect even designed clothing for the family to match the architecture.[17]

In Germany, a modernist industrial movement, Deutscher Werkbund (German Work Federation) had been created in Munich in 1907 by Hermann Muthesius, a prominent architectural commentator. Its goal was to bring together designers and industrialists, to turn out well-designed, high-quality products, and in the process to invent a new type of architecture.[18] The organization originally included twelve architects and twelve business firms, but quickly expanded. The architects include Peter Behrens, Theodor Fischer (who served as its first president), Josef Hoffmann and Richard Riemerschmid.[19] In 1909 Behrens designed one of the earliest and most influential industrial buildings in the modernist style, the AEG turbine factory, a functional monument of steel and concrete. In 1911–1913, Adolf Meyer and Walter Gropius, who had both worked for Behrens, built another revolutionary industrial plant, the Fagus Factory in Alfeld an der Laine, a building without ornament where every construction element was on display. The Werkbund organized a major exposition of modernist design in Cologne just a few weeks before the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. For the 1914 Cologne exhibition, Bruno Taut built a revolutionary glass pavilion.[20]

During the 1920s and 1930s, Frank Lloyd Wright resolutely refused to associate himself with any architectural movements. He considered his architecture to be entirely unique and his own. Between 1916 and 1922, he broke away from his earlier prairie house style and worked instead on houses decorated with textured blocks of cement; this became known as his "Mayan style", after the pyramids of the ancient Mayan civilization. He experimented for a time with modular mass-produced housing. He identified his architecture as "Usonian", a combination of USA, "utopian" and "organic social order". His business was severely affected by the beginning of the Great Depression that began in 1929; he had fewer wealthy clients who wanted to experiment. Between 1928 and 1935, he built only two buildings: a hotel near Chandler, Arizona, and the most famous of all his residences, Fallingwater (1934–37), a vacation house in Pennsylvania for Edgar J. Kaufman. Fallingwater is a remarkable structure of concrete slabs suspended over a waterfall, perfectly uniting architecture and nature.[41]

The Austrian architect Rudolph Schindler designed what could be called the first house in the modern style in 1922, the Schindler house.

Schindler also contributed to American modernism with his design for the Lovell Beach House in Newport Beach. The Austrian architect Richard Neutra moved to the United States in 1923, worked for a short time with Frank Lloyd Wright, also quickly became a force in American architecture through his modernist design for the same client, the Lovell Health House in Los Angeles. Neutra's most notable architectural work was the Kaufmann Desert House in 1946, and he designed hundreds of further projects.[42]

The 1937 Paris International Exposition in Paris effectively marked the end of the Art Deco, and of pre-war architectural styles. Most of the pavilions were in a neoclassical Deco style, with colonnades and sculptural decoration. The pavilions of Nazi Germany, designed by Albert Speer, in a German neoclassical style topped by eagle and swastika, faced the pavilion of the Soviet Union, topped by enormous statues of a worker and a peasant carrying a hammer and sickle. As to the modernists, Le Corbusier was practically, but not quite invisible at the Exposition; he participated in the Pavilion des temps nouveaux, but focused mainly on his painting.[43] The one modernist who did attract attention was a collaborator of Le Corbusier, Josep Lluis Sert, the Spanish architect, whose pavilion of the Second Spanish Republic was pure modernist glass and steel box. Inside it displayed the most modernist work of the Exposition, the painting Guernica by Pablo Picasso. The original building was destroyed after the Exposition, but it was recreated in 1992 in Barcelona.

The rise of nationalism in the 1930s was reflected in the Fascist architecture of Italy, and Nazi architecture of Germany, based on classical styles and designed to express power and grandeur. The Nazi architecture, much of it designed by Albert Speer, was intended to awe the spectators by its huge scale. Adolf Hitler intended to turn Berlin into the capital of Europe, grander than Rome or Paris. The Nazis closed the Bauhaus, and the most prominent modern architects soon departed for Britain or the United States. In Italy, Benito Mussolini wished to present himself as the heir to the glory and empire of ancient Rome.[44] Mussolini's government was not as hostile to modernism as The Nazis; the spirit of Italian Rationalism of the 1920s continued, with the work of architect Giuseppe Terragni. His Casa del Fascio in Como, headquarters of the local Fascist party, was a perfectly modernist building, with geometric proportions (33.2 meters long by 16.6 meters high), a clean façade of marble, and a Renaissance-inspired interior courtyard. Opposed to Terragni was Marcello Piacitini, a proponent of monumental fascist architecture, who rebuilt the University of Rome, and designed the Italian pavilion at the 1937 Paris Exposition, and planned a grand reconstruction of Rome on the fascist model.[45]

The 1939 New York World's Fair marked a turning point in architecture between Art Deco and modern architecture. The theme of the Fair was the World of Tomorrow, and its symbols were the purely geometric trylon and periphery sculpture. It had many monuments to Art Deco, such as the Ford Pavilion in the Streamline Moderne style, but also included the new International Style that would replace Art Deco as the dominant style after the War. The Pavilions of Finland, by Alvar Aalto, of Sweden by Sven Markelius, and of Brazil by Oscar Niemeyer and Lúcio Costa, looked forward to a new style. They became leaders in the postwar modernist movement.[46]

World War II (1939–1945) and its aftermath was a major factor in driving innovation in building technology, and in turn, architectural possibilities.[40][47] The wartime industrial demands resulted in shortages of steel and other building materials, leading to the adoption of new materials, such as aluminum, The war and postwar period brought greatly expanded use of prefabricated building; largely for the military and government. The semi-circular metal Nissen hut of World War I was revived as the Quonset hut. The years immediately after the war saw the development of radical experimental houses, including the enameled-steel Lustron house (1947–1950), and Buckminster Fuller's experimental aluminum Dymaxion House.[47][48]

The unprecedented destruction caused by the war was another factor in the rise of modern architecture. Large parts of major cities, from Berlin, Tokyo, and Dresden to Rotterdam and east London; all the port cities of France, particularly Le Havre, Brest, Marseille, Cherbourg had been destroyed by bombing. In the United States, little civilian construction had been done since the 1920s; housing was needed for millions of American soldiers returning from the war. The postwar housing shortages in Europe and the United States led to the design and construction of enormous government-financed housing projects, usually in run-down center of American cities, and in the suburbs of Paris and other European cities, where land was available,

One of the largest reconstruction projects was that of the city center of Le Havre, destroyed by the Germans and by Allied bombing in 1944; 133 hectares of buildings in the center were flattened, destroying 12,500 buildings and leaving 40,000 persons homeless. The architect Auguste Perret, a pioneer in the use of reinforced concrete and prefabricated materials, designed and built an entirely new center to the city, with apartment blocks, cultural, commercial, and government buildings. He restored historic monuments when possible, and built a new church, St. Joseph, with a lighthouse-like tower in the center to inspire hope. His rebuilt city was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2005.[49]

Shortly after the War, the French architect Le Corbusier, who was nearly sixty years old and had not constructed a building in ten years, was commissioned by the French government to construct a new apartment block in Marseille. He called it Unité d'Habitation in Marseille, but it more popularly took the name of the Cité Radieuse (and later "Cité du Fada" "City of the crazy one" in Marseille French), after his book about futuristic urban planning. Following his doctrines of design, the building had a concrete frame raised up above the street on pylons. It contained 337 duplex apartment units, fit into the framework like pieces of a puzzle. Each unit had two levels and a small terrace. Interior "streets" had shops, a nursery school, and other serves, and the flat terrace roof had a running track, ventilation ducts, and a small theater. Le Corbusier designed furniture, carpets, and lamps to go with the building, all purely functional; the only decoration was a choice of interior colors that Le Corbusier gave to residents. Unité d'Habitation became a prototype for similar buildings in other cities, both in France and Germany. Combined with his equally radical organic design for the Chapel of Notre-Dame du-Haut at Ronchamp, this work propelled Corbusier in the first rank of postwar modern architects.[50]

In France, Le Corbusier remained the most prominent architect, though he built few buildings there. His most prominent late work was the convent of Sainte Marie de La Tourette in Evreaux-sur-l'Arbresle. The Convent, built of raw concrete, was austere and without ornament, inspired by the medieval monasteries he had visited on his first trip to Italy.[80]

In Britain, the major figures in modernism included Wells Coates (1895–1958), FRS Yorke (1906–1962), James Stirling (1926–1992) and Denys Lasdun (1914–2001). Lasdun's best-known work is the Royal National Theatre (1967–1976) on the south bank of the Thames. Its raw concrete and blockish form offended British traditionalists; Charles III, King of the U.K compared it with a nuclear power station.

In Belgium, a major figure was Charles Vandenhove (born 1927) who constructed an important series of buildings for the University Hospital Center in Liège. His later work ventured into colorful rethinking of historical styles, such as Palladian architecture.[81]

In Finland, the most influential architect was Alvar Aalto, who adapted his version of modernism to the Nordic landscape, light, and materials, particularly the use of wood. After World War II, he taught architecture in the United States. In Denmark, Arne Jacobsen was the best-known of the modernists, who designed furniture as well as carefully proportioned buildings.

In Italy, the most prominent modernist was Gio Ponti, who worked often with the structural engineer Pier Luigi Nervi, a specialist in reinforced concrete. Nervi created concrete beams of exceptional length, twenty-five meters, which allowed greater flexibility in forms and greater heights. Their best-known design was the Pirelli Building in Milan (1958–1960), which for decades was the tallest building in Italy.[82]

The most famous Spanish modernist was the Catalan architect Josep Lluis Sert, who worked with great success in Spain, France, and the United States. In his early career, he worked for a time under Le Corbusier, and designed the Spanish pavilion for the 1937 Paris Exposition. His notable later work included the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Provence, France (1964), and the Harvard Science Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He served as Dean of Architecture at the Harvard School of Design.

Notable German modernists included Johannes Krahn, who played an important part in rebuilding German cities after World War II, and built several important museums and churches, notably St. Martin, Idstein, which artfully combined stone masonry, concrete, and glass. Leading Austrian architects of the style included Gustav Peichl, whose later works included the Art and Exhibition Center of the German Federal Republic in Bonn, Germany (1989).

Tropical Modernism[edit]

Tropical Modernism, or Tropical Modern is a style of architecture that merges modernist architecture principles with tropical vernacular traditions, emerging in the mid-20th century. The term is used to describe modernist architecture in various regions of the world, including Latin America, Asia and Africa, as detailed below. Architects adapted to local conditions by using features which encouraged protection from harsh sunlight (such as solar shading) and encouraged the flow of cooling breezes through buildings (through narrow corridors).[83] Some contend that the style originated in the 'hot, humid conditions' of West Africa in the 1940s.[84] Typical features include geometric screens. Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, of the Architectural Association architecture school in London, UK, made important contributions to research and practice in the Tropical Modernism style, after founding the School of Tropical Study at the AA. Speaking about the adoption of modernism in post-independence Ghana, Professor Ola Ukuku, states that ‘those involved in developing Tropical Modernism were actually operating as agents of the colonies at the time’.[85]

Architectural historians sometimes label Latin American modernism as "tropical modernism". This reflects architects who adapted modernism to the tropical climate as well as the sociopolitical contexts of Latin America.[86]

Brazil became a showcase of modern architecture in the late 1930s through the work of Lúcio Costa (1902–1998) and Oscar Niemeyer (1907–2012). Costa had the lead and Niemeyer collaborated on the Ministry of Education and Health in Rio de Janeiro (1936–43) and the Brazilian pavilion at the 1939 World's Fair in New York. Following the war, Niemeyer, along with Le Corbusier, conceived the form of the United Nations Headquarters constructed by Walter Harrison.

Lúcio Costa also had overall responsibility for the plan of the most audacious modernist project in Brazil; the creation of new capital, Brasília, constructed between 1956 and 1961. Costa made the general plan, laid out in the form of a cross, with the major government buildings in the center. Niemeyer was responsible for designing the government buildings, including the palace of the President;the National Assembly, composed of two towers for the two branches of the legislature and two meeting halls, one with a cupola and other with an inverted cupola. Niemeyer also built the cathedral, eighteen ministries, and giant blocks of housing, each designed for three thousand residents, each with its own school, shops, and chapel. Modernism was employed both as an architectural principle and as a guideline for organizing society, as explored in The Modernist City.[87]

Following a military coup d'état in Brazil in 1964, Niemeyer moved to France, where he designed the modernist headquarters of the French Communist Party in Paris (1965–1980), a miniature of his United Nations plan.[88]

Mexico also had a prominent modernist movement. Important figures included Félix Candela, born in Spain, who emigrated to Mexico in 1939; he specialized in concrete structures in unusual parabolic forms. Another important figure was Mario Pani, who designed the National Conservatory of Music in Mexico City (1949), and the Torre Insignia (1988); Pani was also instrumental in the construction of the new University of Mexico City in the 1950s, alongside Juan O'Gorman, Eugenio Peschard, and Enrique del Moral. The Torre Latinoamericana, designed by Augusto H. Alvarez, was one of the earliest modernist skyscrapers in Mexico City (1956); it successfully withstood the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, which destroyed many other buildings in the city center. Pedro Ramirez Vasquez and Rafael Mijares designed the Olympic Stadium for the 1968 Olympics, and Antoni Peyri and Candela designed the Palace of Sports. Luis Barragan was another influential figure in Mexican modernism; his raw concrete residence and studio in Mexico City looks like a blockhouse on the outside, while inside it features great simplicity in form, pure colors, abundant natural light, and, one of is signatures, a stairway without a railing. He won the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1980, and the house was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2004.[89]

Japan, like Europe, had an enormous shortage of housing after the war, due to the bombing of many cities. 4.2 million housing units needed to be replaced. Japanese architects combined both traditional and modern styles and techniques. One of the foremost Japanese modernists was Kunio Maekawa (1905–1986), who had worked for Le Corbusier in Paris until 1930. His own house in Tokyo was an early landmark of Japanese modernism, combining traditional style with ideas he acquired working with Le Corbusier. His notable buildings include concert halls in Tokyo and Kyoto and the International House of Japan in Tokyo, all in the pure modernist style.

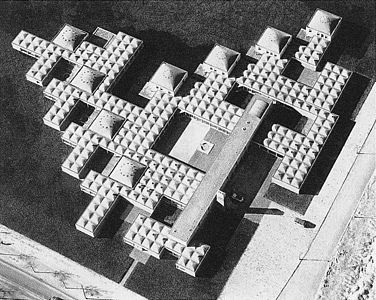

Kenzo Tange (1913–2005) worked in the studio of Kunio Maekawa from 1938 until 1945 before opening his own architectural firm. His first major commission was the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum . He designed many notable office buildings and cultural centers. office buildings, as well as the Yoyogi National Gymnasium for the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. The gymnasium, built of concrete, features a roof suspended over the stadium on steel cables.

The Danish architect Jørn Utzon (1918–2008) worked briefly with Alvar Aalto, studied the work of Le Corbusier, and traveled to the United States to meet Frank Lloyd Wright. In 1957 he designed one of the most recognizable modernist buildings in the world; the Sydney Opera House. He is known for the sculptural qualities of his buildings, and their relationship with the landscape. The five concrete shells of the structure resemble seashells by the beach. Begun in 1957, the project encountered considerable technical difficulties making the shells and getting the acoustics right. Utzon resigned in 1966, and the opera house was not finished until 1973, ten years after its scheduled completion.[90]

In India, modernist architecture was promoted by the postcolonial state under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, most notably by inviting Le Corbusier to design the city of Chandigarh.[91] Although Nehru advocated for young Indians to be part of Le Corbuiser's design team in order to refine their skills whilst building their city, the team included only one female Indian architect, Eulie Chowdhury.[91] Important Indian modernist architects also include BV Doshi, Charles Correa, Raj Rewal, Achyut Kanvinde, and Habib Rahman. Much discussion around modernist architecture took place in the journal MARG. In Sri Lanka, Geoffrey Bawa pioneered Tropical Modernism.[92] Minnette De Silva was an important Sri Lankan modernist architect.

Post independence architecture in Pakistan is a blend of Islamic and modern styles of architecture with influences from Mughal, indo-Islamic and international architectural designs. The 1960s and 1970s was a period of architectural Significance. Jinnah's Mausoleum, Minar e Pakistan, Bab e Khyber, Islamic summit minar and the Faisal mosque date from this time.

Modernist architecture in Ghana is also considered part of Tropical Modernism.[93][94]

Some notable modernist architects in Morocco were Elie Azagury and Jean-François Zevaco.[51]

Asmara, capitol of Eritrea, is well known for its modernist architecture dating from the period of Italian colonization.[95][96]

Preservation[edit]

Several works or collections of modern architecture have been designated by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. In addition to the early experiments associated with Art Nouveau, these include a number of the structures mentioned above in this article: the Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht, the Bauhaus structures in Weimar, Dessau, and Bernau, the Berlin Modernism Housing Estates, the White City of Tel Aviv, the city of Asmara, the city of Brasília, the Ciudad Universitaria of UNAM in Mexico City and the University City of Caracas in Venezuela, the Sydney Opera House, and the Centennial Hall in Wrocław, along with select works from Le Corbursier and Frank Lloyd Wright.

Private organizations such as Docomomo International, the World Monuments Fund, and the Recent Past Preservation Network are working to safeguard and document imperiled Modern architecture. In 2006, the World Monuments Fund launched Modernism at Risk, an advocacy and conservation program. The organization MAMMA. is working to document and preserve modernist architecture in Morocco.[97]