Xi Jinping

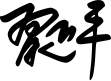

Xi Jinping (/ˈʃiː dʒɪnˈpɪŋ/, or often /ˈʒiː/; Chinese: 习近平; pinyin: Xí Jìnpíng, pronounced [ɕǐ tɕîn.pʰǐŋ];[a] born 15 June 1953) is a Chinese politician who has been the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), and thus the paramount leader of China, since 2012. Xi has also been the president of the People's Republic of China (PRC) since 2013. As a member of the fifth generation of Chinese leadership, Xi is the first CCP general secretary born after the establishment of the PRC.

In this article, the surname is Xí (习).

Xi Jinping

- Li Keqiang (2013–23)

- Li Qiang (since 2023)

- Li Yuanchao (2013–18)

- Wang Qishan (2018–23)

- Han Zheng (since 2023)

Hu Jintao

Hu Jintao

15 June 1953

Beijing, China

CCP (since 1974)

- Xi Zhongxun (father)

- Qi Xin (mother)

Qi Qiaoqiao (sister)

Liu Meixun

习近平

習近平

Xí Jìnpíng

Xí Jìnpíng

ㄒㄧˊ ㄐㄧㄣˋ ㄆㄧㄥˊ

Hsi2 Chin4-p῾ing2

Sí Jìn-píng

Shí Jìn-píng

Zih⁸ Jin⁶-bin⁶

Sip6 Kiun4 Pin2[1]

Si̍p Khiun-phìn

Jaahp Gahn-pìhng

Zaap6 Gan6-ping4

Si̍p Kīn-pêng

Si̍p Kīn-pîng

Síp Gîn-bíng

Sĭk Gê̤ṳng-ping

The son of Chinese Communist veteran Xi Zhongxun, Xi was exiled to rural Yanchuan County as a teenager following his father's purge during the Cultural Revolution. He lived in a yaodong in the village of Liangjiahe, Shaanxi province, where he joined the CCP after several failed attempts and worked as the local party secretary. After studying chemical engineering at Tsinghua University as a worker-peasant-soldier student, Xi rose through the ranks politically in China's coastal provinces. Xi was governor of Fujian from 1999 to 2002, before becoming governor and party secretary of neighboring Zhejiang from 2002 to 2007. Following the dismissal of the party secretary of Shanghai, Chen Liangyu, Xi was transferred to replace him for a brief period in 2007. He subsequently joined the Politburo Standing Committee (PSC) of the CCP the same year and was the first-ranking secretary of the Central Secretariat in October 2007. In 2008, he was designated as Hu Jintao's presumed successor as paramount leader. Towards this end, Xi was appointed vice president of the PRC and vice chairman of the CMC. He officially received the title of leadership core from the CCP in 2016.

While overseeing China's domestic policy, Xi has introduced far-ranging measures to enforce party discipline and strengthen internal unity. His anti-corruption campaign led to the downfall of prominent incumbent and retired CCP officials, including former PSC member Zhou Yongkang. For the sake of promoting "common prosperity", Xi has enacted a series of policies designed to increase equality, overseen targeted poverty alleviation programs, and directed a broad crackdown in 2021 against the tech and tutoring sectors. Furthermore, he has expanded support for state-owned enterprises (SOEs), advanced military-civil fusion, and attempted to reform China's property sector. Following the onset of COVID-19 pandemic in mainland China, he initially presided over a zero-COVID policy from January 2020 to December 2022 before ultimately shifting towards a mitigation strategy.

Xi has pursued a more aggressive foreign policy, particularly with regard to China's relations with the U.S., the nine-dash line in the South China Sea, and the Sino-Indian border dispute. Additionally, for the sake of advancing Chinese economic interests abroad, Xi has sought to expand China's influence in Africa and Eurasia by championing the Belt and Road Initiative. Despite meeting with Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou in 2015, Xi presided over a deterioration in relations between Beijing and Taipei under Ma's successor, Tsai Ing-wen. In 2020, Xi oversaw the passage of a national security law in Hong Kong which clamped down on political opposition in the city, especially pro-democracy activists.

Often described as a dictator by political and academic observers, Xi's tenure has included an increase of censorship and mass surveillance, deterioration in human rights, including the internment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, a cult of personality developing around Xi, and the removal of term limits for the presidency in 2018. Xi's political ideas and principles, known as Xi Jinping Thought, have been incorporated into the party and national constitutions. As the central figure of the fifth generation of leadership of the PRC, Xi has centralized institutional power by taking on multiple positions, including new CCP committees on national security, economic and social reforms, military restructuring and modernization, and the Internet. In October 2022, Xi secured a third term as CCP General Secretary, and was reelected state president for a third term in March 2023.

Early life and education

Xi Jinping was born in Beijing on 15 June 1953,[2] the third child of Xi Zhongxun and his second wife Qi Xin. After the founding of the PRC in 1949, Xi's father held a series of posts, including Party propaganda chief, vice-premier, and vice chairperson of the National People's Congress.[3] Xi had two older sisters, Qiaoqiao, born in 1949 and An'an (安安; Ān'ān), born in 1952.[4][5] Xi's father was from Fuping County, Shaanxi.[6]

Xi went to the Beijing Bayi School,[7][8] and then the Beijing No. 25 School,[9] in the 1960s. He became friends with Liu He, who attended Beijing No. 101 School in the same district, and who later became China's vice premier and a close advisor to Xi after he became China's paramount leader.[10][11] In 1963, when he was aged 10, his father was purged from the CCP and sent to work in a factory in Luoyang, Henan.[12] In May 1966, the Cultural Revolution cut short Xi's secondary education when all secondary classes were halted for students to criticise and fight their teachers. Student militants ransacked the Xi family home and one of Xi's sisters, Xi Heping, "was persecuted to death."[13][14]

Later, his mother was forced to publicly denounce his father, as he was paraded before a crowd as an enemy of the revolution. His father was later imprisoned in 1968 when Xi was aged 15. Without the protection of his father, Xi was sent to work in Liangjiahe Village, Wen'anyi, Yanchuan County, Yan'an, Shaanxi, in 1969 in Mao Zedong's Down to the Countryside Movement.[15] He worked as the party secretary of Liangjiahe, where he lived in a cave house.[16] According to people who knew him, this experience led him to feel affinity with the rural poor.[17] After a few months, unable to stand rural life, he ran away to Beijing. He was arrested during a crackdown on deserters from the countryside and sent to a work camp to dig ditches, but he later returned to the village. He then spent a total of seven years there.[18][19]

The misfortunes and suffering of his family in his early years hardened Xi's view of politics. During an interview in 2000, he said, "People who have little contact with power, who are far from it, always see these things as mysterious and novel. But what I see is not just the superficial things: the power, the flowers, the glory, the applause. I see the bullpens and how people can blow hot and cold. I understand politics on a deeper level." The "bullpens" (牛棚) was a reference to Red Guards' detention houses during the Cultural Revolution.[17]

After seven rejections, Xi joined the Communist Youth League of China in 1971 on his eighth attempt after he befriended a local official.[8] He reunited with his father in 1972, because of a family reunion ordered by premier Zhou Enlai.[14] From 1973, he applied to join the CCP ten times and was finally accepted on his tenth attempt in 1974.[20][21][22] From 1975 to 1979, Xi studied chemical engineering at Tsinghua University as a worker-peasant-soldier student in Beijing. The engineering majors there spent about 15 percent of their time studying Marxism–Leninism and 5 percent of their time doing farm work and "learning from the People's Liberation Army."[23]

Early political career

From 1979 to 1982, Xi was secretary for his father's former subordinate Geng Biao, the vice premier and secretary-general of the CMC.[8] In 1982, he was sent to Zhengding County in Hebei as deputy party secretary of Zhengding County. He was promoted in 1983 to secretary, becoming the top official of the county.[24] Xi subsequently served in four provinces during his regional political career: Hebei (1982–1985), Fujian (1985–2002), Zhejiang (2002–2007), and Shanghai (2007).[25] Xi held posts in the Fuzhou Municipal Party Committee and became the president of the Party School in Fuzhou in 1990. In 1997, he was named an alternate member of the 15th Central Committee of the CCP. However, of the 151 alternate members of the Central Committee elected at the 15th Party Congress, Xi received the lowest number of votes in favour, placing him last in the rankings of members, ostensibly due to his status as a princeling.[b][26]

From 1998 to 2002, Xi studied Marxist theory and ideological education in Tsinghua University,[27] graduating with a doctorate in law and ideology in 2002.[28] In 1999, he was promoted to the office of Vice Governor of Fujian, and became governor a year later. In Fujian, Xi made efforts to attract investment from Taiwan and to strengthen the private sector of the provincial economy.[29] In February 2000, he and then-provincial party secretary Chen Mingyi were called before the top members of PSC – general secretary Jiang Zemin, premier Zhu Rongji, vice president Hu Jintao and Discipline Inspection secretary Wei Jianxing – to explain aspects of the Yuanhua scandal.[30]

In 2002, Xi left Fujian and took up leading political positions in neighbouring Zhejiang. He eventually took over as provincial Party Committee secretary after several months as acting governor, occupying a top provincial office for the first time in his career. In 2002, he was elected a full member of the 16th Central Committee, marking his ascension to the national stage. While in Zhejiang, Xi presided over reported growth rates averaging 14% per year.[31] His career in Zhejiang was marked by a tough and straightforward stance against corrupt officials. This earned him a name in the national media and drew the attention of China's top leaders.[32] Between 2004 and 2007, Li Qiang acted as Xi's chief of staff through his position as secretary-general of the Zhejiang Party Committee, where they developed close mutual ties.[33]

Following the dismissal of Shanghai Party secretary Chen Liangyu in September 2006 due to a social security fund scandal, Xi was transferred to Shanghai in March 2007, where he was the party secretary there for seven months.[34][35] In Shanghai, Xi avoided controversy and was known for strictly observing party discipline. For example, Shanghai administrators attempted to earn favour with him by arranging a special train to shuttle him between Shanghai and Hangzhou for him to complete handing off his work to his successor as Zhejiang party secretary Zhao Hongzhu. However, Xi reportedly refused to take the train, citing a loosely enforced party regulation that stipulated that special trains can only be reserved for "national leaders."[36] While in Shanghai, he worked on preserving unity of the local party organisation. He pledged there would be no 'purges' during his administration, despite the fact many local officials were thought to have been implicated in the Chen Liangyu corruption scandal.[37] On most issues, Xi largely echoed the line of the central leadership.[38]

Public life

It is hard to gauge the opinion of the Chinese public on Xi, as no independent surveys exist in China and social media is heavily censored.[394] However, he is believed to be widely popular in the country.[395][396] According to a 2014 poll co-sponsored by the Harvard Kennedy School's Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Xi ranked 9 out of 10 in domestic approval ratings.[397] A YouGov poll released in July 2019 found that about 22% of people in mainland China list Xi as the person they admire the most, a plurality, although this figure was less than 5% for residents of Hong Kong.[398] In the spring of 2019, the Pew Research Center made a survey on confidence on Xi Jinping among six-country medians based on Australia, India, Indonesia, Japan, Philippines and South Korea, which indicated that a median 29% have confidence in Xi Jinping to do the right thing regarding world affairs, meanwhile a median of 45% have no confidence; these numbers are slightly higher than those of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un (23% confidence, 53% no confidence).[399] A poll by Politico and Morning Consult in 2021 found that 5% of Americans have a favorable opinion of Xi, 38% unfavorable, 17% no opinion and 40%, a plurality, never hearing of him.[400]

In 2017, The Economist named him the most powerful person in the world.[401] In 2018, Forbes ranked him as the most powerful and influential person in the world, replacing Russian President Vladimir Putin, who had been ranked so for five consecutive years.[402] Since 2013, Reporters Without Borders, an international non-profit and non-governmental organization with the stated aim of safeguarding the right to freedom of information, included Xi among the list of press freedom predators.[403]

Unlike previous Chinese leaders, Chinese state media has given a more encompassing view of Xi's private life, although still strictly controlled. According to Xinhua News Agency, Xi would swim one kilometer and walk every day as long as there was time, and is interested in foreign writers, especially Russian.[323] Some of his favorite foreign authors include Leo Tolstoy, Mikhail Sholokhov,[404] Victor Hugo, Honoré de Balzac, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Jack London.[405] Xi is reported to also like films and TV shows such as Saving Private Ryan,[406] Sleepless in Seattle, The Godfather[407] and Game of Thrones,[408] and he has praised Chinese independent film-maker Jia Zhangke.[409] The Chinese state media has also cast him as a fatherly figure and a man of the people, determined to stand up for Chinese interests.[321]