Ancient Greek art

Ancient Greek art stands out among that of other ancient cultures for its development of naturalistic but idealized depictions of the human body, in which largely nude male figures were generally the focus of innovation. The rate of stylistic development between about 750 and 300 BC was remarkable by ancient standards, and in surviving works is best seen in sculpture. There were important innovations in painting, which have to be essentially reconstructed due to the lack of original survivals of quality, other than the distinct field of painted pottery.

Greek architecture, technically very simple, established a harmonious style with numerous detailed conventions that were largely adopted by Roman architecture and are still followed in some modern buildings. It used a vocabulary of ornament that was shared with pottery, metalwork and other media, and had an enormous influence on Eurasian art, especially after Buddhism carried it beyond the expanded Greek world created by Alexander the Great. The social context of Greek art included radical political developments and a great increase in prosperity; the equally impressive Greek achievements in philosophy, literature and other fields are well known.

The earliest art by Greeks is generally excluded from "ancient Greek art", and instead known as Greek Neolithic art followed by Aegean art; the latter includes Cycladic art and the art of the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures from the Greek Bronze Age.[1] The art of ancient Greece is usually divided stylistically into four periods: the Geometric, Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic. The Geometric age is usually dated from about 1000 BC, although in reality little is known about art in Greece during the preceding 200 years, traditionally known as the Greek Dark Ages. The 7th century BC witnessed the slow development of the Archaic style as exemplified by the black-figure style of vase painting. Around 500 BC, shortly before the onset of the Persian Wars (480 BC to 448 BC), is usually taken as the dividing line between the Archaic and the Classical periods, and the reign of Alexander the Great (336 BC to 323 BC) is taken as separating the Classical from the Hellenistic periods. From some point in the 1st century BC onwards "Greco-Roman" is used, or more local terms for the Eastern Greek world.[2]

In reality, there was no sharp transition from one period to another. Forms of art developed at different speeds in different parts of the Greek world, and as in any age some artists worked in more innovative styles than others. Strong local traditions, and the requirements of local cults, enable historians to locate the origins even of works of art found far from their place of origin. Greek art of various kinds was widely exported. The whole period saw a generally steady increase in prosperity and trading links within the Greek world and with neighbouring cultures.

The survival rate of Greek art differs starkly between media. We have huge quantities of pottery and coins, much stone sculpture, though even more Roman copies, and a few large bronze sculptures. Almost entirely missing are painting, fine metal vessels, and anything in perishable materials including wood. The stone shell of a number of temples and theatres has survived, but little of their extensive decoration.[3]

Fine metalwork was an important art in ancient Greece, but later production is very poorly represented by survivals, most of which come from the edges of the Greek world or beyond, from as far as France or Russia. Vessels and jewellery were produced to high standards, and exported far afield. Objects in silver, at the time worth more relative to gold than it is in modern times, were often inscribed by the maker with their weight, as they were treated largely as stores of value, and likely to be sold or re-melted before very long.[22]

During the Geometric and Archaic phases, the production of large metal vessels was an important expression of Greek creativity, and an important stage in the development of bronzeworking techniques, such as casting and repousse hammering. Early sanctuaries, especially Olympia, yielded many hundreds of tripod-bowl or sacrificial tripod vessels, mostly in bronze, deposited as votives. These had a shallow bowl with two handles raised high on three legs; in later versions the stand and bowl were different pieces. During the Orientalising period, such tripods were frequently decorated with figural protomes, in the shape of griffins, sphinxes and other fantastic creatures.[23]

Swords, the Greek helmet and often body armour such as the muscle cuirass were made of bronze, sometimes decorated in precious metal, as in the 3rd-century Ksour Essef cuirass.[24] Armour and "shield-bands" are two of the contexts for strips of Archaic low relief scenes, which were also attached to various objects in wood; the band on the Vix Krater is a large example.[25] Polished bronze mirrors, initially with decorated backs and kore handles, were another common item; the later "folding mirror" type had hinged cover pieces, often decorated with a relief scene, typically erotic.[26] Coins are described below.

From the late Archaic the best metalworking kept pace with stylistic developments in sculpture and the other arts, and Phidias is among the sculptors known to have practiced it.[27] Hellenistic taste encouraged highly intricate displays of technical virtuousity, tending to "cleverness, whimsy, or excessive elegance".[28] Many or most Greek pottery shapes were taken from shapes first used in metal, and in recent decades there has been an increasing view that much of the finest vase-painting reused designs by silversmiths for vessels with engraving and sections plated in a different metal, working from drawn designs.[29]

Exceptional survivals of what may have been a relatively common class of large bronze vessels are two volute kraters, for mixing wine and water.[30] These are the Vix Krater, c. 530 BC, 1.63m (5'4") high and over 200 kg (450 lbs) in weight, holding some 1,100 litres, and found in the burial of a Celtic woman in modern France,[31] and the 4th-century Derveni Krater, 90.5 cm (35 in.) high.[32] The elites of other neighbours of the Greeks, such as the Thracians and Scythians, were keen consumers of Greek metalwork, and probably served by Greek goldsmiths settled in their territories, who adapted their products to suit local taste and functions. Such hybrid pieces form a large part of survivals, including the Panagyurishte Treasure, Borovo Treasure, and other Thracian treasures, and several Scythian burials, which probably contained work by Greek artists based in the Greek settlements on the Black Sea.[33] As with other luxury arts, the Macedonian royal cemetery at Vergina has produced objects of top quality from the cusp of the Classical and Hellenistic periods.[34]

Jewellery for the Greek market is often of superb quality,[35] with one unusual form being intricate and very delicate gold wreaths imitating plant-forms, worn on the head. These were probably rarely, if ever, worn in life, but were given as votives and worn in death.[36] Many of the Fayum mummy portraits wear them. Some pieces, especially in the Hellenistic period, are large enough to offer scope for figures, as did the Scythian taste for relatively substantial pieces in gold.[37]

Architecture (meaning buildings executed to an aesthetically considered design) ceased in Greece from the end of the Mycenaean period (about 1200 BC) until the 7th century, when urban life and prosperity recovered to a point where public building could be undertaken. Since most Greek buildings in the Archaic and Early Classical periods were made of wood or mudbrick, nothing remains of them except a few ground-plans, and there are almost no written sources on early architecture or descriptions of buildings. Most of our knowledge of Greek architecture comes from the surviving buildings of the Late Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods (since ancient Roman architecture heavily used Greek styles), and from late written sources such as Vitruvius (1st century BC). This means that there is a strong bias towards temples, the most common major buildings to survive. Here the squared blocks of stone used for walls were useful for later buildings, and so often all that survives are parts of columns and metopes that were harder to recycle.[77]

For most of the period a strict stone post and lintel system of construction was used, held in place only by gravity. Corbelling was known in Mycenean Greece, and the arch was known from the 5th century at the latest, but hardly any use was made of these techniques until the Roman period.[78] Wood was only used for ceilings and roof timbers in prestigious stone buildings. The use of large terracotta roof tiles, only held in place by grooving, meant that roofs needed to have a low pitch.[79]

Until Hellenistic times only public buildings were built using the formal stone style; these included above all temples, and the smaller treasury buildings which often accompanied them, and were built at Delphi by many cities. Other building types, often not roofed, were the central agora, often with one or more colonnaded stoa around it, theatres, the gymnasium and palaestra or wrestling-school, the ekklesiasterion or bouleuterion for assemblies, and the propylaea or monumental gateways.[80] Round buildings for various functions were called a tholos,[81] and the largest stone structures were often defensive city walls.

Tombs were for most of the period only made as elaborate mausolea around the edges of the Greek world, especially in Anatolia.[82] Private houses were built around a courtyard where funds allowed, and showed blank walls to the street. They sometimes had a second story, but very rarely basements. They were usually built of rubble at best, and relatively little is known about them; at least for males, much of life was spent outside them.[83] A few palaces from the Hellenistic period have been excavated.[84]

Temples and some other buildings such as the treasuries at Delphi were planned as either a cube or, more often, a rectangle made from limestone, of which Greece has an abundance, and which was cut into large blocks and dressed. This was supplemented by columns, at least on the entrance front, and often on all sides.[85] Other buildings were more flexible in plan, and even the wealthiest houses seem to have lacked much external ornament. Marble was an expensive building material in Greece: high quality marble came only from Mt Pentelus in Attica and from a few islands such as Paros, and its transportation in large blocks was difficult. It was used mainly for sculptural decoration, not structurally, except in the very grandest buildings of the Classical period such as the Parthenon in Athens.[86]

There were two main classical orders of Greek architecture, the Doric and the Ionic, with the Corinthian order only appearing in the Classical period, and not becoming dominant until the Roman period. The most obvious features of the three orders are the capitals of the columns, but there are significant differences in other points of design and decoration between the orders.[87] These names were used by the Greeks themselves, and reflected their belief that the styles descended from the Dorian and Ionian Greeks of the Dark Ages, but this is unlikely to be true. The Doric was the earliest, probably first appearing in stone in the earlier 7th century, having developed (though perhaps not very directly) from predecessors in wood.[88] It was used in mainland Greece and the Greek colonies in Italy. The Ionic style was first used in the cities of Ionia (now the west coast of Turkey) and some of the Aegean islands, probably beginning in the 6th century.[89] The Doric style was more formal and austere, the Ionic more relaxed and decorative. The more ornate Corinthian order was a later development of the Ionic, initially apparently only used inside buildings, and using Ionic forms for everything except the capitals. The famous and well-preserved Choragic Monument of Lysicrates near the Acropolis of Athens (335/334) is the first known use of the Corinthian order on the exterior of a building.[90]

Most of the best known surviving Greek buildings, such as the Parthenon and the Temple of Hephaestus in Athens, are Doric. The Erechtheum, next to the Parthenon, however, is Ionic. The Ionic order became dominant in the Hellenistic period, since its more decorative style suited the aesthetic of the period better than the more restrained Doric. Some of the best surviving Hellenistic buildings, such as the Library of Celsus, can be seen in Turkey, at cities such as Ephesus and Pergamum.[91] But in the greatest of Hellenistic cities, Alexandria in Egypt, almost nothing survives.

Coins were (probably) invented in Lydia in the 7th century BC, but they were first extensively used by the Greeks,[93] and the Greeks set the canon of coin design which has been followed ever since. Coin design today still recognisably follows patterns descended from ancient Greece. The Greeks did not see coin design as a major art form, although some were expensively designed by leading goldsmiths, especially outside Greece itself, among the Central Asian kingdoms and in Sicilian cities keen to promote themselves. Nevertheless, the durability and abundance of coins have made them one of the most important sources of knowledge about Greek aesthetics.[94] Greek coins are the only art form from the ancient Greek world which can still be bought and owned by private collectors of modest means.

The most widespread coins, used far beyond their native territories and copied and forged by others, were the Athenian tetradrachm, issued from c. 510 to c. 38 BC, and in the Hellenistic age the Macedonian tetradrachm, both silver.[95] These both kept the same familiar design for long periods.[96] Greek designers began the practice of putting a profile portrait on the obverse of coins. This was initially a symbolic portrait of the patron god or goddess of the city issuing the coin: Athena for Athens, Apollo at Corinth, Demeter at Thebes and so on. Later, heads of heroes of Greek mythology were used, such as Heracles on the coins of Alexander the Great.

The first human portraits on coins were those of Achaemenid Empire Satraps in Asia Minor, starting with the exiled Athenian general Themistocles who became a Satrap of Magnesia c. 450 BC, and continuing especially with the dynasts of Lycia towards the end of the 5th century.[97] Greek cities in Italy such as Syracuse began to put the heads of real people on coins in the 4th century BC, as did the Hellenistic successors of Alexander the Great in Egypt, Syria and elsewhere.[98] On the reverse of their coins the Greek cities often put a symbol of the city: an owl for Athens, a dolphin for Syracuse and so on. The placing of inscriptions on coins also began in Greek times. All these customs were later continued by the Romans.[94]

The most artistically ambitious coins, designed by goldsmiths or gem-engravers, were often from the edges of the Greek world, from new colonies in the early period and new kingdoms later, as a form of marketing their "brands" in modern terms.[99] Of the larger cities, Corinth and Syracuse also issued consistently attractive coins. Some of the Greco-Bactrian coins are considered the finest examples of Greek coins with large portraits with "a nice blend of realism and idealization", including the largest coins to be minted in the Hellenistic world: the largest gold coin was minted by Eucratides (reigned 171–145 BC), the largest silver coin by the Indo-Greek king Amyntas Nikator (reigned c. 95–90 BC). The portraits "show a degree of individuality never matched by the often bland depictions of their royal contemporaries further West".[100]

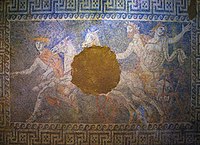

Mosaics were initially made with rounded pebbles, and later glass with tesserae which gave more colour and a flat surface. They were popular in the Hellenistic period, at first as decoration for the floors of palaces, but eventually for private homes.[118] Often a central emblema picture in a central panel was completed in much finer work than the surrounding decoration.[119] Xenia motifs, where a house showed examples of the variety of foods guests might expect to enjoy, provide most of the surviving specimens of Greek still-life. In general mosaic must be considered as a secondary medium copying painting, often very directly, as in the Alexander Mosaic.[120]

The Unswept Floor by Sosus of Pergamon (c. 200 BC) was an original and famous trompe-l'œil piece, known from many Greco-Roman copies. According to John Boardman, Sosus is the only mosaic artist whose name has survived; his Doves are also mentioned in literature and copied.[121] However, Katherine M. D. Dunbabin asserts that two different mosaic artists left their signatures on mosaics of Delos.[122] The artist of the 4th-century BC Stag Hunt Mosaic perhaps also left his signature as Gnosis, although this word may be a reference to the abstract concept of knowledge.[123]

Mosaics are a significant element of surviving Macedonian art, with a large number of examples preserved in the ruins of Pella, the ancient Macedonian capital, in today's Central Macedonia.[124] Mosaics such as the "Stag Hunt Mosaic and Lion Hunt" mosaic demonstrate illusionist and three dimensional qualities generally found in Hellenistic paintings, although the rustic Macedonian pursuit of hunting is markedly more pronounced than other themes.[125] The 2nd-century-BC mosaics of Delos, Greece were judged by François Chamoux as representing the pinnacle of Hellenistic mosaic art, with similar styles that continued throughout the Roman period and perhaps laid the foundations for the widespread use of mosaics in the Western world through to the Middle Ages.[118]

Historiography[edit]

The Hellenized Roman upper classes of the Late Republic and Early Empire generally accepted Greek superiority in the arts without many quibbles, though the praise of Pliny for the sculpture and painting of pre-Hellenistic artists may be based on earlier Greek writings rather than much personal knowledge. Pliny and other classical authors were known in the Renaissance, and this assumption of Greek superiority was again generally accepted. However critics in the Renaissance and much later were unclear which works were actually Greek.[149]

As a part of the Ottoman Empire, Greece itself could only be reached by a very few western Europeans until the mid-18th century. Not only the Greek vases found in the Etruscan cemeteries, but also (more controversially) the Greek temples of Paestum were taken to be Etruscan, or otherwise Italic, until the late 18th century and beyond, a misconception prolonged by Italian nationalist sentiment.[149]

The writings of Johann Joachim Winckelmann, especially his books Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1750) and Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums ("History of Ancient Art", 1764) were the first to distinguish sharply between ancient Greek, Etruscan, and Roman art, and define periods within Greek art, tracing a trajectory from growth to maturity and then imitation or decadence that continues to have influence to the present day.[150]

The full disentangling of Greek statues from their later Roman copies, and a better understanding of the balance between Greekness and Roman-ness in Greco-Roman art was to take much longer, and perhaps still continues.[151] Greek art, especially sculpture, continued to enjoy an enormous reputation, and studying and copying it was a large part of the training of artists, until the downfall of Academic art in the late 19th century. During this period, the actual known corpus of Greek art, and to a lesser extent architecture, has greatly expanded. The study of vases developed an enormous literature in the late 19th and 20th centuries, much based on the identification of the hands of individual artists, with Sir John Beazley the leading figure. This literature generally assumed that vase-painting represented the development of an independent medium, only in general terms drawing from stylistic development in other artistic media. This assumption has been increasingly challenged in recent decades, and some scholars now see it as a secondary medium, largely representing cheap copies of now lost metalwork, and much of it made, not for ordinary use, but to deposit in burials.[152]

![Silver rhyton for the Thracian market, end 4th century[38]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Rhyton_Greek_Thracian_silver%2C_end_of_4th_c_BC%2C_Prague_Kinsky%2C_NM-HM10_1407%2C_140856.jpg/190px-Rhyton_Greek_Thracian_silver%2C_end_of_4th_c_BC%2C_Prague_Kinsky%2C_NM-HM10_1407%2C_140856.jpg)

![Model of the processional way at Ancient Delphi, without much of the statuary shown.[92]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/15/Santuario_Delfos.jpg/200px-Santuario_Delfos.jpg)

![A banquet scene from a Macedonian tomb of Agios Athanasios, Thessaloniki, 4th century BC; six men are shown reclining on couches, with food arranged on nearby tables, a male servant in attendance, and female musicians providing entertainment.[111]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c6/Banquet%2C_tombe_d%27Agios_Athanasios.jpg/200px-Banquet%2C_tombe_d%27Agios_Athanasios.jpg)

![The Sampul tapestry, a woollen wall hanging from Lop County, Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang, China, showing a possibly Greek soldier from the Greco-Bactrian kingdom (250–125 BC), with blue eyes, wielding a spear, and wearing what appears to be a diadem headband; depicted above him is a centaur, from Greek mythology, a common motif in Hellenistic art;[112] Xinjiang Region Museum.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/UrumqiWarrior.jpg/89px-UrumqiWarrior.jpg)

![Alexander the Great (left), wearing a kausia and fighting an Asiatic lion with his friend Craterus (detail); late 4th-century BC mosaic from Pella[126]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3d/Lion_hunt_mosaic_from_Pella.jpg/200px-Lion_hunt_mosaic_from_Pella.jpg)

![Hellenistic mosaic from Thmuis (Mendes), Egypt, signed by Sophilos c. 200 BC; Ptolemaic Queen Berenice II (joint ruler with her husband Ptolemy III) as the personification of Alexandria.[127]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/Mosaic_of_Berenice_II%2C_Ptolemaic_Queen_and_joint_ruler_with_Ptolemy_III_of_Egypt%2C_Thmuis%2C_Egypt.jpg/200px-Mosaic_of_Berenice_II%2C_Ptolemaic_Queen_and_joint_ruler_with_Ptolemy_III_of_Egypt%2C_Thmuis%2C_Egypt.jpg)