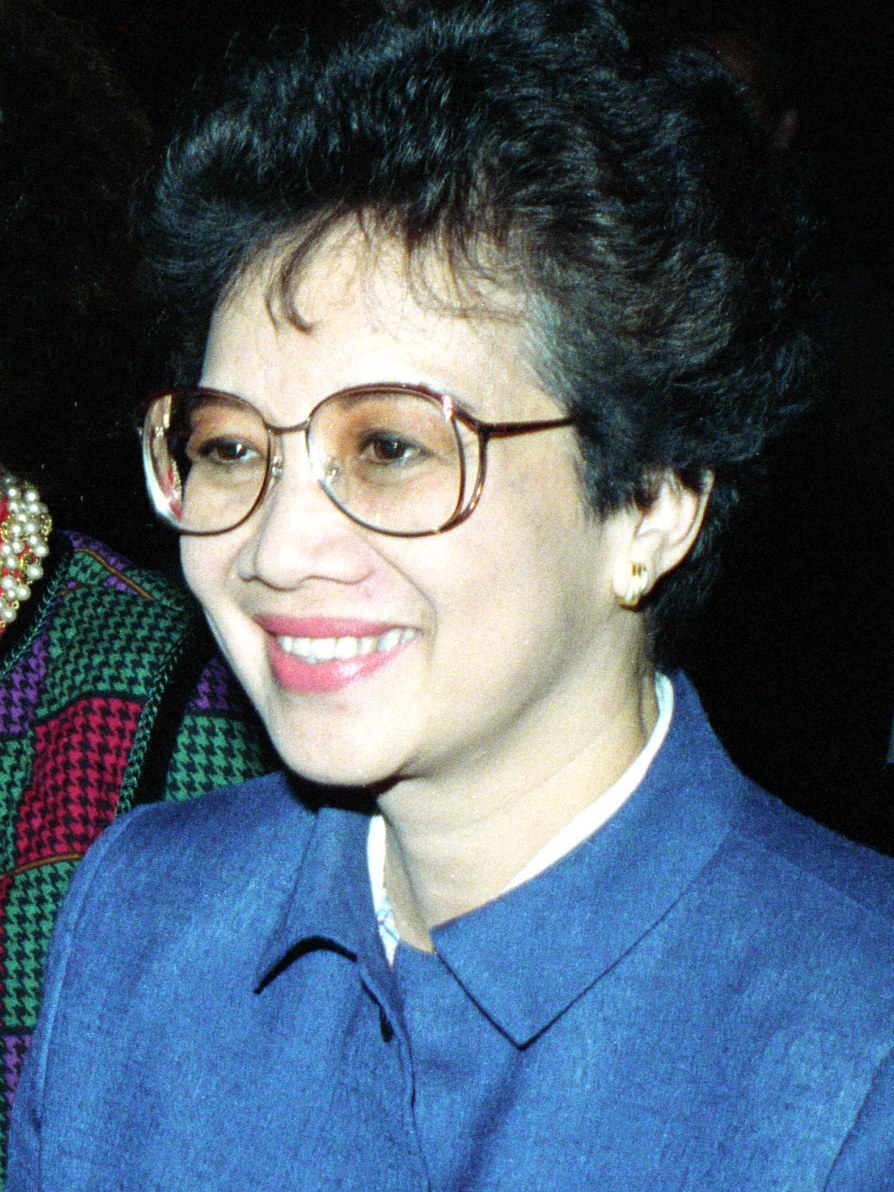

Corazon Aquino

Maria Corazon "Cory" Sumulong Cojuangco-Aquino[4] CCLH (Tagalog: [kɔɾaˈsɔn kɔˈhwaŋkɔ aˈkino]; January 25, 1933 – August 1, 2009) was a Filipino politician who served as the eleventh president of the Philippines from 1986 to 1992. She was the most prominent figure of the 1986 People Power Revolution, which ended the two-decade rule of President Ferdinand Marcos and led to the establishment of the current democratic Fifth Philippine Republic.

In this Philippine name for married women, the birth middle name or maternal family name is Sumulong, the birth surname or paternal family name is Cojuangco, and the marital name is Aquino.

Corazon C. Aquino

Salvador Laurel (Feb.–Mar. 1986)

August 1, 2009 (aged 76)

Makati, Philippines

Manila Memorial Park – Sucat, Parañaque, Philippines

PDP–Laban (1986–2009)

UNIDO (1986–88)

- Maria Elena Aquino-Cruz

- Aurora Corazon Aquino-Abellada

- Benigno Simeon Aquino III

- Victoria Elisa Aquino-Dee

- Kristina Bernadette Aquino

- José Cojuangco (father)

-

- Cojuangco family

- Aquino family

- Josephine C. Reyes (sister)

- Jose Cojuangco Jr. (brother)

- Juan Sumulong (grandfather)

- Lorenzo Sumulong (uncle)

- Victor Sumulong (first cousin)

- Jose W. Diokno (sixth cousin twice removed)[b]

College of Mount Saint Vincent (BA)

Far Eastern University (no degree)

Politician

Housewife

Activist

Cory

Corazon Aquino was married to Senator Benigno Aquino Jr., who was one of the most prominent critics of President Marcos. After the assassination of her husband on August 21, 1983, she emerged as leader of the opposition against the president. In late 1985, Marcos called for a snap election, and Aquino ran for president with former Senator Salvador Laurel as her running mate for vice president. After the election held on February 7, 1986, the Batasang Pambansa proclaimed Marcos and his running mate Arturo Tolentino as the winners, which prompted allegations of electoral fraud and Aquino's call for massive civil disobedience actions. Subsequently, the People Power Revolution, a non-violent mass demonstration movement, took place from February 22 to 25. The People Power Revolution, along with defections from the Armed Forces of the Philippines and support from the Philippine Catholic Church, ousted Marcos and secured Aquino's accession to the presidency on February 25, 1986. Prior to her election as president, Aquino had not held any elected office. She was the first female president of the Philippines.

As president, Aquino oversaw the drafting of the 1987 Constitution, which limited the powers of the presidency and re-established the bicameral Congress, removing the previous dictatorial government structure. Her economic policies focused on forging good economic standing amongst the international community as well as disestablishing Marcos-era crony capitalist monopolies, emphasizing the free market and responsible economy. Her administration pursued peace talks to resolve the Moro conflict, and the result of these talks was creation of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao. Aquino was criticized for the Mendiola Massacre, which resulted in the shooting deaths of at least 12 peaceful protesters by Philippine state security forces. The Philippines faced various natural calamities in the latter part of Aquino's administration, such as the 1990 Luzon earthquake, 1991 Mt. Pinatubo eruption and Tropical Storm Thelma. Several coup attempts were made against her government. She was succeeded as president by Fidel V. Ramos and returned to civilian life in 1992.

Aquino was diagnosed with colorectal cancer in 2008 and died on August 1, 2009. Her son Benigno Aquino III served as president of the Philippines from 2010 to 2016. After her death, monuments were built and public landmarks were named in honor of Corazon Aquino all around the Philippines. Aquino was regarded as the Mother of Democracy.[5][6][7][8]

Early life and education[edit]

María Corazón Sumulong Cojuangco was born on January 25, 1933, in Paniqui, Tarlac.[9] She was born to the prominent Cojuangco family. Her father was José Cojuangco, a prominent Tarlac businessman and former congressman, and her mother was Demetria Sumulong, a pharmacist. Both of Aquino's parents were from prominent political families. Aquino's grandfather from her father's side, Melecio Cojuangco, was a member of the historic Malolos Congress, and Aquino's mother belonged to the politically influential Sumulong family of Rizal province, which included Juan Sumulong, who ran against Commonwealth President Manuel L. Quezon in 1941 and Senator Lorenzo Sumulong, who was later appointed by Aquino in the Constitutional Commission. Aquino was the sixth of eight children, two of whom died in infancy. Her siblings were Pedro, Josephine, Teresita, Jose Jr., and Maria Paz.[10]

Aquino spent her elementary school days at St. Scholastica's College in Manila, where she graduated at the top of her class as valedictorian. She transferred to Assumption Convent to pursue high school studies. After her family moved to the United States, she attended the Assumption-run Ravenhill Academy in Philadelphia. She then transferred to Notre Dame Convent School in New York City, where she graduated from in 1949. During her high school years in the United States, Aquino volunteered for the campaign of U.S. Republican presidential candidate Thomas Dewey against Democratic incumbent U.S. President Harry S. Truman during the 1948 United States presidential election.[10] After graduating from high school, she pursued her college education at the College of Mount Saint Vincent in New York, graduating in 1953 with a major in French and minor in mathematics.

After graduating from college, she returned to the Philippines and studied law at Far Eastern University in 1953.[11] While attending, she met Benigno "Ninoy" S. Aquino Jr., who was the son of the late Speaker Benigno S. Aquino Sr. and a grandson of General Servillano Aquino. She discontinued her law education and married Benigno at the church of Our Lady of Sorrows in Pasay City on October 11, 1954.[12] The couple had five children: Maria Elena ("Ballsy"; born 1955), Aurora Corazon ("Pinky"; born 1957), Benigno Simeon III ("Noynoy"; 1960–2021), Victoria Elisa ("Viel"; born 1961) and Kristina Bernadette ("Kris"; born 1971).[13][14]

Aquino had initially had difficulty adjusting to provincial life when she and her husband moved to Concepcion, Tarlac, in 1955. Aquino found herself bored in Concepcion, and welcomed the opportunity to have dinner with her husband inside the American military facility at nearby Clark Field.[15] Afterwards, the Aquino family moved to a bungalow in suburban Quezon City.

Throughout her life, Aquino was known to be a devout Roman Catholic.[11]

Corazon Aquino was fluent in French, Japanese, Spanish, and English aside from her native Tagalog and Kapampangan.[11]

Wife of Benigno Aquino Jr.[edit]

Corazon Aquino's husband Benigno Aquino Jr., a member of the Liberal Party, rose to become the youngest governor in the country in 1961 and then the youngest senator ever elected to the Senate of the Philippines in 1967. For most of her husband's political career, Aquino remained a housewife who raised their children and hosted her spouse's political allies who would visit their Quezon City home.[16] She would decline to join her husband on stage during campaign rallies, instead preferring to be in the back of the audience and listen to him.[15] Unbeknownst to many at the time, Corazon Aquino sold some of her prized inheritance to fund the candidacy of her husband.

As Benigno Aquino Jr. emerged as a leading critic of the government of President Ferdinand Marcos, he became seen as a strong candidate for president to succeed Marcos in the 1973 elections. However, Marcos, who was barred by the 1935 Constitution to seek a third term, declared martial law on September 21, 1972 and later abolished the constitution, thereby allowing him to remain in office. Benigno Aquino Jr. was among the first to be arrested at the onset of martial law, and was later sentenced to death. During her husband's incarceration, Corazon Aquino stopped going to beauty salons or buying new clothes and prohibited her children from attending parties, until a priest advised her and her children to try to live as normal lives as possible.[15]

Despite Corazon's initial opposition, Benigno Aquino Jr. decided to run in the 1978 Batasang Pambansa elections from his prison cell as party leader of the newly created LABAN. Corazon Aquino campaigned on behalf of her husband and delivered a political speech for the first time in her life during this political campaign. In 1980 Benigno Aquino Jr. suffered a heart attack, and Marcos allowed Senator Aquino and his family to leave for exile in the United States upon intervention from U.S. President Jimmy Carter so that Aquino could seek medical treatment.[17][18] The family settled in Boston, and Corazon Aquino would later recall the next three years as the happiest days of her marriage and family life.

On August 21, 1983, Benigno Aquino Jr. ended his stay in the United States and returned without his family to the Philippines, where he was immediately assassinated on a staircase leading to the tarmac of Manila International Airport. The airport is now named Ninoy Aquino International Airport, renamed by the Congress in his honor in 1987. Corazon Aquino returned to the Philippines a few days later and led her husband's funeral procession, in which more than two million people participated.[17]

Presidential styles of

Corazon Aquino

In popular culture[edit]

In 2008, a musical play about Aquino entitled Cory, the Musical was staged at the Meralco Theater. It was written and directed by Nestor Torre Jr. and starred Isay Alvarez as Aquino. The musical featured a libretto of 19 original songs composed by Lourdes Pimentel, wife of Senator Aquilino Pimentel Jr.[108][109][110]

After her peaceful accession to the presidency and the ousting of President Marcos, Aquino was named Time magazine's Woman of the Year in 1986.[111] In August 1999, Aquino was chosen by Time as one of the 20 Most Influential Asians of the 20th century.[112] Time also cited her as one of 65 great Asian Heroes in November 2006.[113]

In 1994, Aquino was cited as one of 100 Women Who Shaped World History in a reference book written by Gail Meyer Rolka.[114]

In 1996, she received the J. William Fulbright Prize for International Understanding from the Fulbright Association.[115]

In 1998, she was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay Award in recognition of her role in peaceful revolution to attain democracy.[116]

Since her death in 2009, the legacy of Corazon Aquino has prompted various namings of public landmarks and creations of memorials. Among these are as follows:

In 2018, she was recognized by the Human Rights Victims Claims Board as a motu proprio human rights violations victim of the Ferdinand Marcos martial law era.[125]